Summary:

– Germany’s declining and aging population is its main challenge for the coming years.

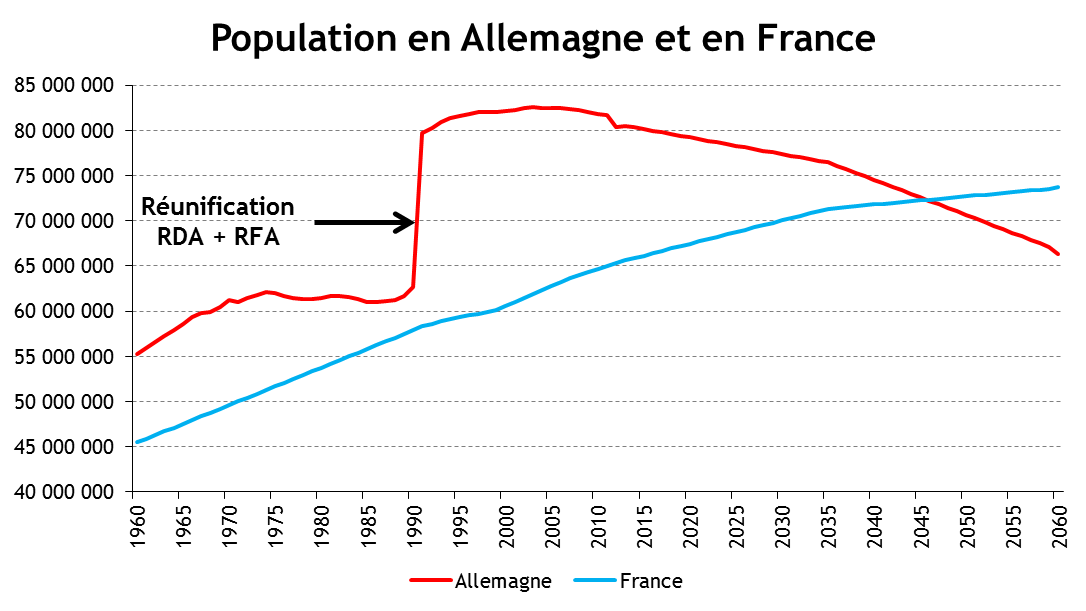

– By 2045, France’s population could exceed that of Germany.

– To counteract its population decline, Germany has taken measures to increase its birth rate, but these do not seem to be sufficient to counter this phenomenon.

– Immigration and the economic situation in southern European countries may present an opportunity in this regard.

Germany has undeniable economic strengths: low unemployment, record foreign trade surpluses, and healthy public finances. However, the longer-term outlook is less positive, particularly due to its declining and aging population. Immigration (from southern Europe) seems to offer at least a partial short-term solution to this structural problem.

Demographic trends in Germany

The demographic trajectories of Germany and France are divergent. Indeed, the two countries are in radically different situations. Germany has a population of around 15 million more than France (80.5 million versus 65.5 million, respectively). However, while France has been able to maintain a satisfactory fertility rate, which is almost sufficient to guarantee long-term population stability, Germany’s declining birth rate will lead to a rapid and significant decline in population and a much more pronounced aging of the population than in France. As a result, projections indicate that by 2045, France is expected to have a larger population than Germany. By 2060, Germany is expected to lose almost 15 million inhabitants and have a population of 66 million, compared with nearly 74 million in France, which will have gained 9 million during the same period. As a result, in 2060, the proportion of people aged 65 and over will reach almost one-third of the population in Germany, compared with 27% in France.

The divergent trajectories between these two countries are essentially the product of history. In Germany, the most numerous generations are those born between the 1930s and 1945 (the Nazi period, which saw a strong incentive to have children). The second wave of births occurred in the mid-1960s with the children of the generations born during this period. Conversely, in France, the generations of the 1930s are small. After the Second World War, while Germany experienced a baby crash, France entered a period of baby boom. The birth rate then gradually declined from the crisis of the 1970s onwards.

Demographic challenge for Germany

Germany’s demographic situation is very poor. The rapid aging of its population is directly linked to its low birth rate. With 670,000 births per year and 870,000 deaths, the country has a birth deficit of 200,000 inhabitants per year. As a result, Germany is one of the top three countries in the world with the smallest proportion of young people: only 13% of the population is under 15 and only 22% is under 25. With 18 births per 1,000 inhabitants, Germany has a very low fertility rate of 1.36 children per woman on average, whereas a rate of 2.1 is required to maintain the population at its current level.

The consequences for Germany will be significant. Beyond issues relating to the labor market (difficulty in increasing the employment rate), productive capacity (difficulties in increasing innovation and productivity), and debt sustainability (lower with a smaller population), the main problem concerns the burden of public pension expenditure, which will automatically increase. In this respect, despite the retirement age already having been raised to 67, this threshold is already insufficient. Future German employees will not have the means to meet the needs of their retired elders. As a result, Germans’ retirement seems increasingly dependent on their accumulated wealth. This is one of the reasons (along with the trauma of hyperinflation between the two world wars) why Germans do not want too high inflation in Europe, as this would erode the value of their assets (J.M. Keynes’ « euthanasia of the rentier »).

Aware of this challenge, Germany is developing policies to address it. The country has increased its support measures to catch up on its demographic deficit and halt its decline. In addition toElterngeld, which is a year of parental leave paid for by the state, the two main and most recent measures are a guaranteed place in a nursery or with a nanny for children over one year old (compared to over three years old previously), and a bonus of between €100 and €150 for families who decide to look after their children themselves. While the first measure is widely accepted (despite likely practical problems ahead in a country known for its lack of infrastructure in this area), the second is a subject of debate within German society. It should also be noted that there are plans to reduce the weekly working hours of women with dependent children.

The « solution » for unemployed people from southern Europe

Germany is rather inclined to help young people from southern Europe. The proportion of this population group that is unemployed has skyrocketed (+50% in five years) with the crisis in these countries (Spain, Greece, Italy, Portugal). With more than 50% of under-25s unemployed, Greece and Spain have the worst results in this area, while youth unemployment in Germany is only 8% (for comparison, in France the youth unemployment rate is around 25%). As such, Germany has proven to be a solution to unemployment for many foreigners. In fact, Germany is the country that saw the most foreign arrivals in 2012, absorbing one million migrants, which is a record since 1995/1996. Between 2011 and 2012, the number of Greeks settling in Germany jumped by 75%, as did the number of Portuguese and Spanish (+50%) and Italians (+35%). In total, more than 130,000 Southern Europeans moved to Germany in 2012, and probably at least as many in 2013.

Declining demographics and the need to find labor for industry are behind this influx of foreign populations. Most of the population influx is highly educated, as unemployment among university graduates is 20% in Greece and 17% in Spain, compared to only 2.5% in Germany. Some countries are beginning to worry because this implies, on the one hand, a brain drain that is necessary for the « reconstruction » of southern countries and, on the other hand, a financial loss in terms of training that does not benefit the countries of origin. Ultimately, the overall risk of this policy is that it will widen the gap between Northern Europe (productive and skilled) and Southern Europe (which faces a number of structural economic problems), as well as jeopardizing the future growth of Southern European countries, especially if these populations remain in Germany. At the same time, the overall advantage is linked to the rebalancing of productivity levels and the reduction in the cost of unemployment for Southern European countries, with populations moving from unemployed status in their own countries to employed status in Germany.