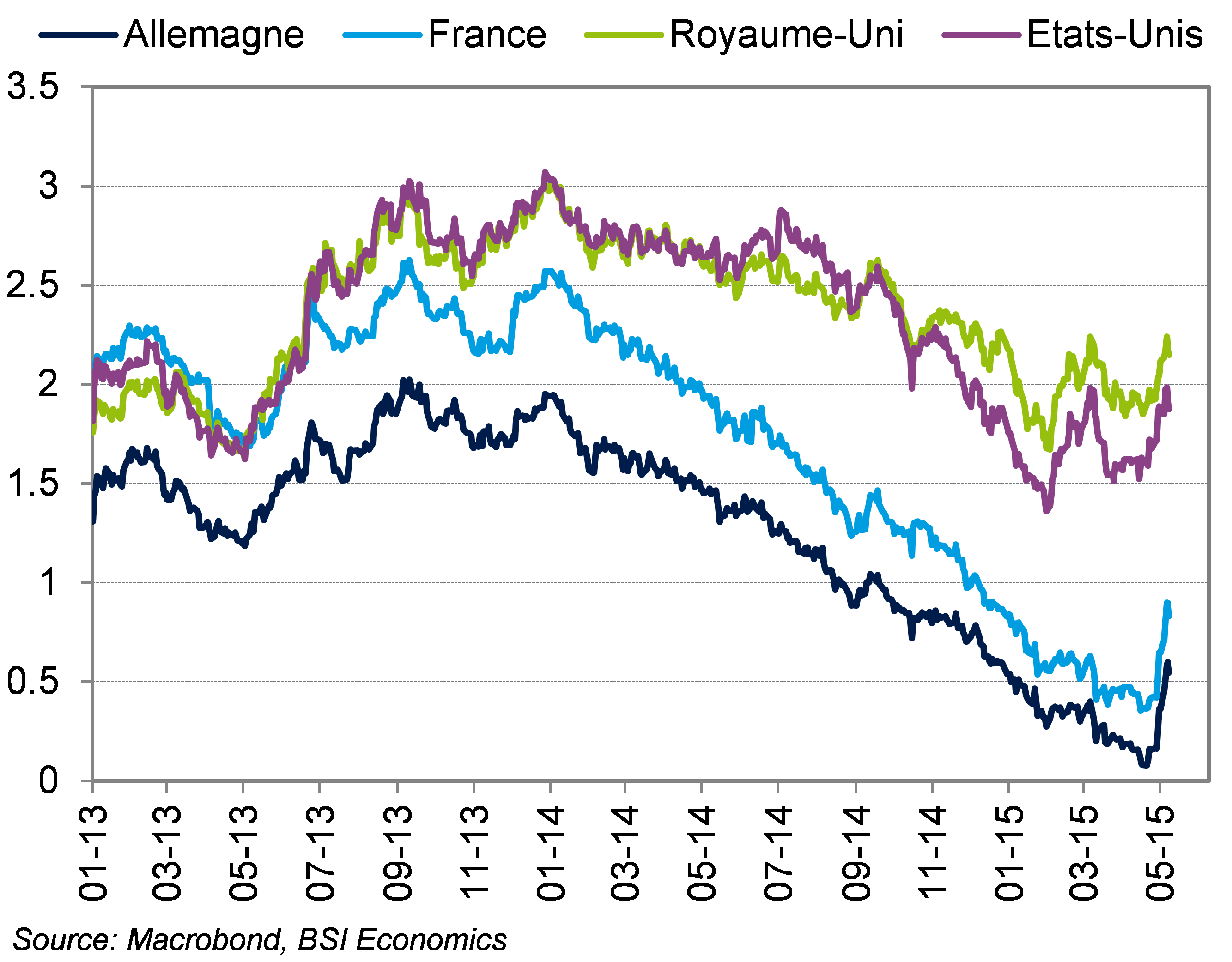

News: German bond yields rose very quickly. In less than a month, the Bund climbed more than 50 basis points to return to around 0.62% (figure as of May 8, 2015), after coming dangerously close to negative territory. Here we look at the possible causes of this meteoric rise in the Bund.

The very rapid and sharp rise in long-term German rates has already been widely discussed. We offer a simple interpretation of this sell-off ( rapid sale of financial securities; the increase in supply leading to a fall in the value of the security and therefore, in this case, to a rise in interest rates) on the Bund and review the factors that may explain it, some of which are global and others more local.

Interest rates on 10-year sovereign bonds (in %)

Oil prices play an important role

Although we are talking here about the rise in German bond yields, some other developed countries have also seen their long-term rates rise, albeit to a lesser extent, over the same period (United States, United Kingdom, other eurozone countries, etc.). This is therefore a global factor that should be highlighted, and we see it as the effect of rising oil prices. Since mid-March, the price of oil (Brent) has climbed by more than 20%, and this surge has been accompanied by higher inflation expectations in most developed countries. Nominal bond yields had not followed this rise in break-even inflation rates (the 5-year forward 5-year inflation swap, which is one of the main measures of inflation expectations monitored by the ECB, rose from 1.5% in mid-January to 1.8% in early May), and we can therefore see this as a catch-up phenomenon.

The ECB’s QE weighs on bond yields in member countries

At the eurozone level, the ECB’s QE is undeniably weighing on bond yields in member countries. Another explanation for this sharp rise in the Bund can be found in the Public Sector Purchase Program (PSPP) launched by the ECB last March. In April, the Eurosystem purchased bonds with shorter maturities than in March, putting the Bund under further pressure and preventing it from benefiting from strong demand from the Eurosystem. As a result, 10-year German sovereign bonds had to be purchased by investors other than the ECB, and the risk premium on these bonds increased (interest rates rose).

Profit-taking is widespread

Finally, a more local factor may also explain why the Bund rose much more than the 10-year OAT (French Treasury bonds), for example. After more than five quarters of almost continuous declines in German bond yields, it is logical to see profit-taking (when the price of a financial asset rises, it is legitimate to sell part of these assets and thus convert potential capital gains into actual capital gains). Profit-taking is also visible across most asset classes (equities, bonds, commodities, and even certain exchange rates). Given that long-term German rates were dangerously close to negative territory, it was logical that the sell-off would be more pronounced for German bonds than for those of other developed countries.

The evolution of German bond yields would therefore remain dependent on several factors: fluctuations in oil prices, a potential revaluation of the dollar, and the ECB’s QE program, which has only just begun. Of the €1.1 trillion promised by Mario Draghi, only €118 billion has been injected, and there are still around €200 billion of German sovereign bonds to be purchased under the PSPP. As a result, the ECB’s QE program, given its size, should continue to exert downward pressure on bond yields in the eurozone and therefore on the Bund.