Banking union: a fundamental but unfinished project (1/2)

Summary:

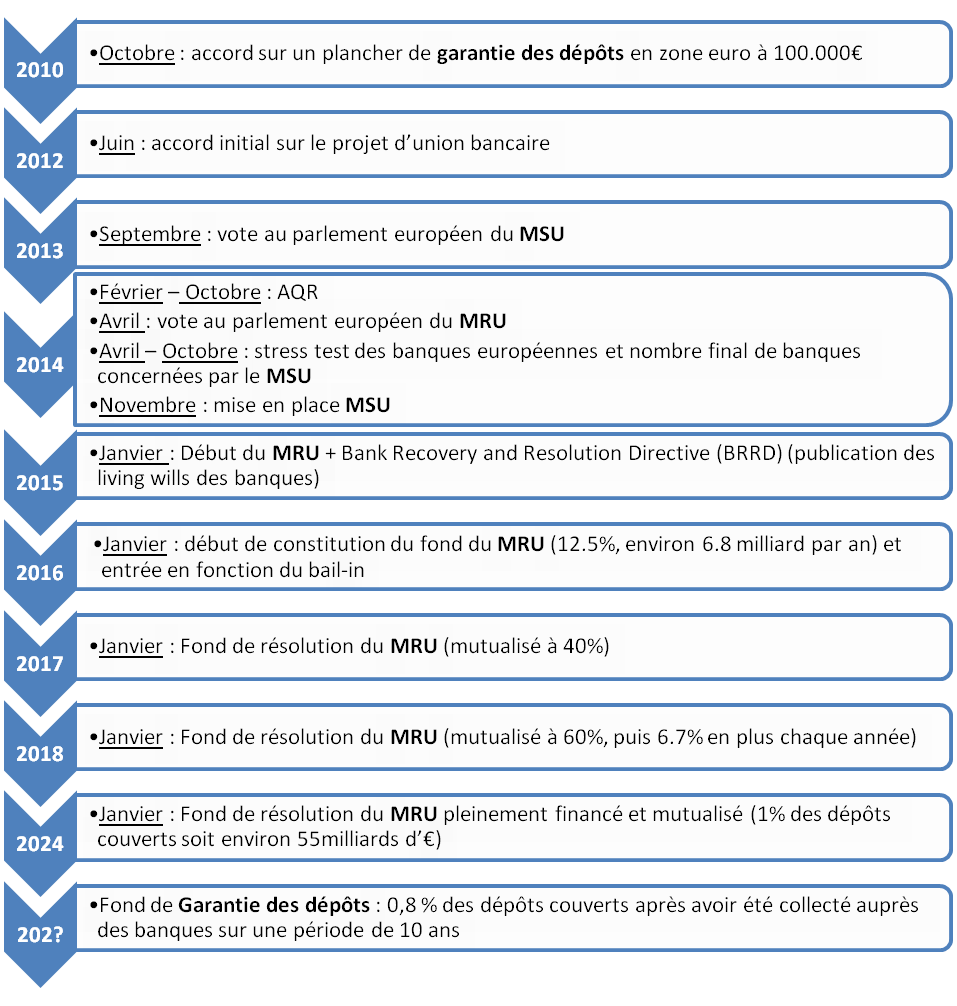

– Banking Union consists of three pillars: the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM), and the deposit guarantee fund.

– The SSM will come into effect in November 2014 and will directly supervise 130 banks.

– The SRM’s resolution rules will come into force in 2015, while the resolution fund will be built up gradually over eight years.

– No agreement has yet been reached on the deposit guarantee fund.

With the vote in the European Parliament on April 15 and the launch of stress tests on European banks on April 30, the final implementation of a project launched in 2012 has never been so close. But what exactly are we talking about when we refer to the Banking Union, why is it presented as a crucial project for Europe, and what challenges remain?

