Abstract:

– The 2008 financial crisis led to increased use of macroprudential tools, particularly in emerging countries. Political economy constraints partly determine how these tools are used.

– Banking lobbies generally oppose new regulatory measures, but certain factors can encourage banks to accept macroprudential policies: localized financial crises that can be addressed by macroprudential tools, transparency, and broad application of measures.

– Political leaders may seek to assign objectives other than financial stability alone to the macroprudential mandate. This is reflected in the objectives explicitly assigned to the macroprudential regulator or in the composition of the governing body of that regulator.

– Certain provisions may help to promote public acceptance of macroprudential policies.

The 2008 financial crisis led to increased use of macroprudential tools in both emerging and advanced countries, as well as to the development of thinking on their application. Macroprudential policies have emerged as a means of ensuring the stability of the financial system despite the existence of economic and financial cycles, in particular by moderating credit growth during boom periods. The operational issues related to the implementation of these tools have therefore recently gained prominence in the literature on the subject (International Monetary Fund, 2013). One of the issues raised in the literature is that of political economy.

Strictly speaking, political economy « seeks to represent the political constraints and decision-making processes » that govern economic policy choices (Bénassy-Quéré et al., 2012 ). This approach examines how political action in the economic sphere can pursue objectives other than the general interest and how the instruments of this action, initially aimed at achieving a social optimum, can be diverted from their original purpose. In the case of macroprudential policy, the aim is to see how political power can subvert its tools to achieve objectives other than financial stability throughout the cycle. Here, we use the concept of political economy in a broad sense. We consider that banks can also hinder the achievement of macroprudential policy objectives through their lobbying of political authorities and thus be a source of political economy problems.

We use original data from a sample of sixteen countries [1]. This work allows us to highlight stylized facts relating to the influence of public and private decision-makers on macroprudential policies.

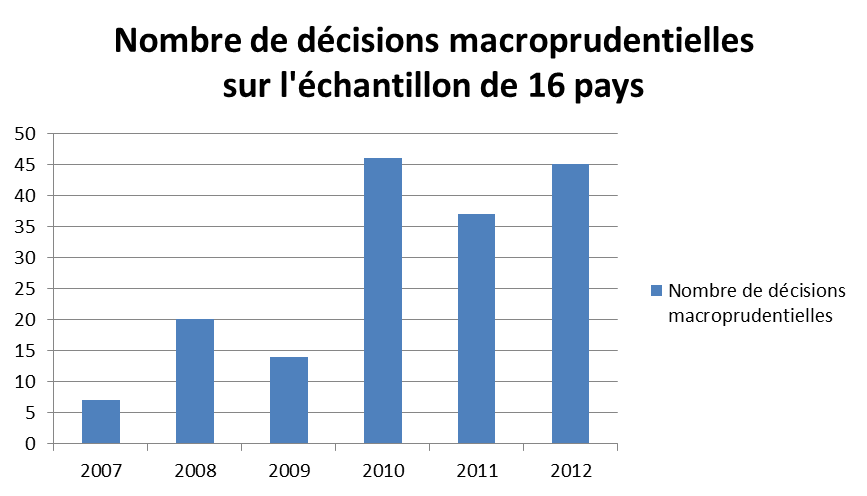

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the number of macroprudential decisions per year for the sample of 16 countries. There was a very sharp increase in the number of measures between 2009 and 2010.

Figure 1: Number of macroprudential decisions per year for the sample of 16 countries.

