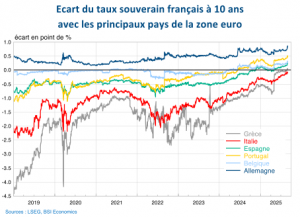

This note proposes to decipher a striking chart related to current economic events. This Killer Chart highlights the unfavorable trend in French 10-year sovereign bond yields compared to those of its main European partners. The hierarchy of sovereign rates in the eurozone is being reshaped to the detriment of French debt. Despite the weight of its economy, the marked deterioration in public finances now leads France to be perceived, in terms of credit quality, as a peripheral country in the eurozone.

Download the PDF: killer-chart-french-debt-in-investors-crosshairs

Why is this interesting?

Following François Bayrou’s decision to put his government’s responsibility to the test with a confidence vote on September 8, and with social protests planned for September 10, France is entering a new phase of political turmoil. Given that several parties have already announced their refusal to grant confidence, the fall of the government appears to be a very likely scenario.

This instability comes at a time when the public deficit has reached -5.8% of GDP in 2024, the highest level in the eurozone. The financial markets are expressing concern about the trajectory of French public finances, especially since more than half of the government’s debt securities are held by non-residents (54.7% of the total). These foreign investors’ lack of knowledge of our institutional system could increase the risk of panic reactions, unlike domestic creditors who are more familiar with constitutional mechanisms.

In this climate, French 10-year sovereign rates are rising, while our European partners are showing greater stability. Since the dissolution of June 2024, spreads[1] have widened and the hierarchy of sovereign rates in the euro zone has been shaken up: Spain, Belgium, and Portugal have started borrowing at lower costs than France. The spread with Italy has now narrowed to less than 10 basis points (0.1%), a situation unprecedented since the introduction of the euro. If France were to borrow at a higher cost than Italy, the signal sent to the markets would be worrying.

It should also be noted that France now borrows at a higher cost than Greece on 10-year bonds. However, this comparison must be qualified: Greek debt is still largely held by public creditors and the proportion of securities that are actually tradable on the markets remains low. The Greek rate is therefore not fully representative of a true market rate and skews comparisons.

What should we make of this?

While we should not overinterpret France’s relative downgrading in the European sovereign bond hierarchy, it is nevertheless important to ask ourselves: what crisis does this signal?

What is at stake is the sustainability of French public debt. This is defined as a country’s ability to meet its repayment obligations without compromising macroeconomic and financial stability.

With this in mind, a key determinant of sustainability is the credibility of economic policy. However, the succession of political crises in France has seriously undermined this credibility. Yet the confidence of financial markets is essential: if it erodes, investors will demand higher interest rates, which will increase the cost of debt, further deteriorate public finances, and increase the risk of unsustainability.

The recent trend in interest charges provides a clear illustration of this. Interest charges represented 2% of GDP in 2024 (€59 billion) and are expected to reach 2.2% in 2025 (€67 billion) according to the government’s Medium-Term Structural Plan (PSMT), climbing to 3.2% of GDP in 2029 (€108 billion). In other words, France is entering a phase in which the cost of servicing its debt will absorb an increasing share of public resources, triggering a vicious circle of debt and fiscal fragility.

It should also be borne in mind that sustainability depends less on the level of debt at a given moment than on its dynamics, i.e., its trajectory over time and the ability to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio. Two factors are decisive:

- The primary budget balance: this measures the difference between revenue and expenditure excluding interest. This is precisely France’s weakness. With a primary deficit of -3.8% of GDP in 2024, the highest in the eurozone, debt can only increase in the absence of correction. Reducing this deficit requires structural reforms: public spending tends to grow spontaneously by +1.4% to +1.6% per year in volume, while potential growth is estimated at between +1% and +1.2%. This divergence could prove explosive in the medium term.

- The « snowball » effect: this depends on the relationship between the average interest rate on debt (r) and nominal GDP growth (g). If g > r, the relative weight of debt automatically decreases. Conversely, if r > g, debt grows on its own, even with a balanced budget. Since 2017 (excluding 2020), France has benefited from a favorable r-g differential. But this is fading: interest rates are rising while nominal growth is slowing. The apparent interest rate on debt is now converging towards the GDP growth rate in value terms. With public debt exceeding 100% of GDP, this means that France is approaching a self-perpetuating debt dynamic, where the weight of debt increases solely as a result of interest charges. In other words, debt refinancing may soon come at a marginal cost that is much higher than growth, triggering a worrying snowball effect.

This brief analysis of the sustainability of French public finances highlights the explosive nature of debt in the absence of structural reforms. In this context, the adoption of austerity measures does not appear to be a comfortable choice, but a necessity to avoid lasting divergence and the risk of a debt crisis.

It should be remembered that France is already subject to an excessive deficit procedure by the European Commission. If the recovery trajectory were to be called into question, the Council could impose sanctions, including a fine of up to 0.05% of the previous year’s GDP.

A key factor to watch now is the judgment of the rating agencies, whose decisions could precipitate a shock to French debt. An important deadline is approaching: Fitch is due to publish its next assessment on September 12, four days after the confidence vote. Having already downgraded the rating to AA- and maintained a negative outlook, the agency could go further and downgrade French sovereign debt to A+ in the event of a major political crisis, such as the fall of the Bayrou government.

Such a downgrade would have direct implications for the financial sector. Under Basel III/CRR III banking regulations, the change in France’s rating from AA- to A+ would alter the risk category of sovereign exposures, with the weighting increasing from 30% to 50%. This would represent a 67% increase in risk-weighted assets (RWA) linked to French government bonds, and therefore a proportional increase in regulatory capital requirements (CET1 ratio). Such a move would also increase capital requirements under Solvency II, via the widening of sovereign spreads and their impact on value-at-risk (VA).

[1] A spread represents the difference in yield between bonds, in this case from different countries with similar maturities. A positive (or negative) spread therefore corresponds to a situation where the risk premium tends to increase (or decrease).