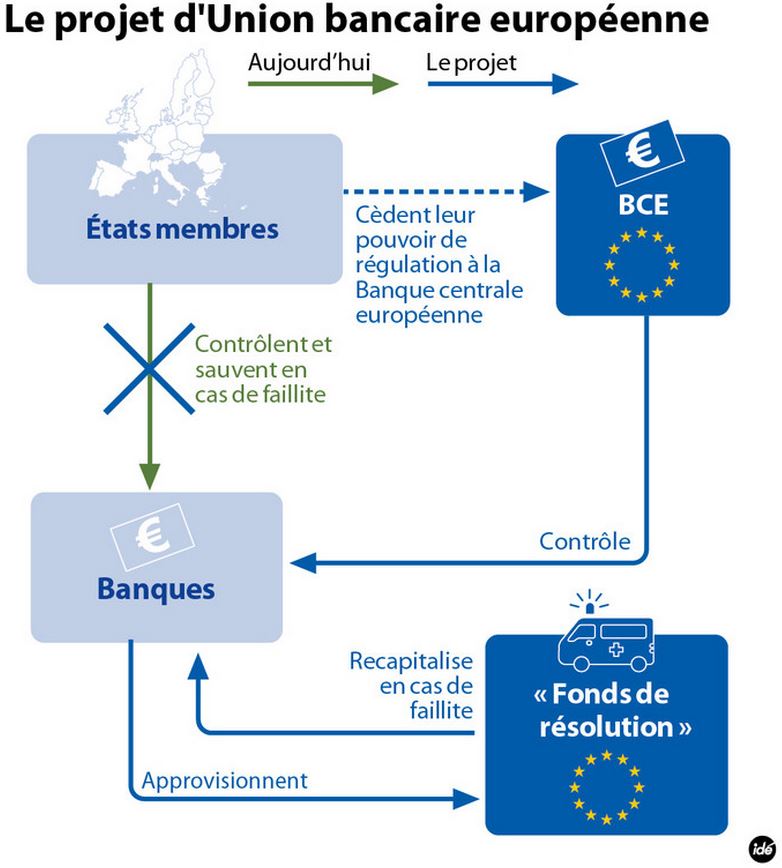

In concrete terms, the Banking Union is above all a major step forward towards greater European federalism. What was once the prerogative of each state, supplemented by minimum European requirements and a slight degree of cooperation[1], is being delegated to the European level. The Banking Union concentrates the powers of supervision and financial crisis management in the hands of European agencies, much like the creation of the euro centralized monetary policy.

What is the structure of the Banking Union?

The Banking Union consists of three interconnected pillars: ① the Single Supervision Mechanism [2], ② the Single Resolution Mechanism [3], and ③ the European deposit guarantee fund.

1 – The Single Supervisory Mechanism

Voted in September 2013, the SSM came into effect onJanuary 1, 2014. The European Central Bank (ECB) became the single supervisor of banks, responsible, for example, for monitoring the implementation of Basel III and banks’ risk models. The banks concerned are those in the eurozone and in European Union countries wishing to participate in the SSM.

However, not all 6,000 banks in the eurozone are under the direct supervision of the ECB. Only those with assets exceeding €30 billion, or whose weight exceeds 20% of GDP, or which have received support from the EFSF or the ESM are concerned. However, the three largest banks in each country are automatically placed under the supervision of the ECB. Based on these criteria, approximately 130 banks, representing 80% of the eurozone’s assets, are placed under the responsibility of the ECB. However, the final number will not be disclosed until November 2014, once the results of the AQR[4] and stress test[5] of eurozone banks have been disclosed. The other banks will remain under the responsibility of national supervisors, but the ECB also has the right to intervene in any bank in a country participating in the SSM if it deems it necessary.

Danièle Nouy (former Secretary General of thePrudential Control and Resolution Authority, the authority responsible for banking supervision in France), who took over as chair of the SSM’s management committee in January 2014 for a five-year term. She will be supported by Sabine Lautenschläger, member of the ECB’s Executive Board, as vice-chair. Both were appointed by the Council of the European Union and approved by the European Parliament. In addition, three representatives of the ECB (Sirkka Hämäläinen, Julie Dickson, Ignazio Angeloni) and one representative from each national supervisory institution of the countries participating in the SSM complete the SSM’s management board.

The SSM will have the power to impose capital buffer requirements and apply more restrictive measures to combat systemic risk. Finally, in the event of a breach of capital requirements, the ECB and national regulators will have the power to impose administrative sanctions on banks, such as fines or penalties.

2 – The Single Resolution Mechanism

Voted on April 15, 2014, the SRM is to be phased in gradually from January 2015. Unlike the SSM, the SRM is not directly integrated into the ECB and remains a relatively independent institution, but is, by virtue of its function, closely linked to the ECB and accountable to the European Parliament. The geographical scope of the SRM is the same as that of the SSM.

As the creation of the SRM was only recently voted on, no members of the future management committee are known at this time, but the structure is expected to be fairly similar to that of the SRM. The chair, vice-chair, and four permanent members will be appointed by the Council of the European Union and approved by the European Parliament. In addition, there will be representatives of the national authorities involved in the resolution process (executive sessions) or of all national authorities participating in the SRM (plenary sessions), as well as representatives of the ECB as observers.

The main new feature is the introduction of a » bail-in » when a bank encounters difficulties. Banks will first have to use their own capital (the numerator of the Basel III solvency ratio) to cover their losses, then they will call on their investors and finally their creditors (the bank’s debt holders), which include depositors (within the limits of the deposit guarantee described below). Under this « bail-in » framework, banks will have to provide resolution plans or « living wills » by January 2015. The SRM is responsible for implementing these plans for the resolution or liquidation of a bank.

The MRU also has a fund that can be called upon once at least 8% of the bank’s liabilities have been used up in the restructuring and in order to allow minimum functioning for the bank’s customers during the restructuring or bankruptcy of the bank. This fund, which has been the subject of much debate, as we will discuss below, will be built up gradually over eight years (12.5% per year). It is calculated on the basis of deposits covered by the deposit guarantee and will ultimately represent 1% of these deposits. From 2015 onwards, each national regulator will be responsible for collecting contributions from banks under its jurisdiction each year during the transition phase. These contributions, collected at national level, will be gradually pooled at European level (40% of the funds collected in the first year, then 60% in the second and finally 6.7% each year). Ultimately, in January 2024, this fund will represent €55 billion but will also have the possibility of borrowing on the markets if necessary, and even turning to the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). However, no state will be able to contribute to this fund, or only on a transitional basis during the ramp-up phase.

