Summary:

– Life insurance is one of the preferred investments of French households, and its secure compartment, the euro fund, continues to record significant inflows (€22.4 billion in average annual net inflows since 2009).

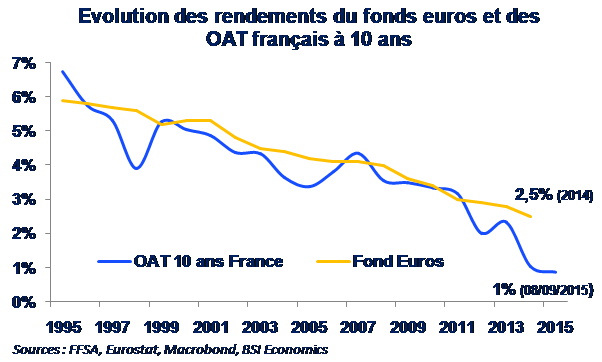

– Although returns on euro fund contracts have been falling for 20 years (-4.4 percentage points), they remain high given the low level of French sovereign bond yields. This situation could weigh on the solvency of life insurers if low interest rates persist.

– The current situation is reminiscent of that in Japan in the late 1990s, when several life insurers went bankrupt, forced by a prolonged period of low interest rates.

– In Europe, and particularly in France, life insurers are not in such a bad position compared to their European neighbors. However, changes must be made quickly, particularly in terms of their remuneration strategy and choice of financial assets, so as not to significantly threaten the stability of the European financial system.

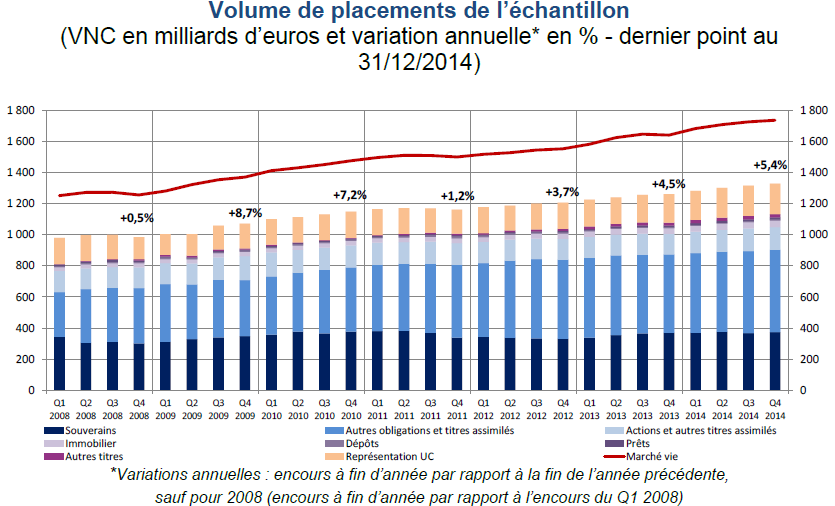

Life insurance is one of the preferred investments of French households, with outstanding amounts reaching €1,572.1 billion (73% of GDP) in July 2015 according to the French Federation of Insurance Companies, far ahead of the Livret A savings account, which does not exceed €260 billion. Life insurance continues to attract savings in 2015, with net inflows exceeding €15.7 billion between January and May 2015. The popularity of life insurance can be explained in particular by the risk/return ratio offered by euro funds, a secure life insurance compartment that accounts for nearly 80% of total life insurance assets.

However, in a low interest rate environment, the growing gap between the returns on euro fund contracts and the yield on French sovereign bonds (the main investment in euro funds) could pose a risk to life insurers’ margins. If this situation were to continue, it would be a source of significant concern for the stability of the life insurance sector.

1 – The incompatibility between low interest rates and high returns on euro funds

1.1 – High guaranteed minimum rates

Although there are several types of life insurance (see appendix at the end of the article), euro funds, due to their characteristics[1]and its weight in the total amount of life insurance in France[2], are the ones that attract the most attention.

