Summary:

– Changes in unit labor costs are a necessary but not sufficient indicator of an economy’s cost competitiveness and price competitiveness.

– However, it is essential to put this change into perspective by referring to the level of unit labor costs in order to fully measure a regain in competitiveness.

When the concept of cost competitiveness is mentioned, the first thing that comes to mind is « wages. » A country is considered competitive when wages are low, and conversely, uncompetitive when wages are too high. But this reasoning is limited because (1) the concept of competitiveness is linked to two other inseparable parameters, namely hourly labor productivity and the number of hours worked, and (2) the definition of « wages » used is gross wages (net wages + social security contributions paid by the employee) plus employer contributions.

Let’s take an example. Suppose there is a country A where the average employee salary is €1,500 net per month, and a country B where the average employee salary is €2,500 net per month. In which country would you set up your business? It is impossible to answer this question without further details on, at a minimum, (1) the hourly productivity of employees in each country, (2) the number of hours worked by employees in each country, and (3) the various tax burdens on labor. If employees in country A have low productivity and labor taxation is high, then country B may be a better option.

The OECD offers a more comprehensive definition of unit labor costs, which « measure the average cost of labor per unit produced. They are equal to the ratio of total labor costs to output volume or, equivalently, the ratio of average labor costs per hour worked to labor productivity (hourly output). »

The evolution of unit labor costs as a sign of renewed competitiveness

A first graph, published at the end of July 2013, is provided by the IMF to illustrate the mechanism that would lower the evolution of unit labor costs: productivity growth must exceed the growth in hourly labor costs. The two countries studied are France and Germany over the period 1991-2008. The analysis focuses on changes in competitiveness relative to a common base of 100 in 1990. The comparison is therefore based on changes rather than the level of competitiveness in each country.

In France, wages have increased on average at the same rate as productivity (see the two rising red curves), resulting in stable unit labor cost growth since 1991, with a very slight increase since the 2000s.

In Germany, productivity has increased at the same rate as in France, but real labor costs have fallen since the early 2000s with the Hartz reforms (for more information on the Hartz laws in Germany, see http://www.bs-initiative.org/index.php/analyses-economiques/item/148-la-reforme-du-marche-du-travail-allemand-un-modele-reellement-seduisant-pour-le-reste-de-l%E2%80%99europe), resulting in a sharp decline in unit labor costs over the past decade.

