Summary:

– Cognitive biases lead to overconfidence among some individual investors, which contributes to lower returns on their stock portfolios.

– These biases, through the phenomena of self-attribution and individualism, are characterized by an increase in transactions and volatility for these investors.

– In countries where individualism is strong, these declines in returns are more significant, and in the United States, men’s portfolios tend to underperform those of women.

– The risk of momentum effects can be very dangerous in some cases and undermine financial stability.

What investor has not dreamed of beating the market based on their own analysis of stock prices? It is certainly not impossible to achieve consistent capital gains. But beyond the technical aspects of modern finance, for this to happen, an investor must also be able to anticipate certain market movements based on public information, identify companies that are going to perform well, and take positions to hedge without reducing their potential gains.

This is no easy task, and it is best not to succumb to overconfidence or any other risky behavior. From self-attribution to momentum effects and individualistic biases , there are many reasons to believe that consistently beating the market is a sweet illusion.

Overconfidence

Behavioral finance, a relatively « young » field in economics, analyzes investment strategies based on various aspects, which can be economic, sociological, or psychological. The aim of this field is to identify the correlations between investor behavior, their strategic choices in managing their stock portfolios, and the performance of those portfolios.

A large body of literature has highlighted the existence of several cognitive biases that lead investors to make suboptimal decisions in terms of portfolio management. Among these biases, self-attribution and individualism are two behaviors that can lead to overconfidence.

Self-attribution (Zuckerman, 1979, Scheinkman, 2003) consists of attributing all forms of success to oneself and denying any responsibility for failures. As a result, individuals base their choices solely on personal information and underestimate all other sources of information (in this case, all information is public and not private, in which case it would constitute insider trading, punishable by imprisonment). Individualism can also contribute to overconfidence; Hofstede’s work on the subject shows that in certain societies with a strong individualistic culture (the United States, for example), individuals tend to be more optimistic, focusing on their own skills and thus estimating their abilities to be above average (Markus and Kitayama, 1991).

Increased trading volume + high volatility = lower returns

The implications of this type of behavior are quite varied and generally contribute to reducing the returns on the portfolios of overconfident investors. Overestimating one’s abilities can lead an individual to overestimate the expected return on their investments, which will then lead them to want to compensate for this lower performance by making new transactions. The trading volume of this type of investor therefore tends to be quite high. The higher the volume, the higher the transaction costs, without any logic of portfolio diversification.

If a large number of investors (representing a significant volume of total transactions) act in this way, there is a risk of generating high volatility (mainly due to repeated purchases and sales of the same asset class) in the returns on the securities traded, which is an additional threat to both the transmission of information and the overall return on equity portfolios containing these securities.

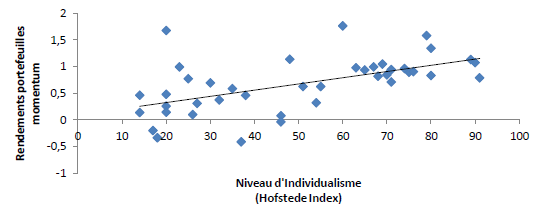

Several studies (Barber and Odean, 1998 and 2001) show that in the United States, men are more inclined than women to overestimate their abilities, develop cognitive biases, and believe they can easily beat the market. Overall, according to these studies, male portfolios underperform female portfolios. These results are even more pronounced in countries with a high degree of individualism (Titman and Wei, 2010), with countries such as the United States, England, Australia, and Canada at the top of the ranking. France, Germany, and Sweden are less affected by this problem, but their results remain fairly « average » compared to countries such as Japan, Israel, and Argentina.

The momentum effect: the real danger!

Until now, we have mainly focused on individual or isolated investors who do not necessarily have easy access to all the information or who do not necessarily have the expertise of specialists and trading room operators (even if no analyst is immune to behaviors that lead to overconfidence!). However, certain attitudes, even among experts, can threaten the financial markets: momentum effects.

The momentum effect is defined as the tendency for securities that have performed well (or poorly) in the past to continue to perform well (or poorly) in the future. The momentum strategy consists of buying securities that have outperformed over the last 3 to 12 months and selling those that have underperformed. The first article to provide formal proof of its existence and profitability on the US market was published in 1993 by Titman. Since then, other articles have revealed that this was also the case in Europe (Rouwenhorst, 1999 and Griffin, 2003). However, momentum strategies only generate returns in the short term (less than one year).

Sources: Amira Bellar & Victor Lequillerier, MBF, BSi-Economics

This effect and the strategy that results from it are closely linked to overconfidence, characterized by self-attribution bias or individualism (Hirschleifer, 1998). As a result, the momentum effect can lead investors, whether experts or not, down the path of chartism, which consists of establishing a portfolio management strategy with a short-term vision by following price rises and falls. The race for returns (annual return, adjusted for the risk of momentum strategies , of 12.83% over the period 1965–1989 in the United States according to Titman) and rising prices take precedence, and investors’ choices no longer necessarily refer to economic fundamentals, or only very marginally. This is all the more dangerous given that all empirical studies on the subject show that momentum strategies reverse in the medium term (negative returns beyond one year) and gradually erode the expected return of the momentum portfolio .

This behavior is all the more dangerous as it can contribute to unexpected, self-perpetuating price increases and, in the worst case, to the creation of bubbles on certain assets, in a context similar to what Minsky calls « the paradox of tranquility. » Not all price increases turn into bubbles (fortunately!), but it is very difficult to know when a bubble is forming. And since « it is better to be wrong with the market than right against the market, » some increases are self-perpetuating and suit all investors until a bubble appears, and it is often only once it bursts that its presence is detected.

Conclusion

Without even mentioning market efficiency hypotheses (which are probably no longer really relevant to the reality of financial markets, even if there is no consensus on the issue), continuously beating the market is neither rational nor conceivable. Cognitive biases contribute to fueling the mystical beliefs of some, but as long as they are the only ones paying the consequences of their actions, the stability of the financial system is not threatened. However, the existence of mimetic effects, leading to momentum effects, can be feared, and unfortunately, few solutions are currently emerging to observe or manage this type of risk.

Bibliography

– Thomas Renault, « Boys will be boys: overconfidence and irrationality among men in finance, » Captain’Economics, http://www.captaineconomics.fr/actualite-economique/item/343-exces-confiance-irrationalite-homme-investissement

– Andy C.W CHUI, Sheridan TITMAN, and K.C. John WEI,« Individualism and Momentum around the world,« The Journal of Finance, 2010.

– Jegadeesh, Narasimhan, and Sheridan Titman, « Returns to buying winners and selling losers: Implications for stock market efficiency, « Journal of Finance 48, 65–91, 1993.

– Barber, Odean, “Boys Will Be Boys: Gender, Overconfidence, And Common Stock Investment, » 2001.

– Rouwenhorst, K. Geert,“International momentum strategies,” Journal of Finance, 1998.

– Griffin, John M., Xiuqing Ji, and J. Spencer Martin,“Momentum investing and business cycle risk: Evidence from pole to pole,” Journal of Finance, 2003

– Daniel, Kent, David Hirshleifer, and Avanidhar Subrahmanyam,“Investor psychology and security market under- and overreactions, ” Journal of Finance, 1998.

– Odean, Terrance,“Volume, volatility, price, and profit when all traders are above average,” Journal of Finance, 1998.

– Gervais, Simon, and Terrance Odean,“Learning to be overconfident,”Review of Financial Studies, 2001.

– Scheinkman, Jose, and Wei Xiong,“Overconfidence and speculative bubbles,” Journal of Political Economy, 2003.