Abstract:

- While economic activity is expected to rebound in China in 2023 (nearly +4.8% after an estimated +3.2% in 2022 according to the December 2022 Bloomberg Consensus), several downside risks surround GDP growth forecasts. The Chinese economy is expected to face four major challenges in 2023.

- Despite the announcement that the « zero Covid » strategy is being abandoned, the new wave of infections poses a real threat and is likely to delay the recovery in private consumption.

- The real estate crisis, which erupted at the end of 2021, intensified in 2022. By weakening several major economic players (real estate developers, but also banks and local governments), this real estate crisis is likely to continue to weigh on activity in 2023.

- After significant public support in 2022, further measures are expected in the first half of 2023. However, the fiscal and monetary authorities’ room for maneuver does not appear to be as wide as it seems.

- While local uncertainties raise questions about China’s growth figures, the international context is hardly more favorable and could result in a sharp slowdown in external demand.

In China, economic activity was rather disappointing in 2022. In a rather unusual move, the GDP growth target of +5.5% announced by the authorities in March 2022 was ultimately not achieved; growth was close to +3% for 2022, according to the main forecasting institutes, and the World Bank even predicted +2.7%[1]. Health management and the relentless pace of lockdowns weighed heavily on activity, particularly on domestic demand.

In November and December 2022, the authorities finally opted to shift their « zero Covid » strategy, which in principle should promote an economic recovery in 2023. A rebound in activity in the world’s second-largest economy is therefore anticipated for 2023 (real GDP growth of between +4.3% and +5.2% according to forecasters), but many doubts remain. The Chinese economy is likely to face several challenges, and downside risks weigh on the short-term outlook: (i) the health threat, (ii) a deep real estate crisis, (iii) the limits of proven economic policies, and (iv) a delicate international context.

This article focuses on the latter two challenges, with the former challenges discussed in another note.

Challenge 3: Economic policy margins have been tested

What is the situation?

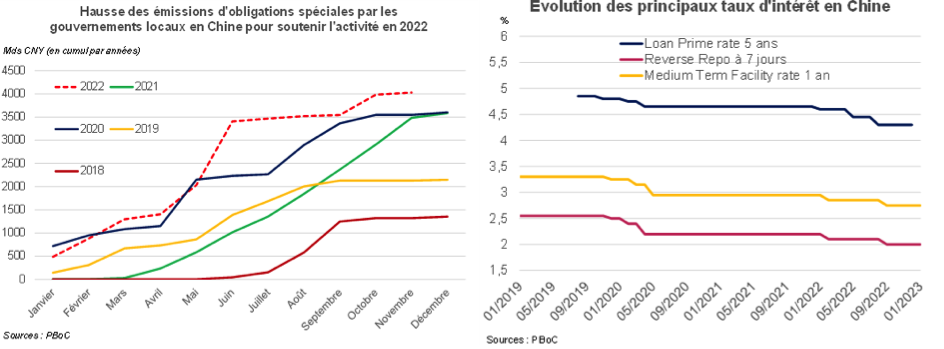

Since 2020, fiscal and monetary policies have been heavily used[2] to support economic activity in China. Against an unfavorable health backdrop in 2022, public spending rose by +6.2% in the first eleven months of the year compared with the previous year, while tax revenues fell by -7.1%. In addition, in order to finance infrastructure investment projects, local governments were authorized to issue a large amount of bonds (see chart below left) and to exceed their quotas for 2022 by using part of the issues initially planned for 2023. As a result, the public deficit widened significantly (-8.9% of GDP in 2022 according to the IMF, compared with -3.9% of GDP on average between 2015 and 2019). While the low level of central government debt (20.2% of GDP in H1 2022) suggests ample fiscal room for maneuver, the deteriorating public finances of local governments call for greater caution.

Taking advantage of relatively low inflation[3], the central bank (PBoC) eased financing conditions in 2022 (see chart above right) and increased its monetary support[4], leading to an 11% increase in yuan-denominated credit in 2022. However, monetary margins remain limited, with the PBoC facing two major obstacles: i) monetary support must be balanced with financial stability imperatives, while domestic debt levels are close to 245% of GDP (excluding government) ii) downward pressure on the renminbi, which lost an average of 8.3% of its value against the USD in 2022 due to weaker growth prospects and, above all, the desynchronization of its monetary policy with the rest of the world, particularly the United States.

Why is this important?

At the end of 2022, the authorities announced targeted fiscal support in 2023 for: real estate (see Challenge 2), domestic demand, SMEs, and tech industries. In principle, the initial benefits of infrastructure investments since 2021 should be felt in 2023 before gradually slowing down.