Source: DG Trésor, BSi Economics

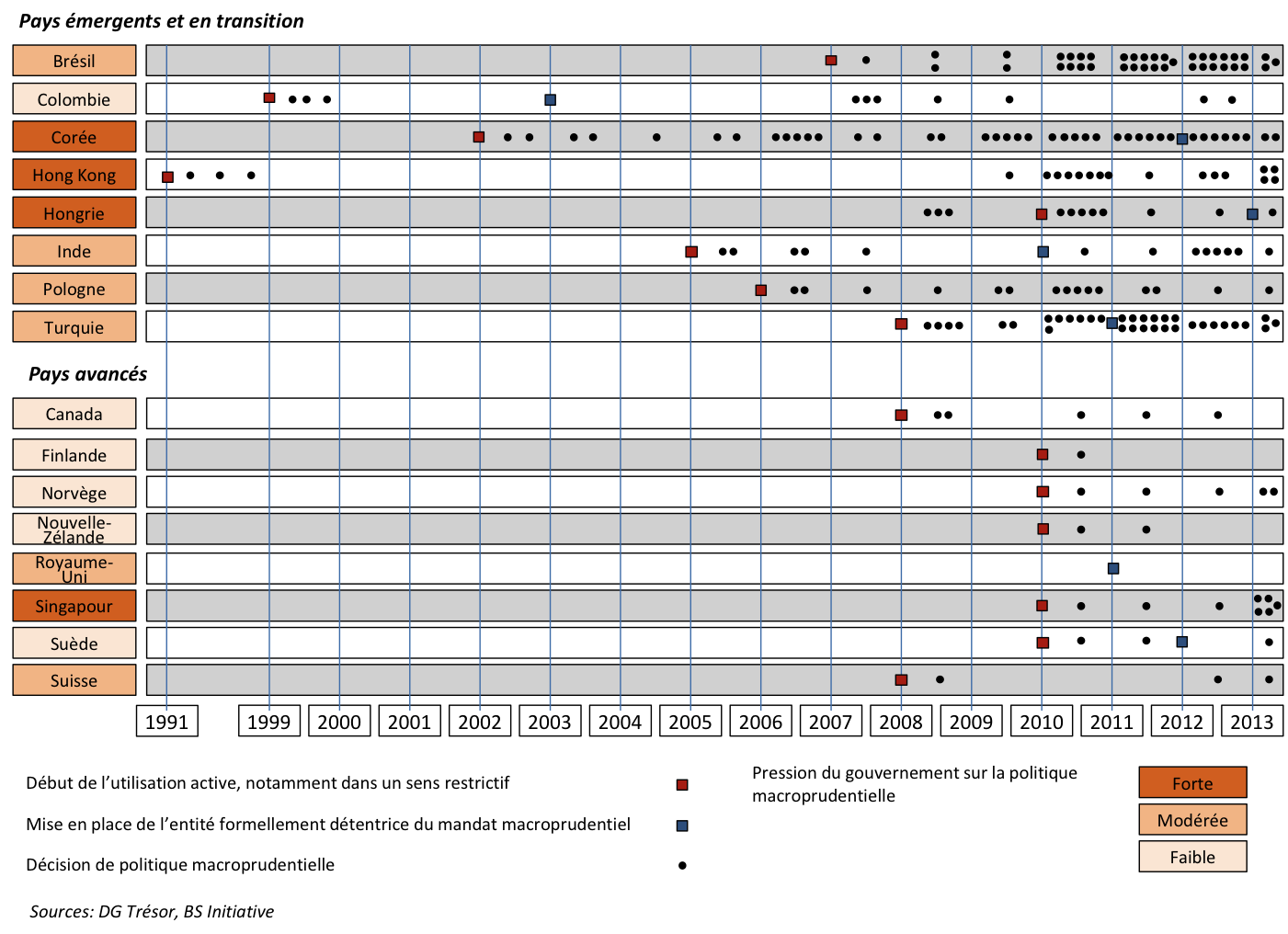

Chart 2 below shows the chronology of individual decisions for each country (each black dot represents a measure) as well as the date of creation of the dedicated macroprudential entity, where one exists. This chart shows that macroprudential policies were used earlier and more frequently in emerging countries than in advanced countries and that since 2010 their use has intensified significantly in all countries in the sample.