With euro funds, the various life insurance distributors are required to offer their customers a minimum return (as a percentage of the yield) each year, so that savers who have taken out a policy are assured of a guaranteed minimum annual rate on their savings. According to the EIOPA (European Insurance and Occupational Pension Authority), out of a sample of 64 companies offering life insurance in the European Union, this guaranteed rate is around 3% for the majority of them, which is extremely high… especially in the current low interest rate environment!

1.2 – A widening gap

In 2014, 65% of sovereign bond investments in the European Union by life insurance companies were in French sovereign bonds, representing 20% of total bond investments in life insurance (more than €314 billion). The return on euro funds follows the variation in sovereign bond rates.

For nearly 20 years, the return on euro funds in France has followed the downward trend in French bond yields. Year after year, the return on euro funds has declined, much to the chagrin of French savers who have invested their savings in this vehicle, even though very low inflation in recent years has « preserved » the real return. Despite an average return on euro fund contracts of 2.5% in 2014 (compared to 5.3% in 2000), this seems too high. Indeed, the gap between the return on 10-year French government bonds and that of euro funds is widening (see chart below).

In this context, the Banque de France and the Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution (ACPR), whose role is to supervise banks and insurers, have been calling for life insurance distributors to lower the return on euro funds for a year now, so that it is more closely linked to changes in sovereign bond yields.[3]. In a May 2015 note, the International Monetary Fund (IMF)[4]also expressed concern about the vulnerability of life insurers in Europe to a Japanese-style scenario.

2 – Insurers’ solvency risk, the risk of a Japanese scenario

In the late 1990s in Japan, these same conditions led to the bankruptcy of eight major life insurers. Three categories of risk can be identified in order to understand the types of scenarios that the life insurance sector in Europe could face. These risks are interdependent and, if they were to occur simultaneously, which would be the worst-case scenario, a Japanese-style scenario could unfold.

2.1 – Risk of imbalance in insurers’ balance sheet durations

A persistent gap between life insurance contract returns, low key interest rates, and low bond yields could prove destabilizing for life insurers.

The liabilities side of life insurers’balance sheets includes guarantees contained in old life insurance contracts, which, as we have already seen, are quite high. In addition, as life insurance is a long-term investment, insurers invest in the least risky long-term securities, i.e., long-term sovereign bonds.

On the asset side, life insurers must have sufficient liquid funds available at all times to meet potential redemptions by policyholders. In order to settle these contracts as quickly as possible, life insurers must hold highly liquid bonds, often with relatively short maturities (less than one year). As a result, there is always a duration gap between liabilities and assets: the average duration of policyholders’ contracts, i.e., the average maturity of liabilities, is longer than that of assets. However, if this gap is too large in a low interest rate environment, it has a significant impact on the value of liabilities and assets.

During prolonged periods of low interest rates, securities held on maturing life insurance policies are reinvested in new bonds with lower yields: this is the reinvestment risk. As a result, life insurers’ margins are reduced because the yield on the new securities held falls, even though the guaranteed rates on life insurance contracts, especially older ones, are high. This results in capital losses, and the value of insurers’ liabilities may temporarily exceed that of their assets, threatening their solvency.

2.2 – Risk of mass policy surrenders

If policyholders believe that insurers can no longer guarantee sufficiently high rates on their euro-denominated contracts, they may decide to surrender their contracts en masse. A significant net outflow would force insurers to sell off their most liquid assets to settle their customers’ contracts and/or sell at a loss by disposing of their bonds before maturity, which would drive down the price of these assets.

These sales at a loss could then cause some insurers to go bankrupt, while generating systemic risk: if the volume of sales of the most liquid assets is significant, there is a risk of contagion for the most solid insurers via the deterioration in the quality of the assets they hold ( fire sale phenomenon).

