Summary:

– Iceland was one of the countries most affected by the 2008 financial crisis.

– In mid-August, the Ministry of Finance announced the gradual lifting of capital controls put in place in 2008.

– Early general elections could create uncertainty for investors.

After being severely affected by the 2008 financial crisis, Iceland is now in the process of gradually lifting the capital controls put in place almost eight years ago. This lifting could pose a risk to the country, especially as the uncertain outcome of the general elections on October 29 could cause some investors to take a more wait-and-see approach to the country’s situation.

The onset of the crisis

Iceland was severely affected by the 2008 crisis. After growing by an average of 5% per year between 1996 and 2007, GDP fell by 4.7% in 2009 and then by 3.6% in 2010. Iceland was one of the first countries to be affected by the financial crisis due to the extremely rapid development of its own financial sector. Privatized in the early 2000s, Icelandic banks, constrained by the small size of their domestic market, sought to expand outside Iceland. Access to the European Economic Area (EEA) enabled them to grow rapidly by opening subsidiaries abroad (the European « passport » system) and acquiring other financial companies. The high-yield investments offered by Icelandic banks also explain the strong attraction for investors.

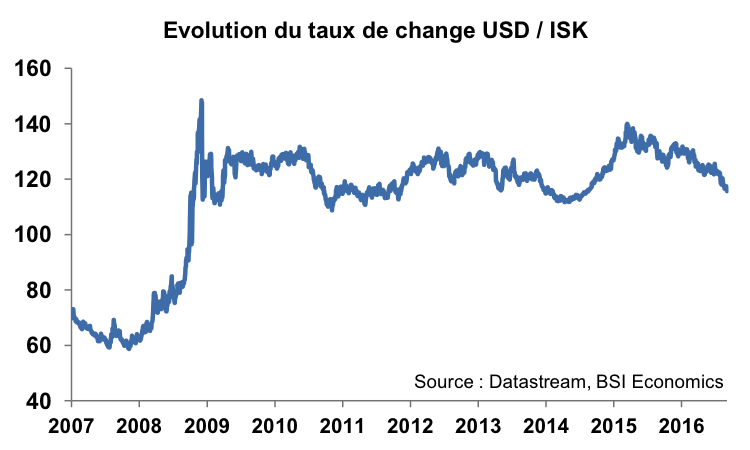

Icelandic banking assets thus represented 900% of GDP at the end of 2007, compared with 100% in 2004. In total, the banking sector accounted for 10% of Iceland’s GDP in 2007, three times more than in 1997. The country’s three main banks—Kaupthing, Glitnir, and Landsbanki—accounted for 85% of total assets at the time. When the crisis hit, these three banks were unable to refinance themselves due to the markets’ reluctance to do so, or only at exorbitant rates. The state therefore nationalized these banks and decided to guarantee Icelanders’ deposits in Icelandic banks. It also introduced capital controls on outflows in November 2008 to stabilize the Icelandic krona after the currency lost half its value due to massive capital flight.

The plan to lift capital controls

In mid-August 2016, the Icelandic Ministry of Finance announced the gradual lifting of almost all capital control restrictions. Several restrictions will be lifted as soon as the bill is passed by Parliament, notably those relating to households and foreign direct investment (FDI) flows. Other measures will be lifted as of January 1, 2017 (increase in the ceiling on foreign currency investments, etc.).

According to estimates by the Ministry of Finance, the lifting of capital controls could lead to an outflow of capital of around ISK 40 billion (€0.3 billion, or 2% of GDP) as soon as the law is passed, and ISK 165 billion (€1.2 billion, or 8% of GDP) in the second stage.

Several factors mitigate the risk associated with lifting capital controls

The main risk facing Iceland in the short term is the risk associated with the lifting of capital controls. This could lead to a massive outflow of capital (as mentioned above), which would have repercussions through several channels: a fall in the exchange rate, an increase in inflation, etc. However, at least five factors mitigate this risk:

– A series of auctions has been held since 2011 (with a 38% discount) to reduce the amount of liquid assets held by non-resident investors still blocked in Iceland. The discounted auction allows investors who wish to do so to withdraw their assets from the country, but at a less favorable rate than the current rate. Following the last auction, ISK 250 billion (EUR 1.9 billion, or 12% of GDP) was still frozen in Iceland at the beginning of July. This is still a significant amount, but much lower than in 2008 when capital controls were introduced. At that time, liquid assets held by non-resident investors and frozen represented 40% of GDP. This strategy has therefore minimized the risk of capital flight, which could undermine economic and financial stability.

– Foreign exchange reserves are at a comfortable level, equivalent to seven months of imports. The Central Bank will be able to intervene if necessary in the event of a foreign exchange shock (in the event of a massive outflow of capital). ο Supervision of the banking sector has improved significantly. Banks are well capitalized (Landsbanki is publicly owned, although privatization is under consideration) and profitable. Financing is mainly through deposits, which provides banks with a comfortable margin.

– High interest rates in Iceland allow certain investors to engage in carry trade, i.e., borrowing capital in countries with low interest rates (such as the eurozone or the Nordic countries) and investing it in countries with high interest rates (such as Iceland).

– Iceland has now returned to economic health. Its GDP grew by 4% in 2015 (almost twice that of the eurozone), unemployment reached 2.6% in June 2016, and public finances have been consolidated, with public debt falling from 95% of GDP in 2011 to 68% of GDP in 2015 (and expected to be 56% of GDP in 2016). Moody’s recently upgraded Iceland’s sovereign rating by one notch to A3, while S&P and Fitch maintained their ratings with a stable outlook. The economy has also significantly developed its tourism sector, which serves as a growth driver for the banking sector. The country’s economic health and reduced exposure to the financial sector could reassure investors about its more robust economic fundamentals, providing an additional guarantee against a massive outflow of capital despite the lifting of capital controls. These last two factors (high interest rates and economic health) partly explain the krona’s appreciation against the dollar since 2015 (+17%).

Investors adopting a wait-and-see approach

However, the government has also announced that early elections—following the forced resignation of the former prime minister implicated in the Panama Papers scandal—will be held on October 29. Uncertainty remains as to whether an alliance will be formed if the current coalition does not win the elections, as some polls suggest. Parliament could therefore be more fragmented than usual. The political situation could therefore be perceived as a risk for investors, who may adopt a wait-and-see approach. This could be further amplified by the lifting of capital controls.

Conclusion

The lifting of capital controls could lead to a significant capital flight (estimated at between 2% and 8% of GDP). The uncertain outcome of the October general election could prompt some investors to adopt a wait-and-see approach, which would amplify the capital outflow process. However, the series of auctions, foreign exchange reserves, banking supervision, interest rate levels, and the healthy state of the economy mitigate the risk associated with the lifting of capital controls.