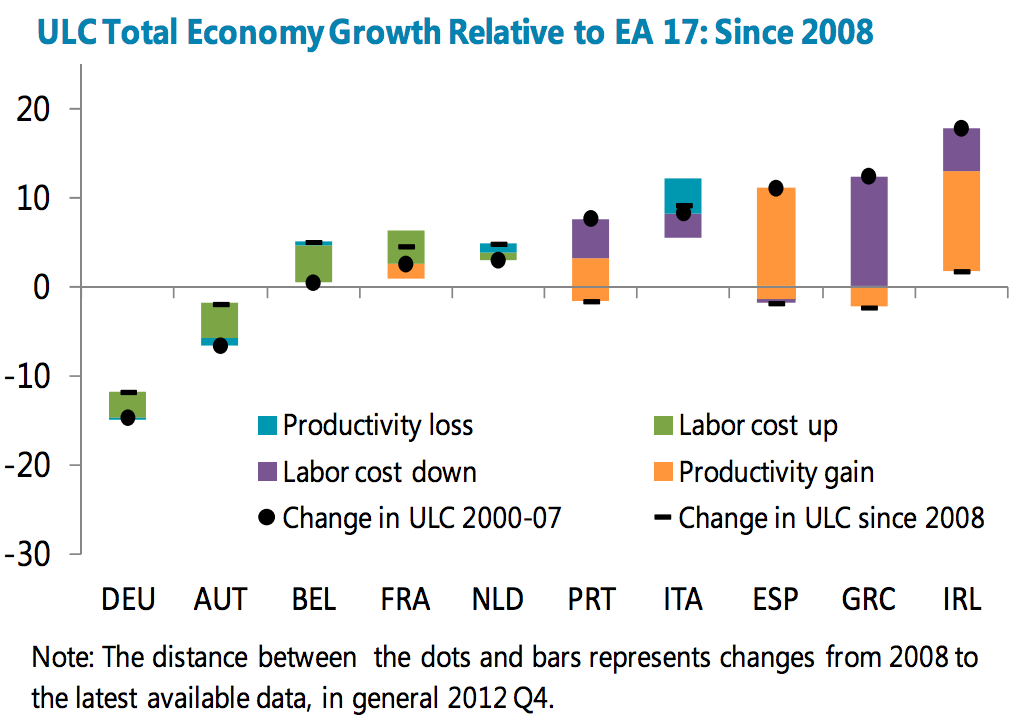

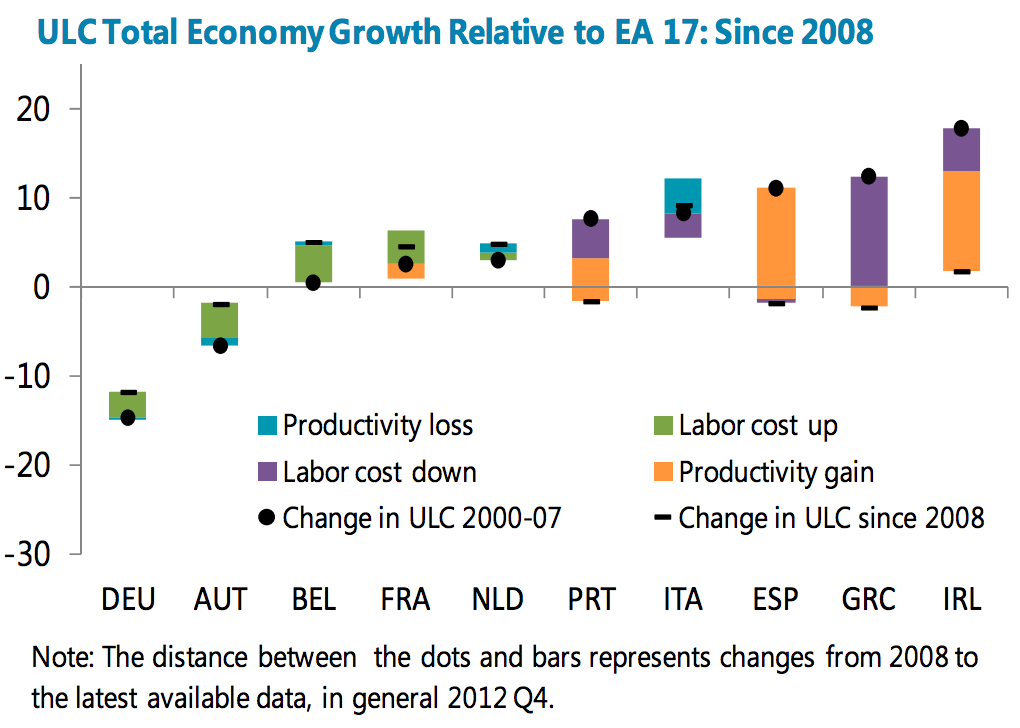

A second graph provides a comparative analysis of the eurozone countries. It distinguishes between the evolution of unit labor costs over two periods: from 2000 to 2007, and from 2008 to 2012.

Over the period 2000-2007, Germany and Austria (« DEU » and « AUT » in the graph) were the only two countries to experience a decline in unit labor costs (in the graph, the black dot is therefore below 0 – the trend is negative). However, these countries are among the last to have an AAA rating on their sovereign debt. Conversely, the countries currently in difficulty in the eurozone (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain) all experienced a sharp rise in unit labor costs over the period 2000-2007. This was due to a decrease in their unit labor costs through an increase in productivity (e.g., in Spain) or a freeze or even a decrease in wages (e.g., in Greece).

A decline in unit labor cost variation is not necessarily good for an economy, even if it is a sign of renewed competitiveness. This is the case in Greece, where recessionary effects linked to internal devaluation have been observed. On the other hand, an increase in real hourly wages can be offset by a proportional increase in productivity. This effect has been observed in France following an increase in the minimum wage slightly above inflation or following an increase in social security contributions. In any case, what is important is not only the change in unit labor costs but also their level. In short, while Germany has gained competitiveness since 2000 and Italy has lost competitiveness, there is no guarantee that German unit labor costs are more attractive than Italian unit labor costs.

The need to analyze unit labor costs in terms of level

An analysis by Patrick Artus shows that two factors determine an effective comparative analysis of the competitiveness of each country in the eurozone: (1) the level of unit labor costs based on real exchange rates at the time of the euro’s creation, and (2) the dynamics of these unit labor costs since 1999, with a focus on the existence or absence of countervailing forces capable of stabilizing them.

Thus, the most competitive countries (in terms of level, not variation) are currently Portugal, Greece, and Spain. Above all, low competitiveness is observed in France given (1) the absence of a stabilizing force, (2) an overvaluation of the real exchange rate, and (3) the level of production range.

Conclusion

Unit labor costs can be used to estimate a country’s cost competitiveness and, indirectly, its price competitiveness. However, it should not be forgotten that price analysis is insufficient and that it is therefore essential to consider non-price competitiveness (brand image, innovation, product quality, product range).

Reference:

– OECD statistics, » Key economic indicators «

– Natixis, « Cost competitiveness of eurozone countries: initial situation at the creation of the euro, subsequent dynamics, existence or absence of pullback forces, » Flash Economie, February 15, 2013, No. 155.

– International Monetary Fund, « Euro Area Policies – 2013 Article IV Consultation, » IMF Country Report No. 13/231, July 2013.