Summary:

-The cost of equity capital corresponds to the return required by shareholders on their investment in equity capital. This is higher than that required by creditors because shareholders take a greater financial risk.

-However, the Modigliani-Miller theorem (1958) states that under certain assumptions, the (weighted average) cost of capital for a bank does not depend on the proportion of equity in the financing structure.

-In practice, distortions exist (interest deductibility, deposit guarantees, information asymmetries between management and investors), so that a bank’s financing cost increases with the proportion of equity capital. However, this phenomenon seems to be mitigated by the decline in the cost of equity and debt (Modigliani-Miller effect).

-What can prove costly, especially for a bank, is raising equity capital in a context where stock market investors are overly pessimistic, or when there are significant information asymmetries between them and the managers who run the bank. Future profits are then valued less highly, which reduces the amount of money that can be raised for a given number of shares.

The economic and financial context since 2008 has led to a tightening of prudential requirements concerning banks’ capital. This is a costly but necessary requirement to reduce the risk of a financial crisis.

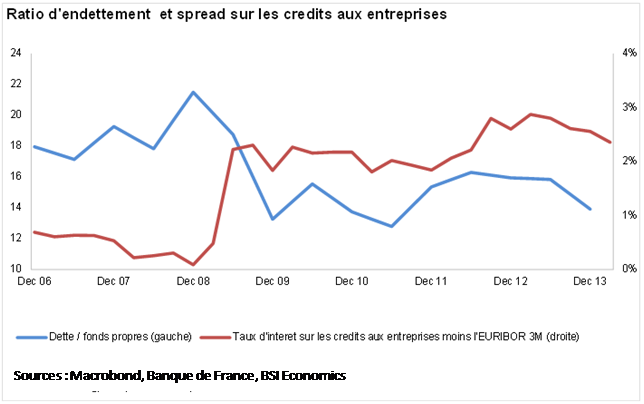

Costly? The deleveraging of French banks listed on the stock market since 2008 has indeed been accompanied by an increase in spreads on corporate loans (Chart 1). However, banks tend to pass on their financing costs to economic agents. Has the increased weight of capital in bank financing therefore led to an increase in their financing costs?

Chart 1

1 – In theory, in the absence of distortions, debt financing is equivalent to equity financing (Modigliani-Miller theorem).

Banks have a wide variety of funding sources: equity capital, deposits, debt securities (asset-backed or unsecured, with varying degrees of priority in the event of financial difficulties, and potentially convertible into shares), and loans from the central bank. But fundamentally, banks finance themselves through debt or equity capital, with deposits being just a particular form of debt. Does the choice of financing structure have an impact on the cost of financing?

The theorem[1]theorems (1958) provide a theoretical answer: in the absence of certain distortions[2], the financing structure is neutral for the value of a company: whether a bank finances itself through debt or equity, this does not change its weighted average cost of capital. This theorem is now considered the fundamental theorem of corporate finance.

The cost of equity corresponds to the return required by shareholders on the equity they have invested. For a publicly traded company, the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) posits that this rate of return is equal to the rate on the safest government bonds plus a risk premium. According to this model, this risk premium depends on the sensitivity of the share price to stock market fluctuations. This sensitivity is described by the share’s « beta. » In practice, the cost of equity defines shareholders’ expectations in terms of return on equity (net income for the year divided by equity at the beginning of the year) and determines how they value future earnings when seeking to value a stock.

This required return on equity is higher than that required on debt because shareholders are in a riskier financial position, being the first to absorb losses. Despite this, the Modigliani-Miller theorem states that more equity in the capital structure does not change the weighted average cost of capital, as the cost of debt and the cost of equity both decrease. The cost of equity capital decreases because less debt in the financing structure means less variability in net income (in finance, debt represents the equivalent of a fixed cost). The cost of debt also decreases because it becomes less risky, with creditors being protected by more equity capital. In other words, the mix effect (more equity) is exactly offset by the price effect (lower cost of debt and lower cost of equity).

