The FRENCH version follows the ENGLISH version below // Version française à la suite de la version anglaise

I thank Peter Stella and Jézabel Couppey-Soubeyran for feedback and insightful discussions. Opinions are my own.

Highlights:

– It is recognized by many economists that a negative interest rate is not a tool aimed at « inducing banks to lend more to households or companies » as (put simply) banks do not « lend out » reserves

– In the case of interbank loans, however, banks do « lend out » reserves

– I thus discuss the argument « a negative interest rate can induce banks to lend more to each other on the interbank market. »

– The argument appears mechanically invalid

– Only a larger corridor rate or a partial taxation of reserves system can lead to increasing interbank lending

Many economists argue that the ECB negative interest rate on banks’ excess reserves cannot in itself incentivize banks to lend more to households or companies (see Stella (2014) or Ducrozet (2015) eg). The core argument they advance (among others) is of a mechanical nature: banks do not « lend out » reserves when making a loan to a household or a company, thus it is incorrect to assert that banks could be subjected to such loan incentives with a tax on their reserves [1].

In the case of loans to other banks, however, banks do « lend out » reserves: when a bank makes a loan to another bank, reserves leave the lending bank’s account at the ECB (to go to the borrowing bank’s account). Thus, by making a loan to another bank, it is possible for a bank to escape the tax on reserves imposed by a negative interest rate. Does the ECB negative interest rate thus create an incentive for banks to lend more to each other? If this were the case, it would have positive effects on interbank market liquidity and thus potentially positive effects on the economy. Some economists suggest this could be a channel at work.

This post explains that this cannot be the case: there is no such mechanical effect whereby a negative interest rate on banks’ excess reserves results in incentives for banks to lend more to each other (part 1). However, it may be that a negative interest rate results in an increasing velocity of reserves on the interbank market in two particular cases (part 2): (1) if only the interest rate on banks’ excess reserves is lowered (larger rate corridor) and (2) if only a portion of excess reserves is subject to the negative interest rate (partial taxation of reserves). In these cases, the increasing velocity of reserves would not be the result of the negative rate: the same mechanism would be at work with a positive interest rate. Despite everything, we conclude that it is unlikely that the ECB resorted to (1) (larger rate corridor) last December or will implement (2) this month with the goal of increasing interbank market activity (conclusion).

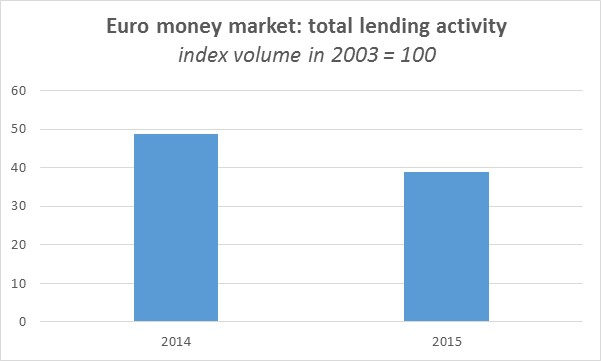

1. An invalid theoretical argument

Suppose that all banks’ excess reserves are taxed at an interest rate of 0.1% (thus the interest rate on the ECB’s deposit facility would be equal to -0.1%) and that the ECB’s refi rate (the rate at which banks can borrow from the ECB on a weekly basis) is +0.15%. Now suppose the ECB decides to lower its interest rates by 10 basis points: the excess reserves are now taxed at 0.2% and the refi rate now equals 0.05%. Banks with excess reserves are now taxed twice as much. The table below summarizes this scenario. According to the argument we initially referred to, banks would now like to lend more to each other given that their reserves are more heavily taxed. Does this really make sense? The answer is no: the focus should be on relative figures rather than absolute figures.

Let’s take two representative banks: Bank E, which has excessreserves, and Bank N, which needsreserves for liquidity purposes. Say initially Bank E did not want to lend to Bank N at a rate of +0.1%. The reason was that Bank E judged that +0.1% was not a high enough remuneration given the risk involved and given the remuneration of its reserves (-0.1%): the +0.2% gain associated with a loan to Bank N (0.1-(-0.1)) was not appealing enough given the risk involved. However, bank E was ready to lend to bank N at a rate of +0.2%, since the +0.3% associated gain was judged more appropriate for the risk involved. At this rate, however, bank N preferred to borrow from the ECB, which offered a lower rate (+0.15%)… In the end, no interbank loan took place.

