⚠️Automatic translation pending review by an economist.

Usefulness: The socioeconomicenvironment could determine the intensity of the effects of a crisis, as well as the ability to cope with it. Consequently, it is extremely important to have thorough crisis management planning in order to respond appropriately to the pre-existing reality, minimizing its adverse effects.

Summary:

-

The world is currently facing the Covid-19 health crisis, which has already demonstrated its destructive power from both a medical and socioeconomic perspective.

-

In Latin America, a singular impact can be expected, as the region presents a series of economic and social paradoxes.

-

In addition to numerous economic and social vulnerabilities, the region still has extremely fragile social protection systems.

-

The lack of planning hinders decision-making and leads to increased fiscal and social costs.

-

Given its economic fragility, the financial and budgetary challenges facing the region are undeniable. However, the need for a Latin American model to tackle the crisis is clear.

In 2020, the world is facing the Covid-19 health crisis, which has had a very negative impact so far, both from a socioeconomic and public health perspective. For the most vulnerable populations, which are very numerous in developing countries such as those in Latin America, the potential for these effects to multiply is predictable. Coping with the crisis is a real challenge for their governments.

The disease will undoubtedly have a singular impact in Latin America, a region that is already very fragile due to several socioeconomic factors. To understand the reasons for this vulnerability, we must first look at the context in which the region finds itself.

Economic environment

Over the past decade, Latin America has experienced multiple crises. Despite a rapid recovery from the 2008 recession, Latin Americans appear to be trapped in a situation of heavy dependence on exports of raw materials, particularly to the Chinese market. Today, with one of the worst economic performances on the planet in terms of GDP growth (0.1% in 2019), the region is suffering greatly from successive fluctuations in commodity prices and the slowdown in the Chinese economy. Having failed to implement a more inclusive fiscal policy that would enable them to change their economic model, which is focused almost exclusively on exports, Latin Americans now find themselves highly vulnerable to external shocks.

Faced with economic stagnation and successive public deficits, austerity policies have been implemented in many countries in the region. In addition, Latin America has been affected by several phenomena: inflationary movements (Argentina, Venezuela), loss of consumer purchasing power (Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela), budget cuts to social protection systems (Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico) and corruption scandals (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Peru). All these events have led to a wave of social unrest, particularly in South American countries such as Colombia, Chile, Bolivia, and Ecuador. Venezuela is experiencing an « apocalyptic » situation with its presidential crisis, Argentina is facing a recession, and the Latin American giants, Brazil and Mexico, are experiencing a slowdown in growth.

Economic and political fragility, as well as the lack of structural reforms since the golden age of economic growth in the 2000s, are now causing significant uncertainty in Latin American markets, preventing the region from recovering. The malaise will be even greater with the arrival of the coronavirus in the region, which seems destined for recession this year (in April, the International Monetary Fund predicted an average GDP contraction of 5.2% in Latin America and the Caribbean for 2020).

Social environment

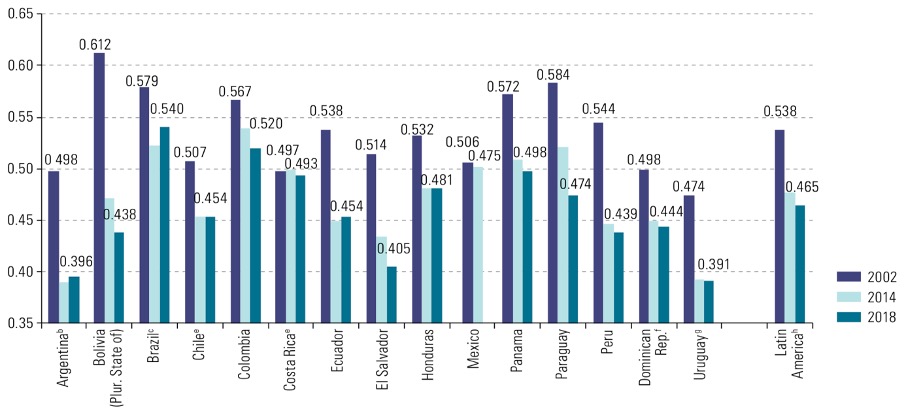

The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) Human Development Report 2019 identified Latin America as the region with the highest income inequality in the world. The richest 10% of the population earns a larger share of income than in any other region of the world (37%), while the poorest 40% earns the smallest share (13%). Furthermore, according to the 2019 Social Panorama of Latin America produced by the Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLAC), although income inequality fell significantly between 2002 and 2014, this trend slowed from 2015 onwards (Figure 1). There has also been a decline in poverty reduction in the region since 2015, with nearly one-third of the population living below the poverty line. A large number of people also continue to live in precarious housing conditions, such as in favelas, where there is overcrowding and poor access to basic services such as electricity and sanitation, with 5% and 35% of the population respectively lacking access to these services.The impact of the pandemic is therefore likely to be even greater, given that these populations are more vulnerable and more exposed to the spread of the virus.

