Summary:

-Shadow banking refers to all financing activities outside the traditional banking sector. In China, it has become a major source of financing for the economy in just a few years.

-Its recent development in China can be explained by a combination of factors: abundant savings, intense investment, attractive returns, and diffuse government guarantees.

-Shadow banking is particularly vulnerable to the real estate sector, which is showing signs of slowing down.

Just over a year ago, in January 2014, a high-profile default loomed in Chinese shadow banking. Customers of ICBC, China’s largest bank, had been warned that the investment with the magical name « Credit Equals Gold#1 » would default at the end of the month due to the financial difficulties of the mine in Shanxi that it had been used to finance. But a few days before the expected default date, the mine found a providential investor whose identity was not revealed, and the default was avoided. Was this missed default indicative of the importance and difficulties of shadow banking in China?

Shadow banking refers to all financing activities outside the regulated banking sector. In China, it has become a major source of financing for the economy in just a few years (30% of household, non-financial corporate, and public debt), with credit growth twice as high as that of the traditional banking sector (+36%/year on average since 2007, compared to +18% for the banking sector).

What are its origins? What forms does it take? What are the risks to which it is exposed?

1 – What are the origins of Chinese shadow banking?

Shadow banking is fueled by savings, a salient feature of the Chinese economy. At more than 50% of GDP, China’s gross savings stock is among the highest in the world.[1]. However, economic and financial literature on shadow banking agrees[2on the decisive role of demand for risk-free assets in the emergence of this mode of financing. The idea is as follows. The traditional banking sector is a source of risk-free investments (deposit guarantees), but these are limited. When savings seeking risk-free investment exceed what can be absorbed by the traditional banking sector, the excess savings are absorbed by shadow banking through financial intermediaries (SPVs – Special Purpose Vehicles) whose assets consist of a diversified portfolio of risky loans purchased from banks. The liabilities consist of debts, some of which are theoretically risk-free, given that in the event of losses on the assets, these are the last to absorb them (tranching). While in the United States this risk-free status was achieved in theory through tranching, in China the absence of risk stems from the real or perceived guarantee of the state, given its pervasive presence in the economy. The originality of Chinese shadow banking, which is also one of its paradoxes, is the presence of investments considered risk-free and offering interest rates of around 10%.[3].

Shadow banking really took off in China during the 2008 credit crunch. Some companies with cash reserves realized that it was more profitable for them to lend their cash than to finance productive investment, giving rise to non-bank financial companies such as Sunny Loan Top. The year 2008 also saw the launch of a stimulus plan under which local authorities were encouraged to borrow to finance infrastructure spending. Initially, local authorities, through their financing companies, turned to state-owned banks. Subsequently, when state-owned banks were caught up in regulatory constraints on capital, local authorities turned to trust companies, one of the main forms of Chinese shadow banks.

2 – What forms does Chinese shadow banking take? The case of the « Credit Equals Gold » product.

Chinese shadow banks take three forms:

– Trust companies (representing nearly 40% of shadow banking): this is the largest and fastest-growing channel of financing. These companies finance the real estate sector, the mining sector, and local government financing companies. They are marketed directly to wealthy investors and indirectly to bank customers in the form of insurance and wealth management products. Interest rates are around 10%.

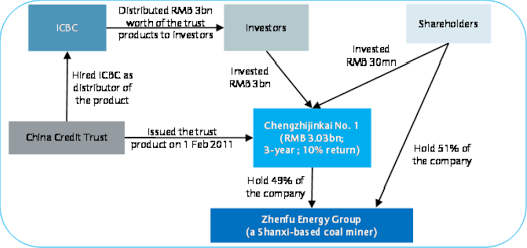

The product « Credit Equals Gold #1 » (interest rate of 10% per annum over three years) is one example (Figure 1). Instead of obtaining financing from a bank, the shareholders of the mining company Zhenfu Energy Group created a trust company, China Credit Trust, whose securities were marketed by ICBC. As the latter is a state-owned bank, the securities appeared to be implicitly guaranteed by the state. With the funds raised, China Credit Trust acquired a stake in the mining company. The original shareholders of the mining company had undertaken to buy back the shares of China Credit Trust before the Credit Equals Gold product matured. However, Zhenfu Energy Group faced a series of lawsuits concerning illegal sources of financing, resulting in the suspension of its projects and the inability of its original shareholders to buy back China Credit Trust’s shares. The default of Credit Equals Gold #1 was imminent, but at the last minute, an unknown investor enabled China Credit Trust’s investors to recover their investment.

