Summary:

– The structural crisis that Finland has been facing since the mid-2000s has been exacerbated by the collapse of international trade in 2009 and the sluggish growth of its trading partners since then.

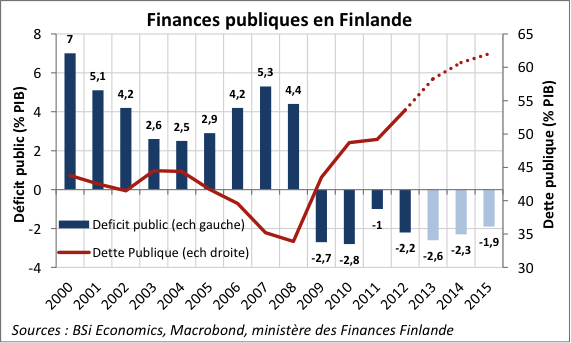

– The deterioration in public finances that began in 2009 is set to continue, with the government even planning to exceed the Maastricht limits, with public debt expected to reach 60.7% in 2014.

– In fact, in order to stimulate growth potential and restore the sustainability of public debt in the long term, the government and social partners have agreed on a set of policy choices.

– Finland remains, however, the last country in the eurozone (excluding Luxembourg) to enjoy a AAA rating with a stable outlook from all three rating agencies.

For the second consecutive year, the Finnish economy will see negative growth. After a 0.8% decline in GDP in 2012, the recession is continuing in 2013, with the government now forecasting growth of -0.5%. Since 2005, Finland has faced a mounting series of structural and cyclical challenges, with the country grappling not only with a crisis in its main economic sectors, namely information and communication technologies (ICT) and wood and paper, but also with a decline in international demand, which has severely constrained the country’s export potential. In order to respond to these various challenges, a genuine « consensus » has emerged within the country: the coalition government (no less than six parties in power) has voted through a sweeping reform plan and union representatives have agreed to very low wage increases. These measures are intended, on the one hand, to improve Finland’s international competitiveness and, on the other, to restore the sustainability of the country’s debt, which is set to exceed the Maastricht criteria for the first time (60.7% of GDP in 2014).

The slowdown in the Finnish economy is due to structural changes in its economy, against a backdrop of slowing growth among its trading partners.

Since 2005, the Finnish economy has undergone structural changes in both the ICT and wood and paper sectors. While these two sectors accounted for 5.5% and 7% of GDP respectively in the early 2000s, their share has steadily declined, reaching 1.5% and 4.5% in 2012. The decline in structural demand for paper, particularly in a media environment where information is increasingly being digitized, has significantly eroded the paper industry’s business. Similarly, Nokia’s poor commercial performance over the last six years, with the group failing to establish itself in the smartphone market, has significantly deteriorated the group’s financial profitability, forcing it to implement extensive restructuring plans, particularly in Finland. This is all the more significant given that these sectors accounted for a very large share of the country’s goods exports. The relocation of production (Nokia closed its last phone production plant in Finland in the summer of 2012) and the decline in Nokia’s sales largely explain Finland’s poor export performance since 2008. In 2007, Finnish mobile phone exports were worth €6.9 billion (31 million units sold), accounting for around one-tenth of Finland’s total exports, whereas in 2012, they amounted to €0.9 billion (4 million units), or only 1.7% of the country’s total exports.

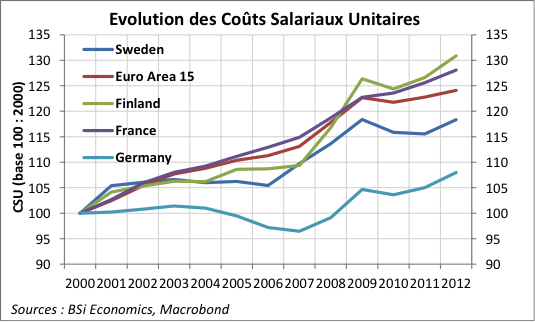

Furthermore, the country’s poor export performance can be explained as much, if not more, by a loss of price competitiveness of Finnish products as by the fall in international demand in a context of global slowdown. Indeed, Finland’s unit labor costs, which relate productivity to hourly costs, have risen steadily in recent years and have increased by more than 30% since 2000, a much faster rate than its main competitors, Sweden and Germany. This effect was amplified in 2010 by the generous wage agreement negotiated by the social partners, which had a significant impact on labor costs in Finland at a time when global demand for Finnish goods was falling. The structure of exports shows a high degree of cyclicality in products. The predominance of capital goods (28% of exports in 2012) and intermediate goods (50%, including products from the wood and paper industry and the metallurgical industry) is constraining the country’s exports, against a backdrop of falling private investment in Europe. Furthermore, there is a strong bias towards exports to the EU, which accounts for 55% of exports, with Finland being relatively closed to the BRICS countries, except for Russia, which accounts for 10% of its exports. All these factors have deteriorated Finland’s current account balance, which in 2011 became negative for the first time since 1993 (when the country suffered from the collapse of its foreign trade in the wake of the fall of the USSR).

Pressures on the sustainability of public finances emerged in the wake of this crisis, which was both structural and cyclical.

Although the crisis in Finland began well before 2009, following the collapse of its main growth drivers, it was the massive decline in international trade that weighed heavily on the growth of the Finnish economy, which remains a small, open country dependent on world trade. The sharp recession of 2009, at -8.5%, which coincided with a 21% collapse in the volume of its exports, led to a drastic decline in budget revenues and a combined increase in public spending, linked to automatic stabilizers, thus weighing heavily on public finances. In fact, since 2009, successive Finnish governments have only presented deficit budgets, albeit below the Maastricht threshold.