2.3 – Risk of contagion to the entire system

In such a scenario, contagion effects would greatly increase the risk of bankruptcy even for institutions that were initially solvent. Furthermore:

– Once the first insurer goes bankrupt, contagion could spread to the entire financial sector through a widespread decline in the price of financial assets ( fire sales phenomenon);

– There is no system for protecting policyholders based on common standards within the European Union[5] ;

– Unlike banks, insurers do not have access to Central Bank liquidity in the event of difficulties;

– Life insurers are major investors and have a key impact on the real economy, through the financing of public debt by purchasing French sovereign bonds and meeting part of the financial needs of the private sector in which policyholders’ savings are invested.

However, this worst-case scenario seems to be the most disastrous and cannot be considered the most likely, even if the Japanese case should not be overlooked.

3 – What is the current level of risk?

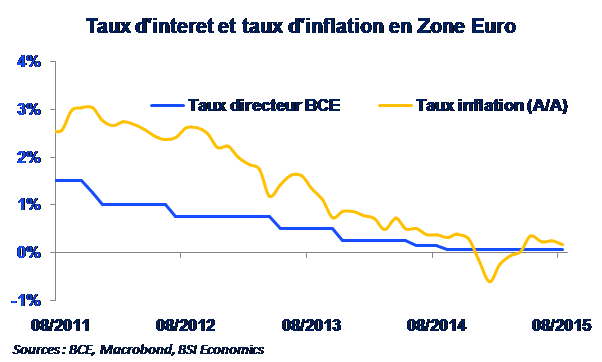

3.1 – The ECB’s policy of low interest rates

With the European Central Bank’s (ECB) quantitative easing (QE) policy in place until September 2016, the massive purchase of eurozone government bonds should keep downward pressure on bond yields. At the same time, the ECB is unlikely to raise its key interest rate given the still sluggish inflation in the eurozone. As a result, the period of low interest rates is likely to continue.

3.2 Strategies to contain risks

Three types of strategies are recommended for life insurers to prevent the current situation from degenerating into a Japanese scenario: extending the duration of their assets, seeking higher bond yields (high yield or nearinvestment grade) and/or investing in other asset classes.[6]or renegotiate the guaranteed rates on life insurance contracts.

With regard to the first strategy, as long as there is no massive redemption of life insurance contracts, there is no risk of outflows leading to a reduction in asset duration. On the contrary, figures for 2014 and 2015 in France show that life insurance is still the preferred way for French people to invest their savings[7].

The second strategy, which consists of seeking higher returns, could, however, be made more difficult by the Solvency II regulations, which require insurers to have significant capital reserves in order to hold securities that generate higher returns.

With regard to the latter strategy, French legislation allows life insurers to lower the minimum guaranteed rates on pre-established contracts, provided that the insured is informed[8]. However, if this practice is not sufficiently transparent, it can lead to complications if the insured party feels aggrieved. Furthermore, such a practice could prove dangerous if it became widespread and led to a mass surrender of policies by insured parties unhappy to see the return on their investment reduced further.

3.3 Risks that appear to be under control in France

In France, the situation appears less worrying than in Germany, the Netherlands, or Norway, as the duration gap between liabilities and assets is not yet too concerning, being less than five years for a guaranteed rate of around 1% according to Moody’s.

In addition, insurers have reserves[9]which they are already drawing on to offer higher returns than they should. These reserves are all the more essential as they currently guarantee the stability of the life insurance sector by maintaining returns at acceptable levels. If these reserves were to be depleted and the low interest rate environment were to continue, a Japanese scenario would be much more likely to unfold.

In Japan, the insurers that survived the crisis of the late 1990s were those with a diversified portfolio of activities (savings, pensions, life and non-life insurance, health insurance, unit-linked and euro funds, etc.), which seems closer to the model of French insurers.

Conclusion

With a prolonged period of low interest rates, the return on euro funds is bound to decline in the coming years. However, this will probably not be enough to ensure their stability, and the Japanese scenario should not be considered an extreme case.

The highly probable prolongation of the period of low interest rates and the low yields on bonds should prompt the supervisory authorities and life insurers to take decisions to protect themselves so as not to threaten the stability of the financial system.

