Summary:

– The sluggish economic climate in the eurozone is affecting the attractiveness of its member countries in the eyes of foreign investors.

– Despite this, each of the eurozone countries has many assets that can attract foreign direct investment, which comes mainly from their monetary partners.

– Overcoming the lack of confidence and cohesion in European economic integration, which is also evident in the capital markets, is therefore key to their recovery.

– The economic benefits of well-directed investment flows are high and should make them a central element of public policy.

1 – What is direct investment?

A direct investment is a movement of capital from one economy to another with the aim of creating a business or acquiring at least 10% of the share capital of an existing business in order to exert influence or carry out a sustainable activity.

There are two types of direct investment flows:

– Investments in the domestic economy by non-residents (inward FDI)

– Direct investment abroad by residents (outward FDI)

The balance of these two flows results in a balance that is found in the financial section of the balance of payments. The abbreviation FDI is commonly used to refer to both foreign direct investment and foreign direct investment.

There are several reasons to take an interest in FDI. First, to gauge a country’s attractiveness in the eyes of the rest of the world. Depending on the sectors invested in, the quality of infrastructure, the skills and cost of labor, and the tax burden are highlighted as decision-making criteria by investors in their international arbitrage. Furthermore, FDI flows reflect investor confidence in a region’s economic potential. In the eurozone, we can go further and say that the importance of flows between countries in the monetary union is one of the barometers of the zone’s economic integration. Thanks to the creation of the euro, these flows have been facilitated and are an important element of economic convergence, skills transfer, and therefore growth.

Net FDI inflows

The balance we have just defined is actually the result of four types of flows. Investments in the national economy by non-residents give rise to a positive capital flow in the balance of payments. If this capital is withdrawn, the flow is negative. The difference between these two flows, positive (credit) and negative (debit), corresponds to net FDI inflows. Thus, if the latter are zero (or even negative) over a period, this does not mean that no investments were made, but that the volume of divestments equaled (or even exceeded) them. Similarly, investment flows abroad by residents result in a negative capital flow for the national economy. If this capital is repatriated, the flow then becomes positive.

Let’s take an example in France. By purchasing 70% of the Paris Saint Germain football club in 2011 and then the remaining 30% in 2012, the Qatari investment fund QIA created a positive capital flow for France over the last two years. If it were to sell its shares in a few years’ time, this would represent a negative capital flow, which would have the same impact on France’s FDI balance as French investment flows into foreign economies. Similarly, if a French group divests from a foreign economy, this corresponds to a positive capital flow for France, and has the same impact on the FDI balance as QIA’s acquisition of a stake in PSG, even though the implications are not at all the same.

2 – Who are the foreign investors in the eurozone countries?

