Summary:

- During the Covid-19 pandemic, international trade declined significantly in 2020.

- While one might have thought that the economies most dependent on exports (Asia and Europe in particular) would be the hardest hit by this sudden halt in trade, the opposite actually happened.

- This paradox can be explained by the high degree of diversification of European and Asian economies in terms of sectors of activity and trading partners. During 2020, the economies with the most diversified exports were those that recorded the smallest declines in export revenues.

- Conversely, economies with highly specialized exports, particularly in the raw materials sector, were particularly affected by the decline in trade volumes and prices for these products.

Economists generally view openness to international trade as an effective means of boosting a country’s development. The most frequently cited example is that of the « Asian dragons » (South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan), which in the 1970s and 1980s relied heavily on export revenues to finance private and public investment in order to kick-start a new phase of development. However, this integration into global trade is not without risk. It exposes exporting countries to potential external shocks that can have a direct impact on growth.

In 2020, the world had to learn to live with the coronavirus and multiple health restrictions. The economic consequences of this pandemic have been significant for international trade. Indeed, all major regions of the world faced a decline in export revenues in 2020. Nevertheless, this negative impact was not uniform in magnitude across regions.

To explain these differences between the world’s major geographical areas, three risk factors are examined in this note: (i) dependence on exports, (ii) the degree of sectoral concentration of exports, and (iii) the degree of concentration of export destinations. We will see that it is the latter two factors that mainly explain this differentiated impact of the decline in global trade on economic growth.

1) A global trade crisis with varying effects

1.1 The fall in global trade in 2020

As the Covid-19 pandemic began to spread across the globe in early 2020, many countries around the world imposed social distancing measures and even lockdowns to slow the spread of the virus.

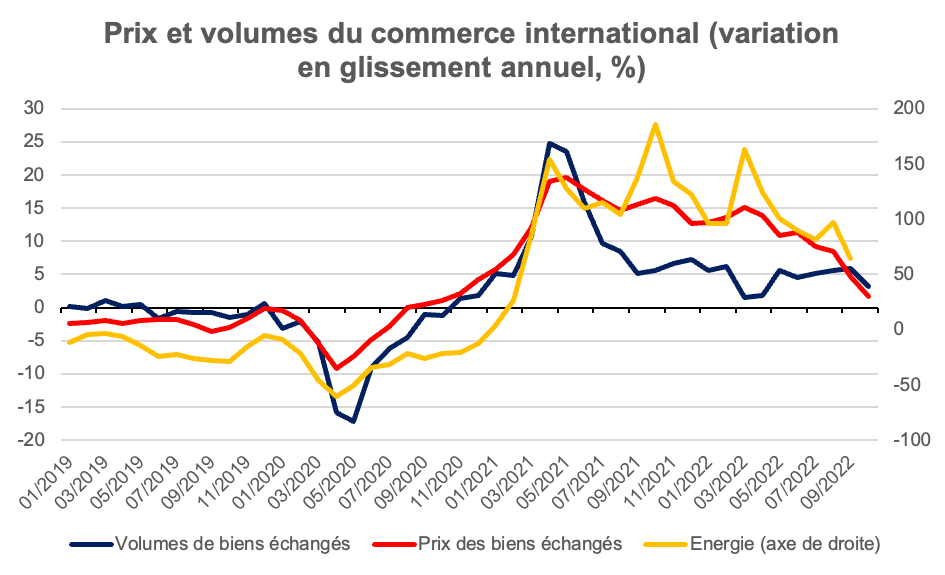

Figure 1

Sources: CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis

On the demand side, these measures mainly limited economic agents’ ability to consume and invest. On the supply side, they reduced the available labor force by forcing workers to stay at home and also created significant logistical disruptions in global value chains. As shown in Chart 1 above, the combination of these supply and demand dynamics contributed to a sharp decline in the quantities of goods and services traded during 2020 (approximately -17% in June 2020 compared to June 2019). On the other hand, the prices of goods and services traded also fell over the same period, although to a lesser extent than the quantities. This fall in prices seems to be explained in particular by the drop in energy prices, which was around six times greater than that of all traded products.