Appendix: Overview of life insurance

Life insurance is primarily a long-term savings product that can be used to finance projects, invest for retirement, or grow savings. What matters for life insurance is the date it is taken out. From that date, it is possible to make regular or temporary payments and, in the event of withdrawal, to benefit from varying levels of taxation.[10]applies to the amount withdrawn (particularly advantageous tax exemptions apply when a life insurance policy is held for more than 8 years).

There are currently two types of life insurance[11] :

1. Single-support policies: these are euro fund policies, i.e., bond investments with no risk of capital loss and a guaranteed minimum annual rate of return. With this type of policy, returns are stable and highly secure.

2. Multi-support contracts: these are divided between euro funds and unit-linked funds, the latter being investments mainly in equities, equity funds or high-yield bonds. Unit-linked funds carry more risk in return for a potentially higher return.

Sources: French Prudential Supervision and Resolution Authority (2015)

Notes:

[1] This is a bond investment with no risk of capital loss and a guaranteed minimum annual rate of return. However, it may contain a small portion of real estate or equity investments, up to 10% or more of the total investment, in order to boost returns.

[2] Nearly 80% of the total outstanding amount, or more than €1.2 trillion.

[3] See the comments made by Christian Noyer, Governor of the Banque de France, in a statement on October 28, 2014 http://www.agefi.fr/articles/christian-noyer-veut-une-baisse-des-taux-des-contrats-d-assurance-vie-1336710.html.

[4] International Monetary Fund (IMF), (2015), » European Life Insurers: Unsustainable Business Model , » Reinout De Bock, Andrea Maechler, and Nobuyasu Sugimoto.

[5] In France, the guaranteed amount is a maximum of €70,000 per contract and per insurer.

[6] This is impractical to implement in a single-support contract without increasing the costs associated with these assets and the risk, even though this life insurance compartment is intended to be risk-free.

[7] Although demand deposits recorded the highest inflows (more than €22 billion between January and July 2015), life insurance is the second most popular financial investment in terms of savings inflows, with unit-linked products even reaching record levels: 33% of total life insurance inflows in 2014, compared with 17% in 2013, and in 2015 unit-linked products are ahead of euro-denominated funds.

[8] In accordance with Article A 132-1 of the Insurance Code.

[9] Each year, insurers set aside provisions for profit sharing (PPB) which they can draw on so that the returns achieved plus this PPB reach at least 85% of the financial returns that the Insurance Code requires them to pay to policyholders.

[10] If the life insurance policy is surrendered before four years, the interest is taxable and subject to a flat-rate withholding tax of 35%, and 15% for surrender between four and eight years. After 8 years for a withdrawal, above an income of €4,600 for a single person (€9,200 for a couple), interest is subject to a flat-rate levy of 7.5% or is included in taxable income.

[11] Euro-growth life insurance contracts could have been added to this list, but so far they are very rare. They are complex, offering capital guarantees for a minimum holding period of 8 years and with the possibility of building up a variable portion of diversified securities.

References:

– Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution (ACPR), (2015), » Monitoring of the collection and investments of the 12 leading life insurers at the end of December 2014 . »

– AXA IM, (2015), » Insurers in a low interest rate environment, » Eric Chaney.

– BSI Economics, (2013), » Euro Funds of Life Insurance Companies , » Allouche Jordan.

– BSI Economics, (2015), » Solvency II, securitization, and financing of the French economy (1/2), Chalendard Romaric.

– BSI Economics, (2015), » Solvency II, securitization, and financing of the French economy (2/2) , » Chalendard Romaric.

– BSI Economics, (2015), » German bond yields move away from negative territory , » Moussavi Julien.

– International Monetary Fund (IMF), (2015), » European Life Insurers: Unsustainable Business Model , » Reinout De Bock, Andrea Maechler, and Nobuyasu Sugimoto.

– Moody’s, (2015), “European Insurers face credit-negative QE program.”

– RBS, (2015), « German lifers are hurt badly by lower interest rates but are far from immune to a selloff, » Mary-Dauphin Clement.