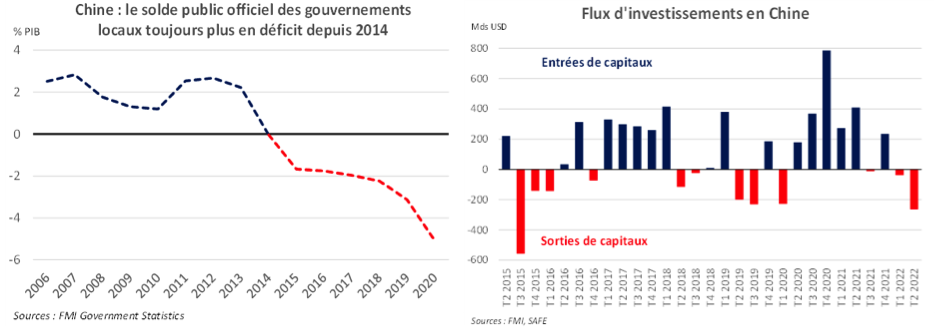

In China, most of the fiscal support is provided by local governments, which are given annual growth targets to meet. Their public finances, already fragile before the Covid-19 crisis (see chart below left), have been further weakened by: i) fiscal stimulus since 2020, ii) the slowdown in activity and the real estate crisis in 2022. According to official figures, local government debt is expected to reach 29% of GDP in 2022 (22% in 2019). However, these figures do not take into account all the opaque financing vehicles that local governments have been using for more than a decade to meet their significant financing needs. According to the IMF, these vehicles could represent up to 44% of GDP in 2022, bringing total local government debt to 73% of GDP, which is a significant level.

While some local governments with a significant share of GDP (Guangdong, Jiangsu, Henan, Fujian) have sufficient budgetary margins, others (Qinghai, Guizhou, Inner Mongolia, Tianjin) would find it difficult to service their debt. In addition, some local governments will see their margins reduced as they may be called upon in 2023 to support developers or public banks embroiled in the real estate crisis (see Challenge 2). This situation would prove problematic and would undermine the financing of infrastructure projects in the short term, as well as more ambitious projects to expand private consumption in the medium to long term (see Evelyne Banh’s note on BSI Economics about the « Common Prosperity » strategy).

Since the late 2010s, financial stability has been made a priority, and several measures have been taken to this end. However, with the Covid-19 crisis, the need for intervention has led to an acceleration in bank lending, even if it means temporarily putting financial stability objectives on hold. Given the already very high level of corporate debt in China, stimulus via bank lending can only be used sparingly, at the risk of increasing the chances of financial instability. The repercussions would be all the more damaging to the quality of banks’ loan portfolios, at a time when most rural banks are already facing a rapid rise in non-performing loans and smaller banks are recording solvency ratios below the levels required by the regulator[8].

Furthermore, the desynchronization of the PBoC’s monetary policy with that of other major central banks is leading to greater volatility in the renminbi. As a result, the PBoC and state-owned banks are likely to continue intervening in the foreign exchange market in 2023 to ensure greater stability of the local currency. At a time when the Chinese economy is gradually opening up its financial account to foreign investors, reducing the volatility of the renminbi is essential to ensure the attractiveness of the Chinese financial market and also to avoid capital outflows (see chart above right).

What indicators should be monitored?

- The announcements and amounts of fiscal stimulus during the two sessions (Lianghui) in March 2023, which will set out the broad economic guidelines and growth targets for 2023.

- Whether or not bond issuance quotas for local governments will be revised for 2023-2024.

- Announcements concerning the introduction of new taxes at the local level, particularly a harmonized property tax to usher in a new era of revenue accumulation for local governments.

- The initial results of the rollout of the « Common Prosperity » strategy in Zhejiang (job creation, per capita income, inequality, etc.) to provide an initial overview of the effectiveness of the measures implemented in this test region.

- All of the PBoC’s monetary decisions to assess the degree of monetary policy accommodation (changes in the reserve requirement ratio, net amounts injected into the MLF market, 5-year LPR rates, and reverse repo rates).

- Monthly changes in the TSF social financing indicator, and more specifically its sub-component related to yuan loans, to estimate the intensity of support through the credit channel.

- The volume and direction of weekly interventions by the PBoC and state-owned banks in the foreign exchange market to support the renminbi exchange rate.

4th Challenge: A delicate international context

What is the situation?

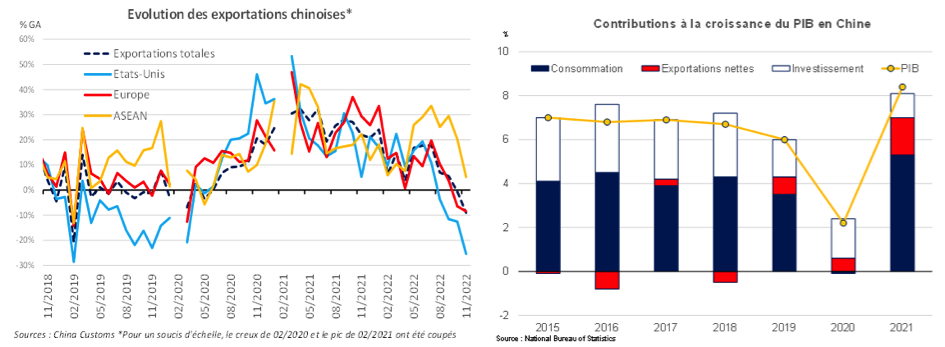

At the end of 2022, Chinese exports entered negative territory. This is a first since the start of the Covid-19 crisis and clearly reflects the first signs of a slowdown in the global economy. While trade with Asian countries remains buoyant, exports to the United States and Europe have declined (see chart below left).