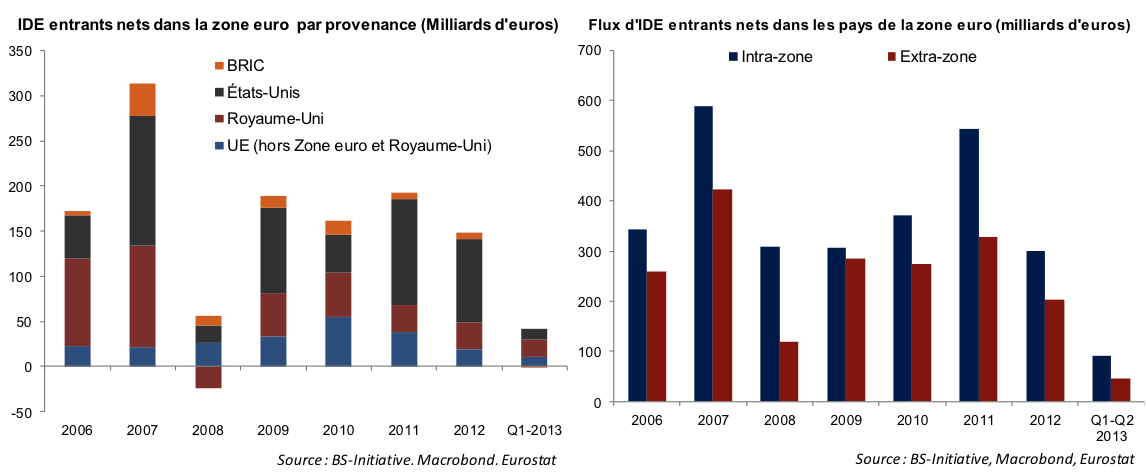

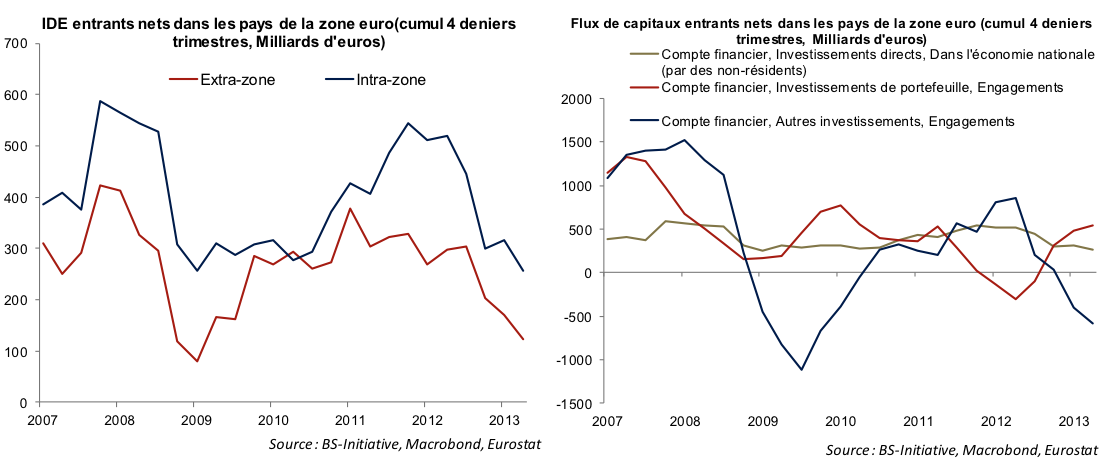

After reaching a record high in 2007, net FDI inflows into eurozone countries (both intra-zone and extra-zone) have never returned to their pre-crisis levels. The financial crisis of 2008 and the sovereign debt crisis in the eurozone from 2010 onwards halted the growing momentum of FDI inflows, particularly from investors outside the zone (see chart).

The United States and the United Kingdom are major contributors, as are several European countries (Switzerland, Norway, Finland, and Denmark). However, net FDI inflows into eurozone countries come mainly from their monetary partners. The BRIC countries, particularly China, whose trade surpluses give it significant investment potential, remain relatively modest contributors. The difference in production costs between advanced and emerging economies is currently leading them to limit their investments to the establishment of distribution structures and regional management.

3 – Which sectors and countries receive FDI in the eurozone?

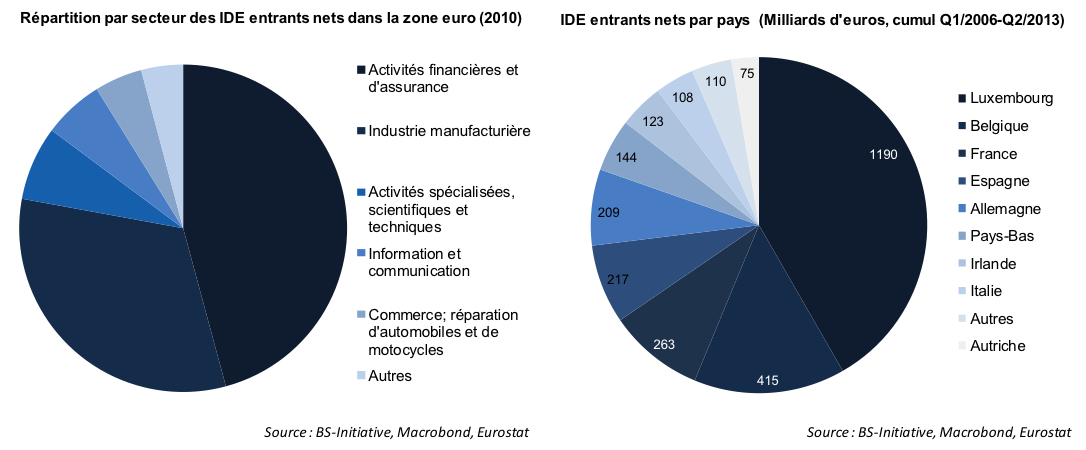

Given the importance of intra-zone flows (which account for around 60% of total FDI inflows) and the economic heterogeneity of the EMU, a country-by-country analysis is important to understand the main characteristics of FDI flows in the euro area. European countries remain attractive. Depending on the country, each with its own specific characteristics and strengths, the quality of infrastructure (France, Belgium), taxation (Ireland), quality (Germany), or the relatively low cost of labor (Spain) are attractive assets for investors. Thus, in the 2013 ranking by A.T. Kearney on foreign direct investment prospects (Foreign Direct Investment Confidence Index), six European countries are in the top 20, including three eurozone countries (Germany7th, France12th, Spain16th).

Which eurozone countries are most popular with international investors? In terms of cumulative net FDI inflows since 2006, the largest recipient among the eurozone countries is… Luxembourg. However, this finding must be put into perspective. Most of the FDI it receives (and issues) corresponds to capital flows that pass through the country and cover group financing and asset holding operations via Special Purpose Entities (SPEs). Belgium ranks second, with its location at the heart of Europe, high-quality infrastructure, and skilled workforce making it a major recipient of FDI in the specialized, scientific, technical, and real estate sectors (two-thirds of FDI received) and financial intermediation (one-quarter of FDI received). In third place is France, whose attractive tax regime for research and development attracts investment mainly in high-tech activities (particularly in the development of aeronautical, rail, and air equipment). Spain (industry and energy) ranks fourth in this classification, Germany (business services and manufacturing) fifth, and the Netherlands (financial activities in particular, energy, and industry) sixth. Italy ranks low (8th) and, despite the size of its economy, trails behind Ireland (7th).