Graph 1

Latin America (15 countries): Gini Inequality Index, 2002-2018

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLAC)

According to the latest reports from ECLAC and the International Labor Organization, unemployment and informality are another major concern in the region. While unemployment reached 8.1% at the end of 2019, the informality rate has continued to grow in recent years due to weak economic growth. Today, more than half of workers (53%) are employed in the informal sector, demonstrating the high degree of uncertainty and precariousness in the labor market. Because of this reality, a major challenge in the region is the social protection of workers, since the majority do not contribute to social security and therefore do not have access to these benefits. The current crisis is expected to further aggravate the situation in the Latin American labor market, particularly for informal workers, with tensions likely to drive up unemployment rates.

All this in an environment where health and social protection systems are fragile and vulnerable. In many Latin American countries, these systems rely heavily on private health care, while public services are limited. The latter are financed by direct state resources rather than by sustainable contribution and mutualization systems. They are therefore highly dependent on and subject to the economic and financial circumstances of the states. Historically very fragile, these health systems have suffered the serious consequences of numerous budget cuts resulting from the austerity policies that followed the Latin American economic and social crisis of the 2010s. In addition, the region is still facing two simultaneous epidemiological challenges that are already straining healthcare systems: the coronavirus pandemic, which is growing exponentially, and the worst dengue epidemic in its history.

Given all these factors, the debate remains the same: how can we minimize the damage already expected from this crisis? What weapons do states have to combat this threat and reduce its most harmful side effects?

From austerity to interventionism

The delay in acknowledging the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic largely explains why, from one moment to the next, governments around the world decided to set aside fiscal austerity and inject billions of dollars in aid to businesses and citizens to deal with the crisis. Evidence confirms that to mitigate the effects of a crisis of this magnitude, the state must take the lead. In order to prevent economic collapse and the breakdown of healthcare systems, the government is tasked with filling the void left by a paralyzed economy, ensuring its « vital » functioning until the epidemic can be brought under control. However, given the economic difficulties faced by Latin American countries in recent years, a series of challenges must be overcome in order to achieve this feat.

First, the capacity of Latin American economies to provide a stronger fiscal response to the crisis is likely to be quite limited. Many countries in the region have little fiscal space to absorb shocks. Furthermore, although there are significant regional differences, most of these countries are trapped by poor sovereign debt ratings. Indeed, with successive public deficits and highly fragile economies, Latin Americans would still pay the price for a negative financial solvency assessment. In an environment of mistrust toward emerging economies and a strong perception of default risk, countries in the region and their companies are likely to find it more difficult to raise funds on the international market, suffering from higher costs and less favorable payment terms. However, it is likely that some Latin American countries with better fiscal positions and good sovereign ratings will find it easier to implement fiscal stimulus policies, particularly Chile and Peru, which have already launched major plans to combat the crisis.

The restructuring of Latin American debt could provide some leeway to ease fiscal pressures, facilitating the implementation of measures to overcome the crisis. Currently, the Latin American Strategic Center for Geopolitics (CELAG) is conducting a global campaign with the IMF and other multilateral organizations (World Bank, IDB, CAF) to cancel part of the external sovereign debt of Latin American countries in the context of the global spread of the coronavirus. The initiative also provides for a restructuring of the remaining debt with private creditors. In addition, it is worth mentioning the current process of restructuring nearly $69 billion of Argentina’s debt, as well as Ecuador’s default. However, Ecuador was able to renegotiate the deferral of $811 million in interest payments on its external debt between March and August, enabling it to cope with the crisis.

In addition to fiscal policy, the region is also likely to face constraints in its monetary policy. Faced with slowing growth, governments can turn to their central banks to inject liquidity into the economy, lower interest rates, and facilitate access to credit. This is what we are currently seeing in several economies, notably in the United States, Europe, and Asia, in order to overcome the crisis. However, given the climate of mistrust and inflationary pressures affecting some Latin American countries, these measures have their limits. The most striking example is Venezuela. The country is currently experiencing hyperinflation (9,585.5% in 2019), which means that the government will not have the same scope to reduce rates in response to the crisis. Similarly, Argentina, which reached 53.8% inflation in 2019, will need to be vigilant. However, for countries with good foreign exchange reserves, such as Brazil, Peru, and Colombia, or Chile, where years of Chicago school thinking have given the Central Bank strong credibility, the room for maneuver will certainly be greater.

In an environment of capital flight, some countries may be tempted to raise interest rates. However, it seems unlikely that such policies will be effective and/or sufficient to reverse the trend and attract new investment. However, as concerns subside in developed economies, the real interest rate differential will have the potential to attract investors, particularly to certain emerging countries with developed capital markets (Mexico, Colombia, Chile, Brazil). Nevertheless, this attractiveness will only hold if inflation levels remain low. Thus, the major monetary challenges in Latin America will be precisely to be able to inject liquidity without causing inflation to rise, finding ways to sterilize central bank interventions.