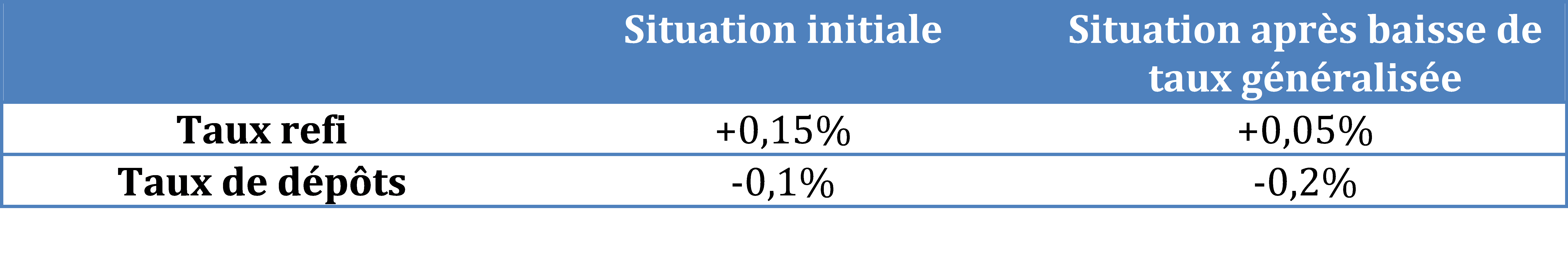

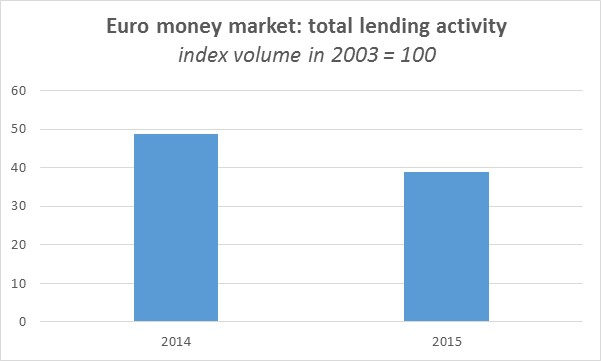

Now, with the decrease in ECB interest rates, the rates at which banks borrow and lend on the interbank market have changed (monetary policy transmission). Bank E, which judged that a +0.3% gain was necessary for it to lend to bank N, is now ready to offer a loan at a +0.1% interest rate to bank N (deposit facility rate of -0.2% now + 0.3% = 0.1%). However, Bank E still refuses to lend if the associated gain is 0.2%, thus if the interest rate on the loan is equal to 0%. As a consequence, the same situation as before will take place: bank N will go to borrow from the ECB at +0.05% now (after the rate decrease) since the rate offered is lower than the one required by bank E. Thus the fact that the interest rate on excess reserve became negative didn’t change anything for the activity of the interbank market: bank R will still not lend to bank N [2]. To put it another way, the negativity of the interest rate on excess reserves has no impact on interbank lending activity. This conclusion is also suggested by the graph below (remember that the ECB went negative in mid-2014 and cut rates further at the end of 2014).

Source: ECB, BSi Economics

2. How a negative interest rate could still be associated with an increasing velocity of reserves: the corridor rate effect

An increasing velocity of reserves on the interbank market could still be observed after the implementation of a negative interest rate in two cases:

– if the deposit facility rate cut is not associated with a cut in the refi rate (what the ECB did last December). In that case, it is the widening of the ECB interest rate corridor that is responsible for the increasing velocity of reserves on the interbank market, and not the negative deposit facility rate. In the framework discussed above, bank E was willing to lend to bank N only when the associated gain was greater than or equal to +0.3%. Suppose only the deposit facility rate decreased from 10 basis points and the refi remained at +0.05%: bank E has the choice between borrowing from bank N at 0% or from the ECB at +0.05%: it will naturally choose the first option. As a result, interbank lending increases.