1.2 Differentiated effects around the world

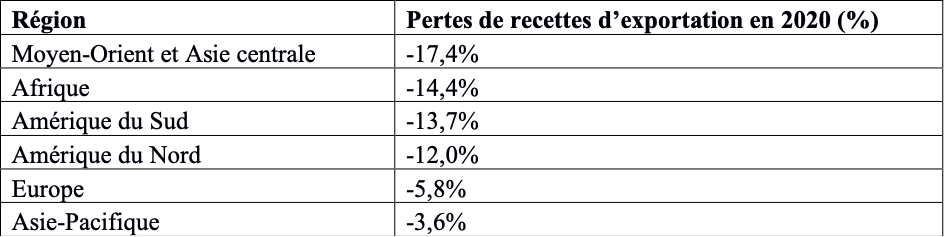

Although the shock of the coronavirus pandemic has affected global trade as a whole, it has not had a uniform impact on revenues from foreign sales of goods (export revenues) in different regions of the world, as shown in Table A below. The economic zone that suffered the greatest loss of export revenue due to the decline in global trade was the Middle East and Central Asia, followed by Africa, South America, and North America. Europe and Asia-Pacific experienced a much more moderate decline in revenue than the rest of the world.

Table A

Sources: International Trade Analysis Database (CEPII), author’s calculations

How can we explain these differences in the impact of the slowdown in international trade on export revenues across regions? To beginwith , it is interesting to consider the concept of export dependency.