Figure 2: Timeline of macroprudential measures in the countries in the sample

1 – Factors determining the level of acceptance of macroprudential policies by banks

Macroprudential policies (MPPs) seem to be more firmly anchored in the regulatory landscape when they originate from a serious financial crisis or a particularly acute episode of financial fragility. In Korea, the memory of the 1997-1998 crisis and the development of the real estate bubble in the early 2000s prompted the Korean authorities to introduce MPPs in the 2000s (limits on the LTV [2] ratio in September 2002 and on the DTI [3] ratio in August 2005) (IMF, 2013a). In Colombia, the strength of the banking sector is largely based on the implementation of significant regulatory measures following the 1998-1999 financial crisis, including macroprudential measures: introduction of limits on LTV and DTI ratios (1999), prohibition on borrowing in foreign currency to lend in local currency, and limits on maturity mismatches for foreign currency loans (Resolution 8 of 2000).

A non-independent monetary policy is likely to increase a country’s interest in macroprudential measures and promote their acceptance by its banking sector. MPCs are, in effect, an additional macroeconomic policy tool for the authorities (IMF, 2013a).In the absence of monetary policy leeway, they may appear to the government and the financial sector as a means of controlling episodes of overheating, especially if certain sectors of the economy are prone to bubble formation.Hong Kong, which does not have an independent monetary policy, was one of the first jurisdictions to introduce MPPs in the early 1990s to guard against real estate bubbles. It is likely that this choice was linked to the territory’s lack of monetary policy independence, with macroprudential policies offering an additional economic steering tool.

The transparency of MPPs is one of the essential conditions for their acceptance by the banking sector. The proliferation of tools is one of the main complaints made by banks against macroprudential policy. In Turkey, between late 2010 and mid-2011, other MPPs (limits on LTV ratios, non-binding credit growth targets, higher risk weights and provisioning for consumer credit) were added to the central bank’s active use of reserve requirements to control credit growth. Banks were highly critical of these macroprudential measures, which they considered unclear and unpredictable. The IMF echoed this view, highlighting the confusion caused by the overlapping of tools (IMF, 2012).

Macroprudential policies can sometimes lead to differences in treatment between banks or between banks and non-bank lenders, and can provoke opposition due to the distortions they create. In Poland, the macroprudential recommendations adopted in 2011 by the supervisor (KNF) to regulate consumer credit (in particular limits on the DTI ratio) were strongly criticized by the Union of Polish Banks on the grounds that they would lead to the development of consumer credit by non-bank financial companies.

2 – Attempts by political authorities to influence the macroprudential mandate in order to promote objectives other than financial stability alone

In some countries, the government may seek to assign objectives other than financial stability alone to the macroprudential mandate. In India, the body responsible for the macroprudential mandate, the Financial Stability and Development Council, has objectives that include financial stability, financial sector development, and financial inclusion. In the United Kingdom, the macroprudential body, the Financial Policy Committee (FPC), has financial stability as its primary objective and, subject to achieving this objective, supporting the government’s economic policy. Although the FPC is dominated by the Bank of England, there were several attempts by the British government in 2013 to increase its influence over its decisions [4].

The composition of the entity in charge of the macroprudential mandate, or where no such entity exists, the distribution of macroprudential responsibilities among public authorities, also provides insight into the political economy of PMPs, as their governance partly determines the government’s power of influence. The desire of finance ministries to exert influence often becomes apparent when the macroprudential governance structure is chosen. In our sample, the finance ministry plays a leading role within the macroprudential entity in a large number of cases: South Korea, Colombia, Hong Kong, Turkey, India, and Canada. However, the role of the finance ministry is not the only criterion. It is important to distinguish between the situations in these countries, as political pressure on the exercise of the macroprudential mandate to promote objectives other than financial stability may be strong in some countries (South Korea, Hong Kong) and virtually non-existent in others. Furthermore, when the central bank is the leader in macroprudential matters (as is the case in our sample in New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and Sweden), there is a risk of conflict of interest between its objectives as a monetary authority and as a macroprudential regulator. In this case, it is possible that the inflation objective will take precedence over the financial stability objective.

3 – Provisions promoting public acceptance of macroprudential policies

Certain provisions help to limit public opposition to MPPs, in particular the targeting of assets to which MPPs apply. In Korea, MPPs affecting the real estate sector have, from the outset (2002), targeted areas of high speculation rather than the entire territory. The application of the measures also depends on the borrower’s personal and financial situation, which allows certain categories of the population to be exempted. This is also the case in Hong Kong, where limits on LTV ratios can target specific assets (properties above a certain value and/or not intended as a primary residence). These adjustments largely defuse public opposition to MPPs.