4 – The economic benefits of FDI

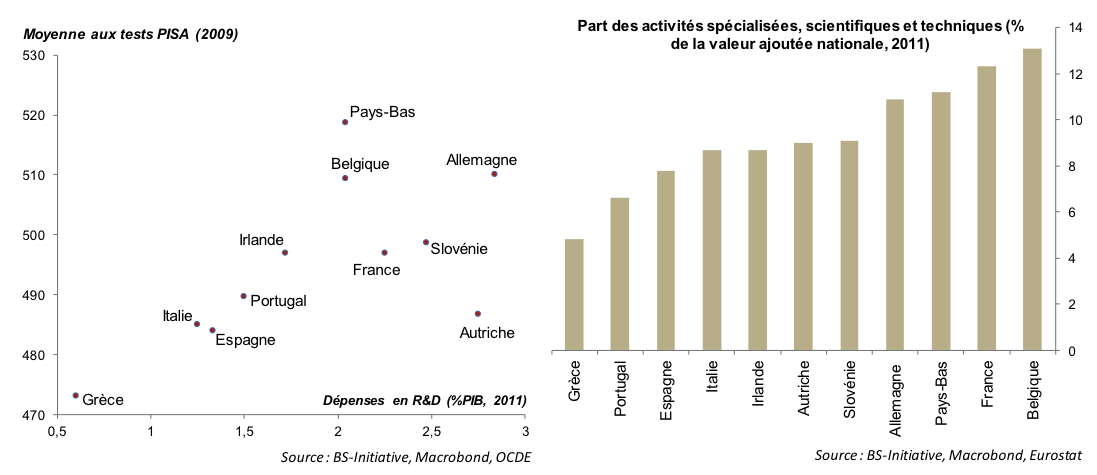

Inward FDI flows are important for economic development because they involve the transfer of skills and technology to the recipient country, and therefore have an impact in terms of growth (and job creation) that can be significant depending on the sectors concerned. In order to attract direct investment in high value-added sectors and reap the full benefits, the recipient country must have the necessary infrastructure and skilled labor. Spending on R&D and education is essential in this regard in order to create attractive investment conditions so that technology-intensive projects can be undertaken and create synergy between domestic know-how and foreign financing and skills transfers.

Among the main recipients of FDI in the euro area, those that have implemented R&D spending policies and whose populations are well educated enjoy a significant share of specialized, scientific, and technical activities. Similarly, these countries are the best placed in terms of net FDI inflows in this sector; Germany, France, Belgium, Austria, and the Netherlands have investment positions that reflect the largest net capital inflows.

Conversely, countries with lower production costs (wages, taxation, etc.) attract investments with lower technological density but serve, for example, as a point of entry into the European market, which remains attractive due to its size (the European Union remains the world’s leading economic power in terms of GDP). Wage adjustments in Spain have enabled it to restore its competitiveness and return to a positive trade balance (also due to compressed domestic demand and a fall in imports). The continuation of its reindustrialization through domestic and foreign investment, made more attractive by falling labor costs, could perpetuate this trend.

5 – Towards a rebound in FDI in the eurozone?

As we have seen above, net FDI inflows are a balance and may be negatively affected by investors’ de-exposure. However, direct investment positions remain more stable than other portfolio investment positions and other investments. Even though some countries (notably Belgium, Ireland, and Luxembourg) have periodically experienced sharp withdrawals of capital in the form of FDI (which varies depending on the sectors invested in), FDI is logically the least volatile and least reactive part of the financial account of the balance of payments.

Across the eurozone as a whole, net capital inflows from portfolio investments (shares, bonds, etc.) reached a negative low in mid-2012. This corresponds to a reduction in foreign investors’ exposure to portfolio investments. The trend appears to be reversing. However, the other investments account (interbank loans, trade credits) shows that domestic declines are still ongoing, although 2013 could mark a turning point in this trend after an alarming final quarter in 2012.

The disastrous second quarter of 2013 in terms of net FDI inflows into eurozone countries (a record €3 billion) confirms the idea that they are reacting with a delay compared to other components of the financial account of the balance of payments. Over the same period, the level of flows from countries outside the eurozone reached its lowest level since mid-2008 (+€14 billion). 2013 will therefore not be the year of recovery for foreign direct investment in the eurozone. However, the trajectory of other types of investment, particularly portfolio investment, gives hope for the beginning of a turnaround that could materialize in 2014.

Conclusion

After several years of sustained growth, net FDI inflows into eurozone countries have been chaotic since the onset of the financial crisis in 2008, followed by the sovereign debt crisis. The poor figures for the first half of 2013 illustrate investors’ caution. The continued return of confidence seen in the capital markets and the strengthening of the prospects for a short-term recovery in the eurozone, as well as the implementation of national public policies that are attractive to investors in the medium term, will determine the return of direct investment.