– If part of excess reserves are taxed more than the rest of them (partial taxation of excess reserves). Examples of such systems are those recently put in place by the SNB or the BoJ. In that case, the effect is similar to the one described above with the enlargement of the corridor: bank E will find an interest in lending to bank N its more heavily taxed excess reserves at a rate below the refi rate, thus interbank lending will increase.

Conclusion

Hence, a negative interest rate on banks’ excess reserves per se cannotbe expected to lead to an increasing velocity of reserves on the interbank market. However, an enlargement of the central bank’s interest rate corridor can produce this outcome. This effect could be obtained irrespective of the deposit facility rate.

Although the ECB decided to widen its interest rate corridor at its last December meeting by lowering only its deposit facility rate (to -0.3%), it is unlikely that this move was aimed at increasing interbank lending activity. After one year of QE, liquidity is no longer a problem for the vast majority of banks in the Eurozone. Moreover, the Fixed-rate allotment procedure (FRFA)[3], which started after the crisis, still allows banks to borrow whatever amount of liquidity they need from the ECB. The intended effects of such a policy measure are more likely to be on the exchange rate.

Julien Pinter

References:

Pinter, J. (2015): The ECB’s negative rate: a few comments to clear up any confusion. BSi Economics

Kaminska, I. (2012): The base money confusion. FT Alphaville

Standard&Poor’s Ratingsdirect (2013): Repeat After Me: Banks Cannot And Do Not « Lend Out » Reserves

Stella, P. (2014): The Negative Rate Chrono Synclastic Infundibula. Stellar Consulting.

Notes:

[1] See Stella (2014) for a full discussion. Pinter (2015) and Ducrozet (2015) eg also provide further details.

[2] Supposing that there is an « incentive effect » implies supposing that banks are willing to take on more risks with the negativity of the interest rate on excess reserves.

[3] See this very educational post.

ENGLISH VERSION

Could the ECB’s negative interest rate encourage banks to lend more to each other?

The ECB’s negative interest rate cannot be intended to encourage banks to lend more to households or businesses via a « punitive effect »: the invalidity of this argument has been discussed many times in our publications (BSi Economics 2015, Le Monde 2015) and by other economists (Ducrozet, 2015; Stella, 2014). The simplest reason for this (among others) is that banks’ liquidity is not transferred to households or businesses when a loan is granted.

But what about interbank lending, where banks’ liquidity is effectively transferred? Could the negative rate create a potential incentive for banks to lend more to their peers? If this channel worked, it would increase the liquidity of the interbank market, which would ultimately be good for the economy. Some observers suggest this argument.

This article explains why this cannot be the case: a negative rate on banks’ excess liquidity has no reason to have any particular incentive effect on interbank lending (part 1). However, we explain that greater liquidity circulation in the interbank market may occur following the introduction of a negative rate in two specific cases (part 2): (1) if only the deposit rate is lowered (widening of the corridor around the key interest rate) (2) if only part of the excess liquidity is taxed (partial taxation of reserves). This is not due to the negative rate: the same mechanism would be at work with a positive rate. Nevertheless, it is highly unlikely that the ECB implemented (1) (widening of the corridor) last December or will implement (2) (partial taxation system) next March with the implicit aim of reviving the interbank market (conclusion).

1. An invalid theoretical argument

Let us analyze the mechanical argument itself. Suppose that all reserves[1]are taxed at -0.1% (initial case), and consider a general reduction in key interest rates of 0.1% so that we move to a negative rate of -0.2% and a refi rate (the rate at which banks can borrow from the ECB) of +0.15% to +0.05% (a move observed in September 2014). Banks with excess reserves are therefore « taxed » more heavily. According to the previous argument, they would therefore want to get rid of more of their reserves when the rate becomes more negative, since the reserves are taxed more heavily. Does this make sense? The answer is no, because we need to look at the opportunity cost and not the « absolute rate. »

Let’s take two representative banks: Bank RE, which has excess reserves, and Bank B, which needsliquidity. If, previously, Bank RE did not want to lend to Bank B, which was offering it a rate of +0.1% to borrow liquidity, it was because it considered that the +0.1% return was not attractive enough given the risk and the current return on its liquidity (-0.1%): the gain of +0.2% (0.1 – (-0.1)) compared to the situation where it would keep its liquidity was not attractive enough given the risk. On the other hand, Bank RE, like all other banks, wanted to lend to B at a rate of +0.2%, as this guaranteed it a gain of +0.3% (0.1 – (-0.1)), which was more appropriate for the risk involved. But at that rate, Bank B preferred to turn to the central bank, which offered it a refinancing rate of +0.15%.[2]each week. In the end, there was no interbank lending.