Chart 1: « Credit Equals Gold #1 » or the financing of a coal mine that came close to bankruptcy

Source: Barclays, BSI Economics

– Non-financial companies (20%): these are large companies that take advantage of their relatively low financing costs to finance other companies. Due to restrictions on lending between non-financial companies, these types of loans are made through the traditional banking sector. In such a transaction, the lending company is exposed to the risk of default not by the bank, but by the borrowing company.

– Non-bank financial companies and others (40%): this category includes a wide range of companies, from financial companies such as Sunny Loan Top to rural cooperatives and peer-to-peer lending companies. This financing channel mainly concerns SMEs and individuals. Interest rates can reach several tens of percent.

3 – Towards a crisis in shadow banking? Key factors.

If Chinese shadow banking is complex, it is more because of the multitude of forms it takes than because of its risk engineering: unlike American shadow banking, which was based on risk diversification—now recognized as a « myth »[4]in financial theory[5]— and on numerous intermediaries, Chinese shadow banking represents for an investor a risk-taking via an intermediary on one or a few borrowers (see Credit Equals Gold #1), most often local authorities or companies linked to the real estate sector.

However, a number of indicators point to a downturn in the real estate sector, which represents (directly or indirectly[6]) 45% of the country’s debt, excluding the financial sector. In an economy where the financial difficulties of large companies rarely result in default, the first default by a Chinese real estate developer on its external debt (Kaisa, December 31, 2014) is indicative of the emerging difficulties in this sector. Its slowdown and overcapacity are more than evident in the statistics available for 40 major Chinese cities: the value of transactions in this sector fell by 14% (-33% in Beijing, -31% in Shenzhen) between April 2013 and August 2014, after an average annual increase of 26% over 10 years. In addition, the stock of unsold residential real estate appears to be well above historical averages.

The ability of Chinese local authorities to honor their debt is also becoming a source of concern due to the slowdown in the number of transactions in the real estate sector. Local authorities finance themselves through financing companies that allow them to issue off-balance-sheet debt. While some of these companies generate cash flow from their assets (e.g., residential buildings), others rely on collateral, such as a portion of land, or on an implicit guarantee from the local authority. Given that land sales account for a very substantial share (60% in 2013) of local government revenues, a crisis in the real estate sector would put pressure on local government budgets and make the land pledged as collateral illiquid or virtually illiquid.

Conclusion

Chinese shadow banking is almost the quintessence of China’s current growth model: massive investment in infrastructure and real estate, backed by massive debt. Given the state’s aversion not to risk but to defaults, the latter in shadow banking still remain largely in the shadows. With the reorientation of the growth model (less growth through investment and debt) and the Communist Party’s decision to give market mechanisms a « decisive » role, shadow banking could well emerge from the shadows, but without bringing sunshine.

References

-A Model of Shadow Banking, The Journal of Finance, August 2013.

-People’s Republic of China, country report, IMF July 2014.-People’s Republic of China, country report – IMF July 2014.

-Debt and (not much) deleveraging, McKinsey Global Institute, February 2015.

-The two conditions for the emergence of shadow banking, Natixis, April 2014.

-China’s Fiscal and Tax Reforms: A Critical Move on the Chessboard, Rhodium Group, July 2014.

-Financial Times.

Notes:

[1] The causes are complex, mainly economic (slower adjustment of consumption relative to income in a context of strong economic growth, for example) and institutional (poor access to consumer credit, for example).

[2] N. Gennaioli, A. Shleifer, R. W. Vishny, 2013, A model of Shadow Banking, The Journal of Finance.

[3] By way of comparison, the rate on bank deposits is capped at 3.3% and the inflation rate is around 1%.

[4]The creation of diversified loan portfolios that back the issuance of « risk-free » debt by shadow banks eliminates their exposure to borrowers’ intrinsic risk (i.e., risk resulting from events specific to them, such as divorce), but increases their exposure to systematic risk (i.e., risk that affects all loans, such as a recession) and, when extreme systematic risk is underestimated, increases systemic risk (risk of deterioration or paralysis of the entire financial sector).

[5] Brown, Gordon, 2010, Beyond the Crash: Overcoming the First Crisis of Globalization, Free Press, New York.

[6]Including sectors related to real estate and public debt that finances real estate projects.