Summary:

– The renminbi is playing an increasingly important role in the International Monetary System (IMS), thanks to China’s integration into global trade and the government’s efforts to internationalize it.

– However, obstacles still prevent it from becoming an international currency, notably financial markets that are not sufficiently open and developed.

– The emergence of the renminbi as an alternative to the dollar raises the question of a multipolar IMS.

The series of devaluations carried out by the People’s Bank of China during the summer of 2015 (three consecutive announcements on August 11, 12, and 13, resulting in a total devaluation of almost 3% of the yuan-dollar exchange rate) was presented by the authorities as a step towards liberalizing the Chinese exchange rate. This would be consistent with the authorities’ ambition to make the renminbi (the « people’s currency, » see note note from BSI Economics for the difference with the yuan) an international currency. The IMF will decide in October this year whether or not to include it in its SDR basket. These developments raise the question of a multipolar international monetary system (IMS).

1 – What is an international currency?

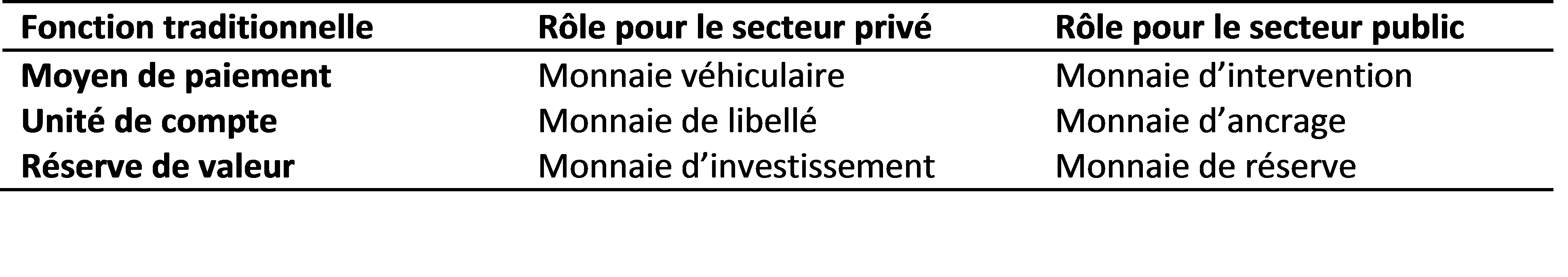

An international currency fulfills the three traditional functions of currency at the international level. This point was raised by Paul Krugman in 1991, who associates each of these functions with a role that an international currency fulfills for both the private and public sectors.

Source: Agnès Benassy-Quéré, International Economics, BSI Economics

– A currency is first and foremost a unit of account: it enables price transparency. An international currency is used to denominate international assets such as bonds or commodities, providing clarity for private actors such as exporters and importers. An international currency is also used by the public sector as a unit of account when the national exchange rate is pegged to its value.

– Currency also serves as a means of payment. An international currency fulfills this role when the private sector uses it to settle its international transactions.

– Finally, a currency is a store of value. Non-residents use an international currency for their investments. It serves as a store of value for central banks when they intervene in the foreign exchange market, in which case it is referred to as official reserves.

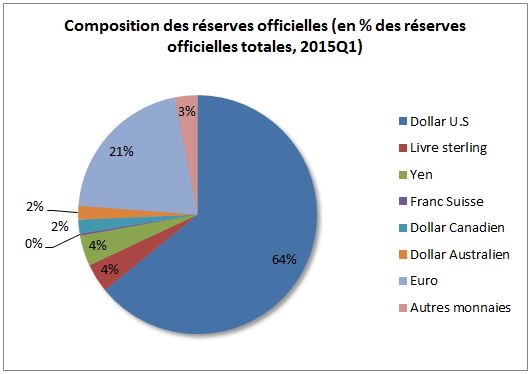

Since the end ofthe 20th century, the US dollar has fulfilled all these functions internationally and in a dominant manner. For example, it is used as the currency for oil and is involved in 87% of foreign exchange transactions.[i] In addition, 64.12% of central banks’ official reserves are held in dollars.

Sources: IMF, BSI Economics

2 – The role of the renminbi in the International Monetary System (IMS)

As China has gained weight in world trade and become a leading economic power, the place of the Chinese currency in the IMS has changed. This has been combined with a growing role for the country’s authorities, who have been seeking to promote its internationalization, particularly since the late 2000s.

China has become the world’s leading exporter of goods, and the share of its trade in goods with the rest of the world conducted in renminbi rose from 0 to almost 10% between 2010 and 2012, with the dollar remaining the most widely used currency for this purpose. [ii].

According to SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications), in January 2015 the renminbi became the fifth most widely used currency for international payments for the first time, behind the dollar, the euro, the pound sterling, and the yen [iii]. Two years earlier, it ranked as the 13th most widely used currency in the world, accounting for 0.63% of total international payments, compared with 2.34% today.[iv]

This leap in the renminbi’s position in the international monetary system follows the authorities’ desire to remove barriers to its internationalization. A turning point came in 2009, when they launched a pilot project (the Cross-Border Trade RMB Settlement Pilot Project) allowing a few cities and provinces to settle their exports and imports in renminbi with Macao, Hong Kong, and ASEAN countries. The scheme has now been extended to almost all Chinese trade. The liberalization of China’s capital account has also increased considerably, with financial institutions and then companies being able to issue renminbi bonds from Hong Kong ( Dim Sum bonds) since 2010. This has enabled the HSBC banking group and the multinational McDonald’s to issue Dim Sum bonds, whereas previously such transactions were reserved for Chinese and Hong Kong banks.