The context of high prices, rapidly rising interest rates and even an energy crisis poses a serious threat to global growth, particularly for developed economies. In November 2022, the OECD predicted a slowdown in global growth from +3.1% in 2022 to +2.2% in 2023. Furthermore, month after month, the likelihood of economic recession in the United States and the European Union is growing. Together, these two regions account for nearly one-third of Chinese exports.

Why is this important?

Net exports make a significant contribution to Chinese GDP growth (see chart above right). The rapid rebound in Chinese exports in the second half of 2020 and their strong performance between 2021 and the first half of 2022 have contributed significantly to the recovery in activity in China. Beyond the impact of the health situation (see Challenge 1) on trade dynamics in 2023, a prolonged slowdown or even a decline in trade linked to a difficult international economic environment would therefore deprive China of an important source of growth.

However, the impact of a decline in external demand on China’s external balances would appear to be more tenuous. In such a context, the current account balance would certainly decline[9] but would remain in surplus (+1.8% of GDP in 2023 according to Fitch, after +2.1% in 2022). Furthermore, it would appear that demand for Chinese goods in certain sectors (electric cars, green equipment, pharmaceuticals) would remain strong and partially offset the slowdown in demand for other categories of goods.

There are many sources of tension with the United States, which have been growing since 2022. These are political (the situation in Hong Kong, the Taiwan Strait crisis), military (maritime influence in the Pacific, purchase of American equipment and electronic components by companies linked to the Chinese military), commercial (failure to comply with commitments to increase Chinese imports from the United States after the trade war with the Trump administration, maintenance of tariffs on Chinese imports) and health (origin of the pandemic, overly rapid relaxation of health restrictions). As China’s largest export partner (18% of exports), any slowdown in trade with the United States is necessarily a source of fragility for China in the short and medium term.

The issue of microchip supplies and the risk of sanctions under the US Chips Actcould also quickly become problematic for China, which is seeking to accelerate the development of its high-tech industry.

What indicators should be monitored?

- Monthly balance of payments data in China and data on new export orders to regularly monitor data and expectations regarding exports.

- Announcements during the two sessions (Lianghui) in March 2023 on specific support measures for exporting companies and the main guidelines on the so-called « dual circulation » strategy.

- Statements by US and even European diplomats regarding China, to « gauge the temperature of relations » and possible protectionist measures on both sides, or even the risk of sanctions.

- The signing of new currency swap agreements between the PBoC and central banks to see if new countries are interested in holding foreign exchange reserves in Renminbi, with a view to strengthening trade ties with China.

Note completed on January 10, 2023.

[1]Forecast dated December 20, 2022. A figure of +2.8% would imply either a slight decline in activity in the last quarter (quarter-on-quarter) or at least a downward revision of the estimated figures for the third quarter.

[2]In 2020, fiscal stimulus accounted for 6.1% of GDP (mainly through increased health spending and deferred charges for businesses) and monetary support was around 3.2% of GDP.

[3]In November, consumer price index growth was +1.6% and producer price index growth was -1.3% year-on-year.

[4]Reduction in reserve requirement ratios between 25 and 50 basis points and net injections of liquidity via the Medium-Term Lending Facility market, etc.

[5]Faced with high inflation, the United States raised Fed Funds rates by 425 basis points in 2022. This rate hike contributed to the appreciation of the USD against other currencies. In the case of China, the widening interest rate differential may also have been responsible for some capital outflows from China, thereby weighing on the value of the renminbi.

[6]On average, 85% of total public spending in China is borne by local governments, even though they generate only 55% of total public revenue.

[7]Strengthening of micro- and macro-prudential measures, in particular to regulate the conditions for access to mortgage credit, strengthening of the supervision and regulation of insurers and management companies, combating the phenomenon of shadow banking, etc.

[8]The ratio of capital to risk-weighted assets for the smallest banks and rural banks averages 12.5%, compared with the 16% required by the regulator.

[9]The trade surplus would narrow due to a slowdown in exports and a possible rebound in imports in the second half of the year if the withdrawal of health measures combined with public support were to boost domestic demand. In addition, the reopening of borders is likely to lead to an increase in Chinese tourism around the world, resulting in a widening of the services deficit.