2) Export dependency

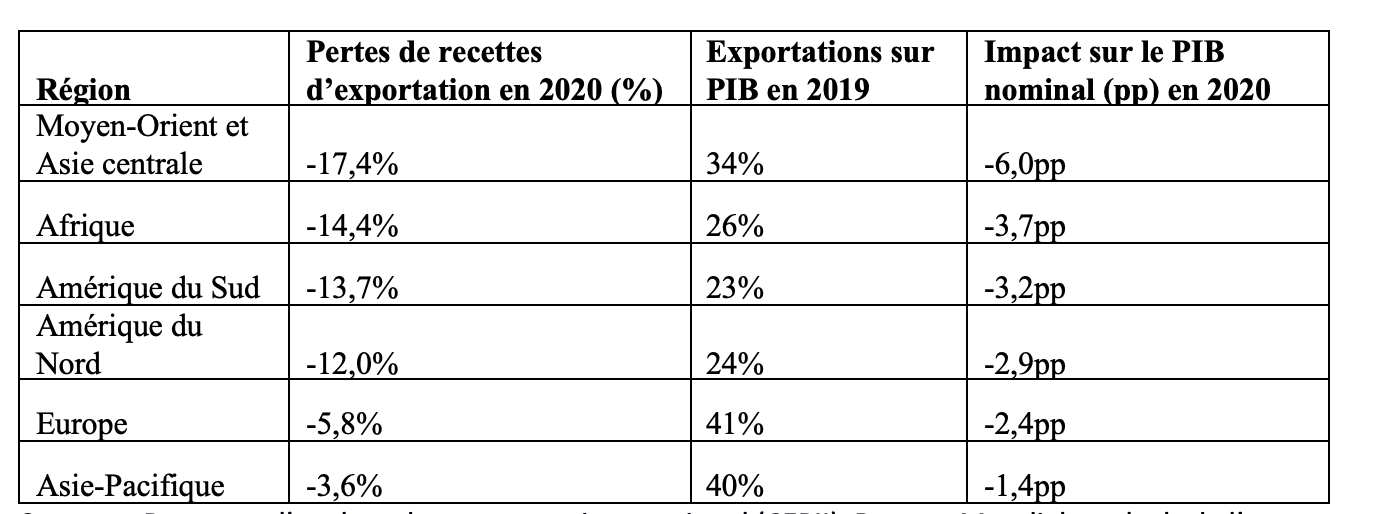

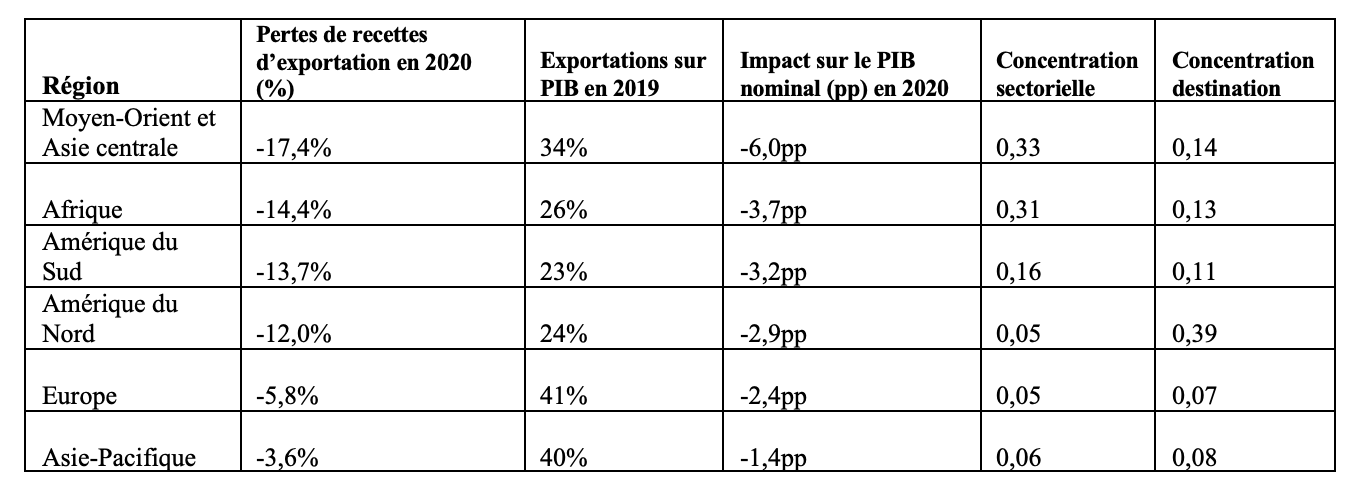

Export dependency here refers to the share of exports in GDP. According to this definition, the higher this share, the more dependent a country’s economy is on exports. It would seem logical that these countries would be relatively more affected than others by an external shock that would bring global trade to a sudden halt. Table B below shows the ratio of exports to GDP (in value terms). The impact of the loss of export revenues translated into GDP points is also shown in the last column.

Table B

Sources: Basis for the analysis of international trade (CEPII), World Bank, author’s calculations

The conclusions offered by this table may seem surprising. It turns out that the regions of the world most dependent on exports, namely Europe and Asia-Pacific, are not the ones that have been most affected by the Covid-19 shock. The main reason behind these counterintuitive results is that the degree of export dependence appears to be a poor predictor of the magnitude of export revenue losses in the event of an external shock. In the case of Asia-Pacific, the rapid rebound in exports in China and Vietnam in the healthcare and electronics sectors has offset more pronounced declines in exports in the Indian subcontinent (India, Bangladesh). In Europe, the industrial bloc comprising Germany and the countries of Central Europe showed strong resilience during the year thanks to sustained export levels in the medical and household equipment sectors. Conversely, France, Italy, and the United Kingdom suffered more due to their specialization in the transport manufacturing (automotive and aeronautics) and textile industries. This effect could be related to specialization, meaning that some elements are missing from the analysis to fully understand the available data. In order to resolve the paradox observed in Table B, we must now turn our attention to the concept of export concentration.

3. The essential role of export concentration

3.1 Sectoral concentration and concentration of import destinations

Sectoral concentration of exports can be defined as the degree to which a country concentrates its exports on a small number of products/sectors of activity. A well-known example of high sectoral concentration is that of the Gulf oil states, where a large proportion of trade revenues (and a large proportion of revenues in general) come almost exclusively from the sale of hydrocarbons.

There are numerous economic studies[1] dealing with the risks faced by countries that are dependent on the sale of one or a few products abroad. First, a country with highly concentrated exports is particularly vulnerable to fluctuations in demand and prices in the relevant market(s). This is especially true when the exported products are food or energy commodities traded on global markets, for which revenues are volatile and tend to be closely aligned with the global economic cycle.

Furthermore, specialization in raw material exports tends to make export diversification more difficult in the future (an effect known as « Dutch disease »). This is because the appreciation of the local currency caused by revenues from commodity sales would reduce the competitiveness of other sectors of the economy. These sectors would then find themselves unable to attract foreign buyers and would have no incentive to make the investments necessary to achieve productivity gains.

It should be noted that concentration does not only concern exported products but also the recipients of exports. A country may export a wide range of goods and services but to a single importer, which also constitutes a source of risk. Indeed, a country that exports to only one or very few partners finds itself particularly dependent on the domestic economic situation of its partner(s).

3.2 Export concentration as a crucial explanatory factor

Table C below combines the data presented in Tables A and B, adding measures of sectoral concentration and export destination for the main regions of the world. Concentration measures are expressed as a normalized index from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating maximum concentration. The results obtained shed considerable light on the paradox observed in the previous section.

Table C

Sources: International Trade Analysis Database (CEPII), World Bank, author’s calculations

On the subject of sectoral concentration, Table C shows a clear separation between the Middle East, Africa, and South America on the one hand, and North America, Europe, and Asia-Pacific on the other. The first group, mainly composed of emerging and developing countries, has relatively high levels of sectoral concentration (although less so for Latin America), while the second group, composed of most advanced economies, shows clear export diversification. This two-part division based on the level of sectoral concentration and economic development is also visible in the impact of the negative trade shock of 2020 on economic growth. The three regions with the most concentrated exports are those that have suffered the most from the Covid-19 shock, due to the significant drop in the volumes and prices of these products.