2 – In practice, a bank’s financing costs increase with the proportion of equity, but this phenomenon appears to be offset by the decrease inthe cost of each component of capital (Modigliani-Miller effect).

The assumptions of the Modigliani-Miller theorem are not verified in reality. For example, interest on debt is deductible from taxable income, deposits are guaranteed by the government up to a certain amount, and investors are by definition less well informed than the managers who run the bank. The question then is to what extent the result of this theorem still holds (the Modigliani-Miller effect).

Quantifying the Modigliani-Miller effect in the case of banks is an exercise undertaken by a group of economists led by David Miles, who became famous for advocating a capital ratio twice as high as that of Basel III. In order to estimate the effect of bank deleveraging on the cost of their equity capital, these economists estimated the effect of the change in the debt ratio on the beta of the stock market share. The following figures (to the nearest decimal point!) are intended only to illustrate the Modigliani-Miller effect.

The CAPM estimates the cost of equity for French banks at 8.5% at the end of 2006. Given that the debt/equity ratio was then 18 on average, and making a few standard assumptions, we can assume a weighted average cost of capital for French banks of 3.6% at the end of 2006. Their deleveraging resulted in an average debt-to-equity ratio of 14 at the end of 2013. If only the financing structure had changed in seven years, we can estimate, based on the relationships obtained by David Miles, that the cost of equity and the weighted average cost of capital would have been 8% and 3.64% respectively at the end of 2013. In the absence of any Modigliani-Miller effect, we can estimate that the weighted average cost of capital would have been 3.68% at the end of 2013. Thus, the increased share of equity in the financing structure appears to have led to an increase in the weighted average cost of capital (4 basis points) that was 50% lower than it would have been (8 basis points) in the absence of the Modigliani-Miller effect.

3 – What can be costly, above all, is raising equity capital when the market is overly pessimistic or when there are significant information asymmetries.

Chart 2:

Today, French bank shares are trading at a price below their book value (Figure 2). A price-to-book ratio of less than 1 can be interpretedas a sign of market skepticism about a bank’s ability to generate a return on equity (ROE) higher than that expected by stock market investors. The parallel with a bond helps to understand this intuitively: a fixed-rate bond trades below its nominal value (analogy with the price/value ratio) if its internal rate of return (analogy with the cost of equity used to value a share) is higher than its nominal interest rate (analogy with the future profits linked to holding the share).

Given that the cost of equity for banks currently appears to be around 10% and that their price/book ratio is around 0.8, the market seems to be showing some caution about their ability to generate a ROE of more than 10%, which is precisely the medium-term target announced by several banks.[3]. An ROE of 5%[4]on average in 2013 shows that it is possible to be uncertain about this.

In this context, let us assume that a bank wishes to raise equity capital while the market doubts its ability to achieve its return on equity target, either out of pure pessimism or due to a lack of information. The amount that the bank could raise for a given number of shares would be lower than if the market shared the same expectations as the bank. In this sense, raising equity capital can be expensive.

Conclusion

At a conference, Merton Miller once made the following remark to a speaker from the banking sector who was complaining about the constraints of capital requirements on his institution’s ability to grant loans: « Why don’t you raise equity capital? » The speaker replied: « We can’t, with a price-to-book ratio of 0.5, it’s too expensive. » Was there a contradiction? No, the Modigliani-Miller theorem refers tohaving equity, not to raising equity. Miller thus acknowledged that the banker was not necessarily wrong…and that neither was he.[5]!

References:

References:

[1]The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment, Franco Modigliani and Merton H. Miller, The American Economic Review, 1958.

[2] That is, without taxes, without information asymmetries (between the company and investors), in the presence of perfect markets (perfectly competitive and imposing no transaction costs) and without bankruptcy costs.

[3] Société Générale, presentation to investors dated May 13, 2014; BNP Paribas, presentation to investors of 2013 annual results.