Now, with the ECB’s deposit rate falling from -0.1% to -0.2%, credit conditions on the interbank market have changed (monetary policy transmission). Bank RE, which considered that a gain of +0.3% was necessary given the risk of lending to B, is now willing to lend at a rate of +0.1% (-0.2% + 0.3%). However, it still refuses to lend if the associated gain is +0.2%, i.e., at a rate of 0% in this case. Ultimately, Bank B will do the same as before, i.e., borrow from the central bank at the refi rate, this time at +0.05%. It is therefore clear that the fact that the rate is more negative does not change anything in terms of activity on the interbank market. Bank RE has no additional incentive to lend to Bank B after the rate has become more negative.[3]. In other words, the negative deposit rate has no effect on interbank activity. This is also suggested by the data on interbank market activity in practice in the graph below (reminder: the ECB introduced the negative rate in June 2014 and lowered it further in September 2014).

Source: ECB, BSi Economics

2. Greater liquidity circulation possible despite the lack of incentive effect: an effect due to the widening of the corridor

It may seem counterintuitive at first glance, but greater liquidity circulation following the introduction of a negative deposit rate is not necessarily due to the negativity of this rate, nor is it the result of an increased incentive to lend. In reality, greater liquidity circulation can occur in two scenarios:

– if the cut in the deposit rate is not accompanied by a cut in the refinancing rate (which is what the ECB did in December). In this scenario, it is the widening of the corridor thatis responsible for this increased circulation of liquidity, not the negative rate itself. To simplify, let’s take the previous scenario where Bank RE only agreed to lend to Bank B at a rate 0.3% higher than the ECB deposit rate. If, when the deposit rate falls to -0.2%, the refi rate does not fall and remains at 0.15%, Bank B can now borrow at +0.1% from Bank RE or at +0.15% from the ECB; it will, of course, choose the first option. As a result, liquidity will therefore circulate more.

– If part of the excess liquidity is taxed more than the majority of it (partial taxation system). A system implemented in Sweden, Switzerland, and Japan, for example. In this case, the effect is similar to that described above with the widening of the corridor: Bank RE will find it advantageous to lend at a rate below the refi rate on its reserves that are taxed more heavily.[4], and the circulation of reserves will increase.

3. Conclusion

Thus, a negative deposit rate does not in itself imply greater circulation of liquidity on the interbank market. On the contrary, it is the widening of the corridor that may be the cause. The same effect could therefore be achieved with a positive deposit rate.

Did the ECB therefore lower the negative rate alone (widening the corridor) last December with the aim of reviving interbank lending? This is unlikely to be the case. Banks are currently flush with liquidity, so they have virtually no problems on that front. In addition, the FRFA (Fixed Rate Full Allotment) procedure[5]) procedure, which has been in place since the beginning of the crisis, has been extended for some time, meaning that banks can obtain all the liquidity they want from the ECB. The effect of the negative rate measure is more likely to be found elsewhere in the case of the ECB, particularly in the exchange rate.

Julien Pinter

References:

Pinter, J. (2015): The ECB’s negative rate: a few comments to clear up any confusion. BSi Economics

Pinter, J. (2014): Negative rates will not encourage lending. Le Monde

Kaminska, I. (2012): The base money confusion. FT Alphaville

Stella, P. (2014): The Negative Rate Chrono Synclastic Infundibula. Stellar Consulting.

Notes:

[1] In this article, « reserves » and « liquidity » refer to the same concept.

[2] The rate consistent with the previous figures would have been +0.05% of course (current refi rate), but this figure is more suitable for the explanation.

[3] Assuming that there is an incentive effect is in fact tantamount to assuming that banks are taking greater risks, as they would now agree to lend at low margins despite the risk. It is the risk-taking channel that is at issue here rather than a specific effect of the negative rate.

[4] It is also possible in this case that the arbitrage mechanism described in footnote 2 is less efficient (insufficient number of market players), which also implies greater liquidity circulation.