Purpose of the article: The aim of this note is to understand how emerging countries could be affected by rising interest rates in the United States in 2022 and which countries appear to be the most vulnerable.

Summary :

- In 2022, rising interest rates in the United States would have repercussions for emerging economies (capital outflows, exchange rate depreciation, etc.). However, some countries appear to be more exposed than others.

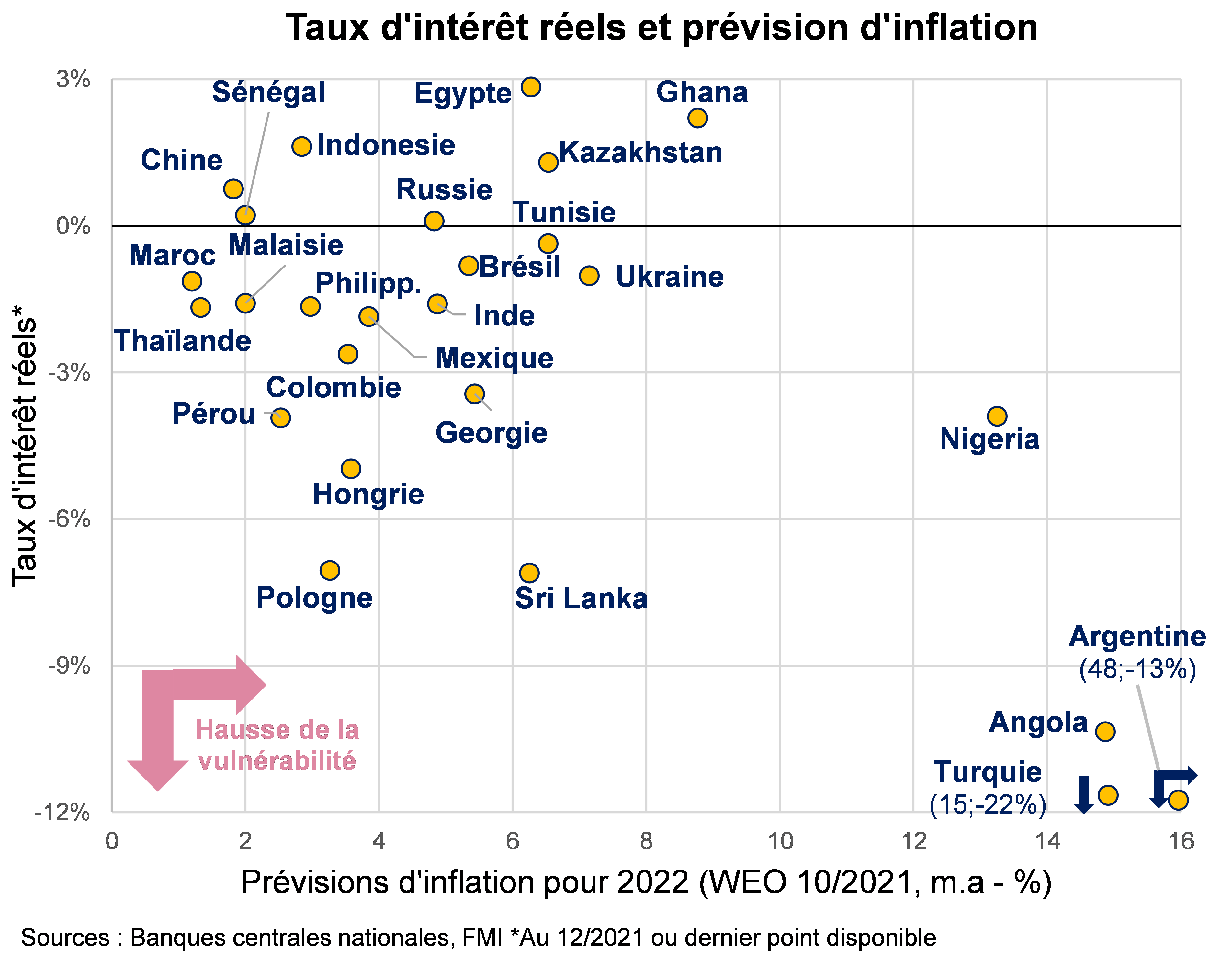

- Countries that are unable to contain inflationary pressures and have negative real interest rates could be relatively more affected (Turkey, Argentina, Nigeria).