Subject to quotas that have been steadily expanded in recent years in terms of partner countries (Singapore, the United Kingdom, France, Qatar, and Luxembourg, for example) and amounts, certain investment transactions in renminbi are now possible. Once licensed by the authorities, institutions can invest from Hong Kong in the Chinese capital market ( RQFII quota) or in the interbank bond market ( CIBM quota).

Whereas previously the use of the renminbi outside China was very limited, these numerous initiatives reflect the government’s desire to increase its circulation beyond China’s borders and to increase the number of players using it for their international settlements. This is evidenced by the numerous swap lines ( enabling central banks in other countries to obtain renminbi liquidity) that the People’s Bank of China has established with foreign central banks in order to provide trading partners with renminbi to settle imports from China in that currency. Today, more than 30 central banks are involved in these swap agreements, including the central banks of the United Kingdom, Brazil, and Russia, as well as the European Central Bank.

3 – Towards a multipolar monetary system?

These advances in the internationalization of the renminbi do not obscure the fact that its convertibility remains highly restricted and far from a free trade regime. First, because the liberalization of China’s capital account is still partial, the purchase of assets by non-residents in renminbi is very limited (in terms of types of investment, amounts, etc.).[v], and inward FDI is limited by quotas and regulations. As a result, international demand for renminbi assets remains subject to these financial restrictions and capital controls, hindering its status as an international currency. The offshore renminbi market is limited and highly concentrated in Hong Kong. Added to this is the insufficient size and depth of domestic financial markets, which further reduces the renminbi’s ability to finance international trade and attract large-scale FDI. Finally, its use as a reserve currency is low because few central banks hold renminbi-denominated assets despite swap agreements.

Furthermore, the renminbi’s emergence as an international currency will also depend on its status as a vehicle currency for the private sector, and for the moment it remains far behind the dollar and the euro, which are used in the overwhelming majority of international transactions. The challenge will be to overcome the network effects enjoyed by these two dominant currencies, as the position of an international currency is self-perpetuating. The more it is used for transactions, the more the transaction costs associated with exchanging between two currencies are amortized, making it more advantageous to continue using it. This makes it difficult to compete with an established international currency.

These obstacles may delay the inclusion of the renminbi in the IMF’s SDR basket. The Special Drawing Right, created in 1969 by the IMF, is not a currency per se but is designed as a global reserve asset. It is a potential claim on the central banks of member countries that contribute a quota to the fund in exchange for a proportional allocation. A country in need of balance of payments financing can obtain currency from the basket in exchange for its SDRs, becoming a debtor to the IMF rather than directly to another central bank. The total allocation is set by the IMF according to reserve needs, the idea being to create a reserve asset that does not depend on any single issuing country. The value of the basket combines the relative weights of the dollar, pound sterling, yen, and euro, with the composition revised every five years. The inclusion of a new country depends in particular on its strong integration into world trade, a criterion met by China, but also on the free convertibility of its currency and the size and openness of its financial markets, which are more problematic for the renminbi.

The SDR represents a small share of global official reserves, but it has seen renewed interest since the 2007-2008 crisis, which created demand for an alternative to the dollar. In particular, in 2009, Zhou of the People’s Bank of China expressed his opposition to the current dollar-dominated monetary system and proposed the SDR as a viable alternative.[vi]This view has been widely echoed since then, notably by the UN in 2010. This renewed interest in the SDR and the potential inclusion of the renminbi in the basket reveals the contradiction between the multipolarization of the global economy and an international monetary system largely dominated by the dollar, a kind of new Triffin dilemma.[vii]. This refers to the incompatibility between the international reserve currency needs of the IMS and the internal needs of the issuing country, which is forced to run a current account deficit in order to provide the rest of the world with liquidity, thereby weakening confidence in its currency. The result is inevitable imbalances (such as the US current account deficit) and the predicted loss of the United States’ monopoly on the global reserve currency as its influence in a multipolar world declines.[viii]

We can therefore imagine that the international monetary system is in the process of aligning itself with the multipolarization of the global economy, where the dollar can no longer be the only key currency. The return of the SDR and the emergence of the renminbi may offer private and institutional investors alternative reserve currencies.

Conclusion

The renminbi’s status in the SMI has taken a leap forward with China’s integration into global trade and the authorities’ initiatives to promote its internationalization. Its accession to international currency status will require further liberalization of Chinese financial markets and could occur within 10 to 15 years. [ix], in an international monetary system that has become multipolar.

Notes:

[i] Agnès Benassy-Quéré, International Monetary Economics

[ii] European Central Bank, The International Role of the Euro, July 2013

[iii]http://www.swift.com/about_swift/shownews?param_dcr=news.data/en/swift_com/2015/PR_RMB_into_the_top_five.xml&lang=fr

[iv]http://www.swift.com/about_swift/shownews?param_dcr=news.data/en/swift_com/2015/PR_RMB_august_2015.xml&lang=fr

[v]I to (2011), “The internationalization of the RMB: Opportunities and pitfalls,” Council on Foreign

Relations, Washington DC.

[vi] Zhou (2009), « Reform the International Monetary System, » People’s Bank of China.

[vii]Fahri, Gourinchas, Rey (2011) Reforming the international monetary system, CEPR

[viii] Farhi, Gourinchas, and Rey (2011), « What Reform for the International Monetary System? »

[ix] Eichengreen (2011), “Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System,” Oxford University Press.