Additional measures can also be put in place to limit the impact of PMPs on households. Mechanisms are available to limit the restrictive effects of PMPs for certain solvent households. Limits on LTV ratios are a crude instrument that excludes ex-ante first-time buyers who do not have a substantial financial contribution. To remedy this problem, Hong Kong introduced a public guarantee mechanism in 1999, the Mortgage Insurance Program, via the Hong Kong Mortgage Corporation (HKMC) [5]. In Singapore, macroprudential measures aimed at limiting real estate speculation are accompanied by provisions promoting home ownership for low-income Singaporeans [6].

Conclusion

These reflections on macroprudential measures allow us to formulate a few recommendations to improve their acceptability and effectiveness:

– The proliferation of tools is one of the main complaints made by banks about macroprudential policy. Public authorities must therefore strive to ensure the clarity of MPPs by avoiding overlapping tools and recalibrating them too frequently and arbitrarily.

– To be well accepted by banks, MPPs must apply to the widest possible range of lending activities, both banking and non-banking.

– Targeting assets to which LTV limits apply helps to limit public opposition (real estate in speculative areas, properties above a certain value, second homes).

– Mechanisms that facilitate access to home ownership for first-time buyers or less affluent households can promote public acceptance of macroprudential measures.

Notes:

[1] Brazil, Canada, Colombia, South Korea, Finland, Hong Kong, Hungary, India, Norway, New Zealand, Poland, United Kingdom, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland, and Turkey.

[2] The loan-to-value ratio indicates the proportion of an asset, generally real estate, that is financed by borrowing.

[3] The debt-to-income ratio indicates the proportion of an individual’s monthly income allocated to loan repayments.

[4] In April 2013, the Chancellor of the Exchequer sent a letter to the FPC asking it to give particular consideration to the impact of its decisions on the country’s economic recovery (Osborne, 2013). In this letter, the government indicated that, in the short term, it may be desirable for the FPC to prioritize the objective of supporting the government’s economic policy over that of financial stability (or at least to place these two objectives on an equal footing). Certain appointments to the FPC may also suggest the government’s desire to exert greater influence over the body’s decisions (notably the appointment of Clara Furse). The British banking sector’s share of national wealth and London’s role as an international financial center could explain why the government is seeking to limit macroprudential constraints, even beyond a desire not to restrict credit to the economy.

[5] This guarantee covers the portion of bank credit exceeding the 70% LTV cap, allowing banks to lend up to 90% of the value of the property. Similar programs also exist in the United States, Canada, Korea, and Malaysia.

[6] However, MPCs that promote growth and credit development will not automatically enjoy public support. In Korea, the recent shift in MPCs towards supporting growth, through greater tolerance for household debt (relaxation of limits on LTV and DTI ratios and creation of a household debt restructuring fund, the » People’s Happiness Fund « ) has been strongly criticized because, according to some observers, it creates a risk of moral hazard (Financial Times, 2013).

References:

– Bénassy-Quéré, A., B. Coeuré, P. Jacquet, and J. Pisani-Ferry (2012), Politique Economique, De Boeck,3rd edition.

– Financial Times (2013), “South Korea launches household debt plan,” in Financial Times, March 29, 2013.

– International Monetary Fund (2012), “The Interaction of Monetary and Macroprudential Policies – Background Paper,” International Monetary Fund, December.

– International Monetary Fund (2013a), “The Interaction of Monetary and Macroprudential Policies,” International Monetary Fund Board Paper, January.

– International Monetary Fund (2013b), “Key Aspects of Macroprudential Policy,” International Monetary Fund, July.

– Osborne, G. (2013), “Remit and Recommendations for the Financial Policy Committee”, letter dated April 30, 2013 from the Chancellor of the Exchequer to Mervyn King, Governor of the BoE, April.