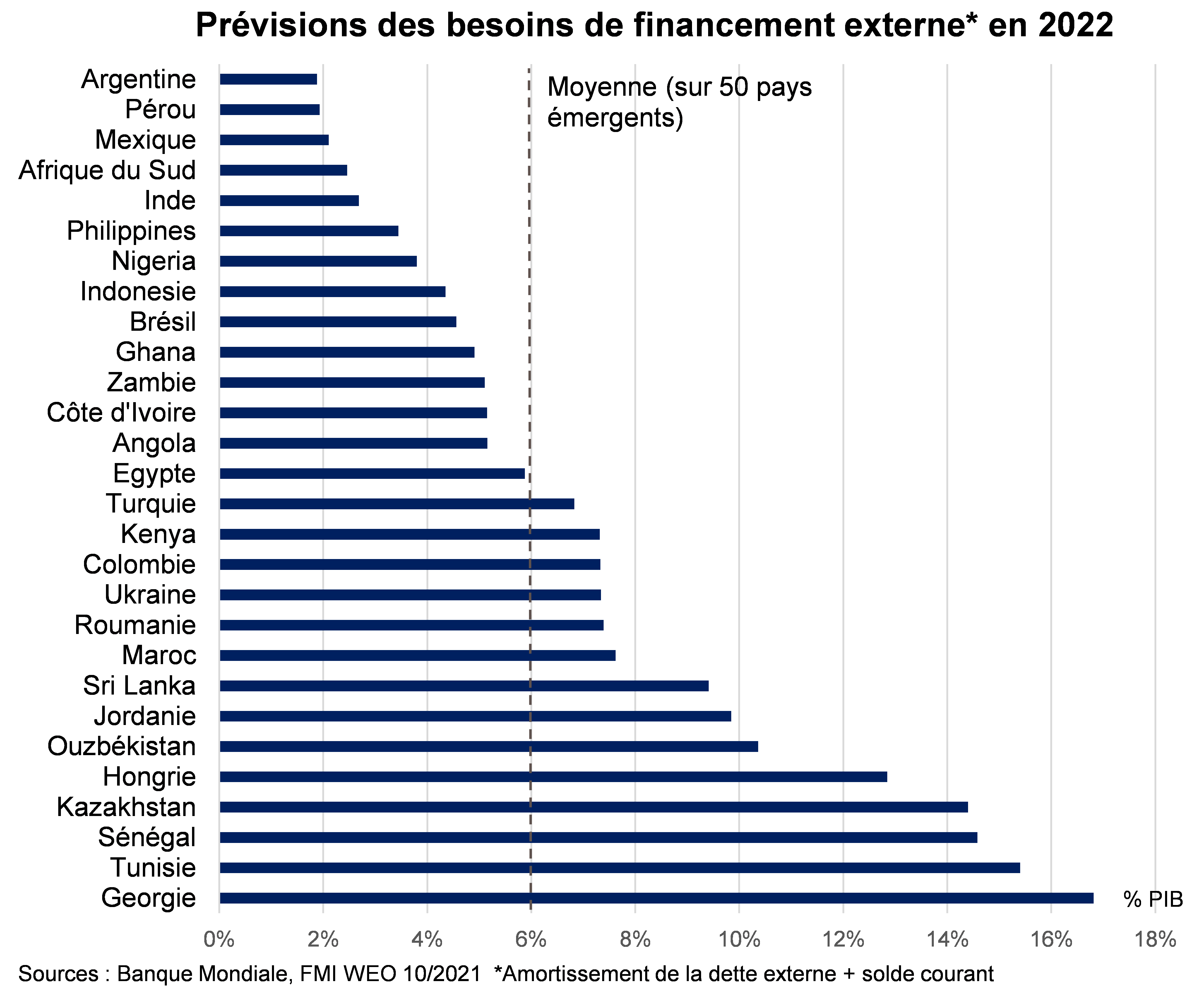

- Countries with high external financing needs in 2022 would be more sensitive to tighter financing conditions (Georgia, Tunisia, Senegal, Kazakhstan).