In the context of a bank resolution, the MRU may be called upon by the ECB (MSU) or may take action itself if it deems it necessary. Three conditions must be met for a bank to be taken over by the MRU: (1) the bank is bankrupt or close to bankruptcy, (2) there are no alternatives involving the private sector, (3) resolution action is necessary in the public interest. Once the ECB (MSU) and the MRU Governing Board have established that these three conditions are met, a resolution plan is put in place by the MRU, with the European Commission and the Council of the European Union having the right of veto.[6] over the resolution plans proposed by the SRB. The procedure provides for default approval (« silent procedure ») if the Commission does not respond. If the rejection is based on the fact that point (3) is not met, the bank is then subject to the law of its country of residence. The aim is for a resolution plan to be put in place in less than 32 hours (the time between the close of markets in the United States on Friday and their reopening in Asia on Monday). The MRU’s board of directors can take decisions in executive session if the bailout amount is less than €5 billion. Above that amount, the plenary session can take over the case if it deems it necessary. Decisions at the plenary session will be taken by double qualified majority: if only the pre-existing fund is used, a simple majority and 30% of the fund’s contributions will be required; if borrowing or committing funds not yet constituted is necessary, a two-thirds majority and 30% of the contributions will be required (50% during the transition phase).

3 – The European Deposit Guarantee Fund

Apart from the 2010 decision to harmonize deposit guarantees within the eurozone at €100,000, no structure has yet been put in place. The management and provisioning of this fund remains the responsibility of each Member State for the time being. Under the third pillar of the Banking Union, there are plans to pool the funds collected from banks in the euro area with the aim of setting up a provisioned fund covering 0.8% of covered deposits over a period of 10 years from the date of the vote on this project. Negotiations are currently underway. This fund will therefore most likely not be established before 2025 at the earliest.

- Summary of the Banking Union and its implementation schedule

Conclusion

The Banking Union consists of three pillars, which are interdependent and will be implemented gradually between 2014 and 2024. The final structure of the guarantee fund remains undecided, as no final agreement has yet been reached on this issue.

Notes:

[1] Supervisory colleges have been set up since 2010 to strengthen cooperation between entities responsible for supervising the financial system, such as the European Systemic Risk Board.

[2] See the article on BSI Economics by Victor Lequillerier: « And then came the Single Supervisory Mechanism… »

[3] See Morgane Delle Donne’s article on BSI Economics: « Banking union: will the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) replace Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) in the management of banking liquidity crises? »

[4] The Asset Quality Review conducted from February to October 2014 by the EBA (European Banking Authority) aims to scrutinize balance sheets, off-balance sheet commitments, asset weightings in the solvency ratio, financing structures, and their vulnerability to liquidity shocks.

[5] The stress test scenarios were disclosed on April 30, 2014, and include a baseline scenario for economic developments between 2014 and 2016, as well as a much more severe adverse scenario. Banks have until October to submit information on the impact of these scenarios on their balance sheets.

[6] The role of validating resolution plans, which has been assigned to the Commission, is due to the fact that decisions at the European level must be taken by European bodies so as not to require an amendment to the European Constitution.

References:

– Agarwal, Sumit, David Lucca, Amit Seru, and Francesco Trebbi, (2012), « Inconsistent Regulators:

Evidence from Banking, » National Bureau of Economic Research, No. 17736, January.

– ECB, (2014), « Progress in the operational implementation of the Single Supervisory Mechanism Regulation, » SSM Quarterly Report 2014/2

– Jézabel Couppey-Soubeyran, (2013), Interview, « The Banking Union, an incomplete project , » BSI Economics

– Christian de Boissieu, (2014), “Towards a Banking Union: Open Issues”, report of Conference co-organized by the College of Europe and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre in Bruges in April 2013

– Duncan Lindo, Katarzyna Hanula-Bobbitt, (2013), “Europe’s banking trilemma”, Finance Watch

– Jeffery Gordon, Georg Ringe, (2014), « How to save bank resolution in the European banking union, » Vox

– MEMO/13/1176, European Commission (2013)

– MEMO/14/295, European Commission (2014)

– Morgane Delle Donne, (2013), “ Banking union: will the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) replace Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) in the management of banking liquidity crises? , » BSI Economics

– Patrick Artus, Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, Laurence Boone, Jacques Cailloux, and Guntram Wolff, (2013), » A Three-Step Path to Reunify the Euro Area, » CAE Working Paper

– Rishi Goyal, Petya Koeva Brooks, Mahmood Pradhan, et al., (2013), « A Banking Union for the Euro Area, » IMF Staff Discussion Note February 2013 SDN/13/01

– Thorsten Beck, (2013), « Banking union for Europe – where do we stand? », Vox

– Victor Lequillerier, (2013) , » And then the Single Supervisory Mechanism arrived… , » BSI Economics

– Zsolt Darvas and Silvia Merler, (2013), “The European Central Bank In The Age Of Banking Union”, Bruegel Policy Contribution Issue 2013/13 October 2013