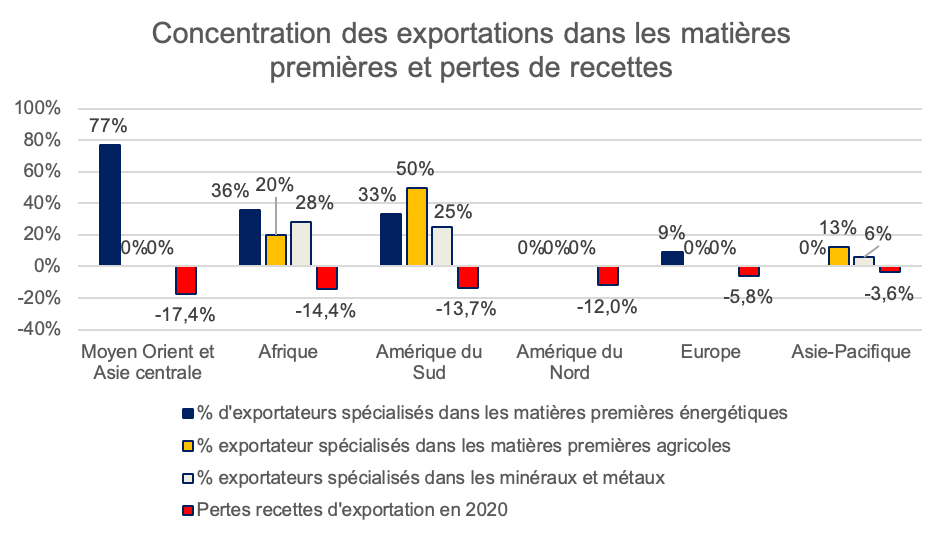

As shown in Figure 2, the share of countries with exports concentrated in raw materials by region appears to be a much better indicator for anticipating export revenue losses during a Covid-19-type shock than the degree of export dependence. More specifically, it appears that the share of exporters specializing in the sale of energy commodities (coal, oil, gas, electricity) closely mirrors the distribution of export revenue losses recorded by region of the world in 2020. The price effect was particularly high for these energy exporters. This can be explained in particular by a fall in demand in industrial sectors that have come to a standstill, as well as by the disappearance of transport travel in a global context of lockdown. Added to this is the inability of the main producing countries to organize a coordinated reduction in production quantities.

Figure 2

Sources: UNCTAD, Base for International Trade Analysis (CEPII), author’s calculations

Nevertheless, the level of sectoral concentration does little to explain the sharp decline in export revenues in North America relative to Asia-Pacific and Europe. This phenomenon is certainly better explained by the high concentration of export destinations in this region.

North America is made up of three main hubs linked by close but unbalanced trade relations. Canada and Mexico are highly dependent on the United States, which buys about three-quarters of their respective exports. Conversely, US exports are not significantly concentrated on any particular destination. In addition, Canada (26% of GDP in 2019) and Mexico (37%) have a much higher export dependency ratio than the United States (8%). It is therefore clear that the slowdown in US demand during 2020 had a substantial impact on its two main neighbors, which saw their export revenues and growth particularly affected.

Conclusion

The analysis carried out in this paper shows that it is primarily the regions with the most concentrated exports in raw materials (particularly energy) that have been most affected by the trade frictions caused by the pandemic.

Paradoxically, the geographical areas most dependent on exports suffered less from the shock because they were highly diversified in terms of the products sold and trading partners. It would appear that reducing the sectoral concentration of exports is a possible way for a number of emerging and developing countries to cushion the impact of global recessions, which cause a decline in trade volumes and prices.

To achieve this, various strategies are possible, as shown by the example of the Gulf countries. Some states, such as Qatar, have opted for a strategy of « vertical diversification, » maintaining their specialization in energy while integrating new downstream skills (petrochemicals, ethylene production). Conversely, others, such as the United Arab Emirates, have opted for « horizontal diversification » by opening up more to new activities that are more service-oriented, such as tourism and recreation, or air transport.

Sources

Articles

Bahar, Dany, and Miguel Santos (2016). “One More Resource Curse: Dutch Disease and Export Concentration.” CID Research Fellow and Graduate Student Working Paper Series 2016.68, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Jansen, Marion (2004): Income volatility in small and developing economies: export concentration matters, WTO Discussion Paper, No. 3, World Trade Organization (WTO), Geneva

Data

Basis for international trade analysis, CEPII (documentation available here)

CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis

[1] See in particular Jansen (2004) and Bahar and Santos (2016) – full links at the end of the document.