However, a closer look at the public finance statistics raises the question of how the debt trajectory can be so explosive, having grown by 25.7 points between 2008 and 2014, while the deficit remains below 3%. In fact, while the deficit appears « virtuous » (-2.2% of GDP in 2012 and -2.6% in 2013), it is actually the traditional surplus of pension funds, at 2.5% of GDP in 2012, that has made it possible to keep the Maastricht deficit under control. Private pension funds manage the social security contributions of employees and employers, which, from an accounting point of view, allows the state to include the funds’ surpluses in the calculation of the public deficit (since the assets managed by pension funds come from compulsory levies). However, these funds do not finance Finland’s public debt, which accounts for barely 2% of their total assets. It is therefore the combined deficits of the central government and municipalities that have contributed to the sharp rise in public debt over the last two years, since, cumulatively, these amounted to 4.9% in 2012, 4.7% in 2013, and 4.4% in 2014 (forecast).

These multiple slippages in public finances have led to a rising trajectory of public debt, which for the first time since the creation of the eurozone is expected to exceed the 60% of GDP threshold, reaching 60.7% in 2014 and finally 62% in 2015. Nevertheless, the public authorities seem to have become aware of the challenge of ensuring the sustainability of public finances in the context of an aging population. The dependency ratio (population aged 15-60 / population aged 60 and over) is expected to increase by nearly 20 points between 2008 and 2030, from 25% in 2008 to 44% in 2030, the sharpest increase in Europe. This demographic trend will, on the one hand, reduce the pension fund surplus in the long term (through a decline in social security contributions linked to the decline in the working population and an increase in pension benefits) and, on the other hand, increase public spending.

Will the reform program announced by the government be enough to stimulate Finland’s growth potential and restore long-term debt sustainability?

Faced with a growth deficit and tensions related to the long-term sustainability of public finances, Finland’s coalition government has announced structural reforms to be implemented by 2017. The Ministry of Finance estimates Finland’s sustainability gap (which measures the fiscal efforts needed to ensure the stability of public debt) at €9 billion, or 4.7% of GDP. These announcements focus on rebalancing local public finances (€2 billion budget cut), improving the efficiency of public services (merging social and health services and opening them up to competition), extending working careers by two years (delaying retirement by 1.5 years and bringing forward the start of working life by 0.5 years), reducing structural unemployment (shortening the duration of unemployment benefits and promoting part-time work), and finally stimulating the economy’s production potential (wage moderation, combating structural rigidities in the economy).

In addition, in order to restore corporate margins and attract foreign direct investment (FDI) to the country, the government has decided to cut corporate tax by 4.5 points, from 24.5% to 20%. This reduction follows on from the one already initiated in 2012, when corporate tax was cut by 1.5 points. Through this supply-side policy, the government is seeking to stimulate investment and job creation after several quarters of sharp decline in investment and a slight rise in the unemployment rate, which is now close to 8%. Faced with uncertainties surrounding the economic recovery among Finland’s main trading partners, the country’s businesses have remained cautious, resulting in a sharp drop in private investment.

In addition, the social partners have agreed on a very slight increase in wages. This is a comprehensive agreement that will apply to all sectors in the country for the period 2014-2016. This moderate wage agreement should enable Finland to overcome its growth deficit by focusing on the rebound in exports. However, while the combined effect of a reduction in corporate income tax and wage moderation will restore corporate margins and stimulate investment, the other component of domestic demand, namely consumption, is likely to remain sluggish in the short and medium term. Indeed, this contraction in purchasing power, albeit in a low-inflation environment (price index at 1.6% and 2.1% for 2013 and 2014), is likely to constrain household consumption. Finland is therefore deliberately playing the foreign trade card in order to revive its growth.

What about Finland’s AAA rating and the status of its debt as a safe asset?

To date, only Standard & Poor’s has commented on the economic situation and public finances in Finland, confirming the country’s rating and outlook, namely AAA with a stable outlook. For the agency, the low level of public debt reflects the sound management of public finances in the country, which, given the prosperity of Finns (one of the highest GDP per capita in the eurozone, at $35,800 in purchasing power parity), is a positive and necessary signal for the rating, as is the quality of its institutions. However, S&P highlights the risks associated with the aging population, both in terms of public spending (pensions and healthcare and dependency costs) and potential economic growth (a combined decline in productivity and the working population). These factors could lead S&P to downgrade the country’s rating if the structural reforms undertaken do not result in significant gains in terms of budgetary savings and stimulation of growth potential. As a reminder, Finland is the last country (along with Luxembourg) to be rated AAA, with a stable outlook, by the agencies.

Against a backdrop of slowing demand among its trading partners, Finland is therefore facing multiple structural challenges, requiring a concrete and far-reaching action plan. In fact, all stakeholders are facing this crisis in the same way that they had to make many sacrifices to emerge from the crisis of the early 1990s. Finland is a « country of consensus, » as evidenced not only by the current government coalition but also by the ability of social partners to reach agreement within companies. With no direct equivalent in the French lexicon, the Finnish concept of « Sisu, » or perseverance/tenacity/courage, is one of the strengths of the Finnish people in overcoming economic difficulties that should not be overlooked.