It will therefore be particularly important to ensure that countries have sufficient foreign currency liquidity to avoid a liquidity crunch, especially for those Latin American economies with large current account deficits and a shortage of foreign currency. One solution would be to increase the number of swap agreements with the US Federal Reserve or the European Central Bank. Furthermore, the recovery in activity in China, coupled with low oil prices, could benefit countries in the region, particularly mineral producers, helping to prevent their current account deficits from widening further and reducing their excessive financing needs in 2020. However, this effect would be mixed for major Latin American oil producers such as Ecuador and Venezuela, which are still suffering greatly from losses in the energy sector. In addition, capital controls could temporarily have a legitimate place in any political regime in the region, reducing net capital outflows and avoiding successive currency and asset depreciation. This would facilitate the continuation of expansionary monetary policies to support the economy.

However, the current crisis would be yet another factor highlighting the urgency of implementing structural reforms in the region in order to reduce its vulnerability to external shocks and promote an environment for foreign direct investment in non-commodity sectors, ensuring a less volatile flow of capital. To achieve this, the degree of protection of local markets would need to be rethought, and development strategies focused on the dissemination of investment zones and special trade regimes (free zones and technology development zones) could also be explored.

Conclusion

In Latin America, a dangerous scenario is emerging that could cause a significant number of casualties. In light of this, the destructive power of the coronavirus must not be reduced to medical assessment alone, but must also be analyzed in the context of the socioeconomic conditions in which the pandemic is developing.

In this turbulent environment, the lack of planning hinders decision-making and leads to increased fiscal and social costs. There is no doubt that governments in the region need effective crisis management centers capable of assessing the best way to implement measures to minimize the adverse effects of the pandemic, thereby avoiding economic and health collapse. The financial and budgetary difficulties facing these countries are undeniable, but it is imperative to create a Latin American model to overcome this crisis.

References

Ambito (2020) Piden la condonación de la deuda externa de todos los países de América Latina. Ámbito Financiero. Available at: https://www.ambito.com/economia/deuda/piden-la-condonacion-la-deuda-externa-todos-los-paises-america-latina-n5091824

Carneiro, D.D., WU, T. Y. H. (2004) External accounts and monetary policy. Rev. Bras. Econ. vol.58 no.3 Rio de Janeiro July/Sept. 2004. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-71402004000300001

CELAG (2020) It is time for debt forgiveness for Latin America. Available at: https://www.celag.org/la-hora-de-la-condonacion-de-la-deuda-para-america-latina/

CEPAL. (2018) Statistical Yearbook of Latin America and the Caribbean 2018. Available at: https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/44445-anuario-estadistico-america-latina-caribe-2018-statistical-yearbook-latin

(2019) Social Panorama of Latin America 2019. Available at: https://www.cepal.org/pt-br/publicaciones/45090-panorama-social-america-latina-2019-resumo-executivo

Cheyvialle, A. (2019) Anger grows in a sluggish Latin America. Le Figaro. November 2019. Available at: https://www.lefigaro.fr/conjoncture/la-colere-enfle-dans-une-amerique-latine-au-ralenti-20191128

Godoy, D., Estigarribia, N., Caetano, R. (2020). Quem vai salvar a economia do coronavírus? Rev. Exame. March 2020. Available at: https://exame.abril.com.br/revista-exame/quem-vai-salvar-a-economia/

ILO. (2019) Panorama Laboral 2019. América Latina y el Caribe. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/americas/publicaciones/WCMS_732198/lang–es/index.htm

IMF (2020). World Economic Outlook April 2020. Available at: https://www.imf.org/fr/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/04/14/weo-april-2020

Lafuente, J. (2020) Latin America faces coronavirus crisis amid political tensions and economic fragility. El Pais. March 2020. Available at: https://brasil.elpais.com/internacional/2020-03-18/america-latina-enfrenta-crise-do-coronavirus-em-meio-a-tensoes-politicas-e-fragilidade-economica.html

Lazarini, J. (2020) Coronavirus: Moody’s says impact on Brazil remains severe. Suno Research. March 2020. Available at: https://www.sunoresearch.com.br/noticias/coronavirus-moodys-impacto-no-brasil/

Lissardy, G. (2020) Why Latin America is the ‘most unequal region on the planet’. BBC News. February 2020. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-51406474

Napolitano, G. (2017) Not even commodities saved Latin America’s economy. Rev. Exame. August 2017. Available at: https://exame.abril.com.br/blog/primeiro-lugar/nem-as-commodities-salvaram-a-economia-da-america-latina/

UNDP. (2019) Human Development Report 2019. Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr_2019_pt.pdf

Sallas, O. S. (2012) The Impact of the Global Economic Crisis on the Americas: The China Effect. ParlAmericas, Plenary Assembly, August 30 – September 1, 2012. Panama City, Panama. Available at: https://parlamericas.org/uploads/documents/PA9%20%20Solis%20Fallas% 20%20Article%20-%20POR.pdf

UNCTAD (2020) UN calls for $2.5 trillion coronavirus crisis package for developing countries.Available at: https://unctad.org/en/pages/newsdetails.aspx?OriginalVersionID=2315

Ventura, C. (2020) Coronavirus: the situation in Latin America. Iris. Analyses. March 2020. Available at: https://www.iris-france.org/145572-coronavirus-etat-des-lieux-en-amerique-latine/