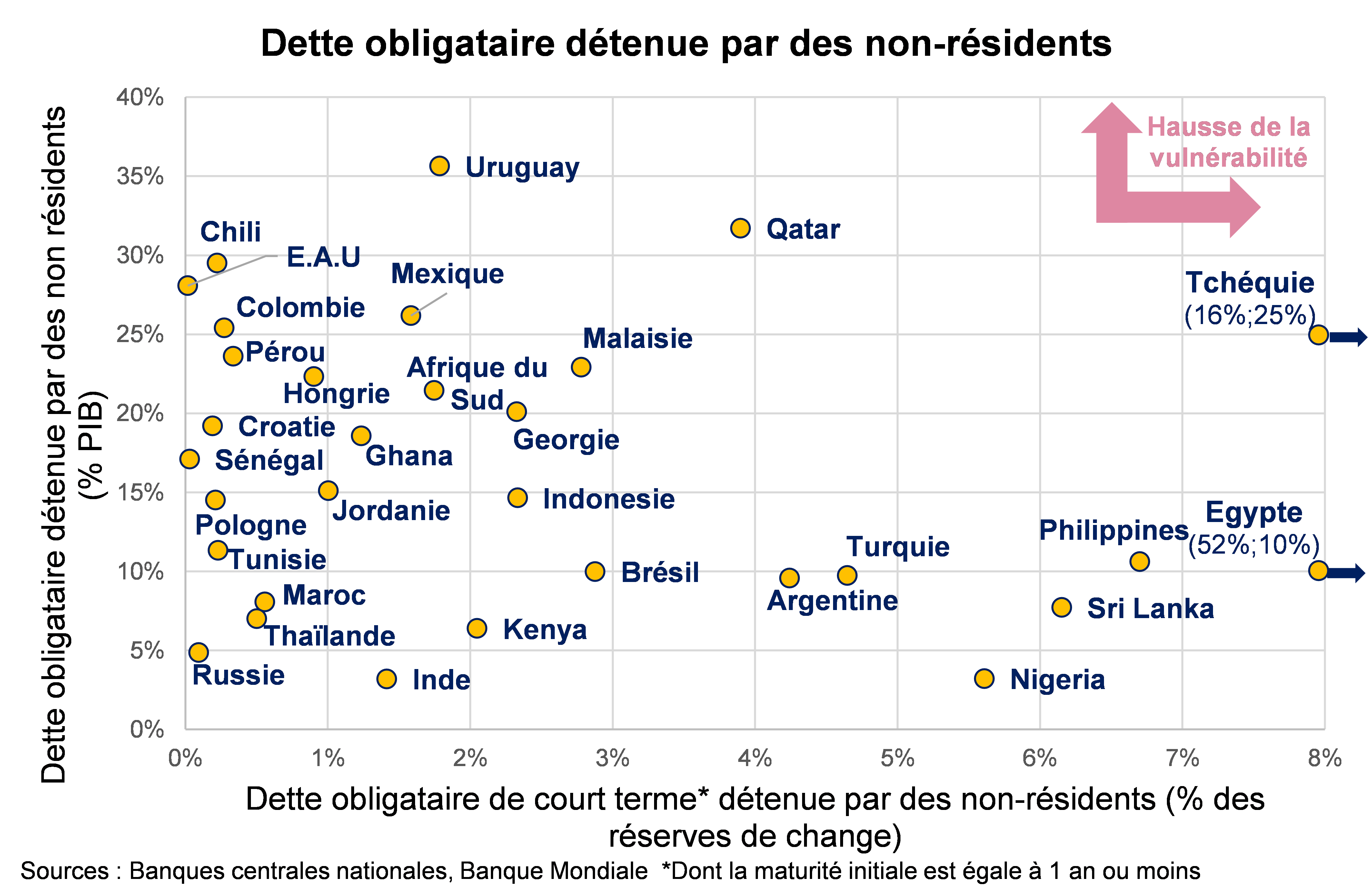

- Countries that are heavily dependent on volatile investment flows (Latin America, South Africa) and where these flows are an important source of foreign exchange reserves would be particularly vulnerable (Egypt, Czech Republic).

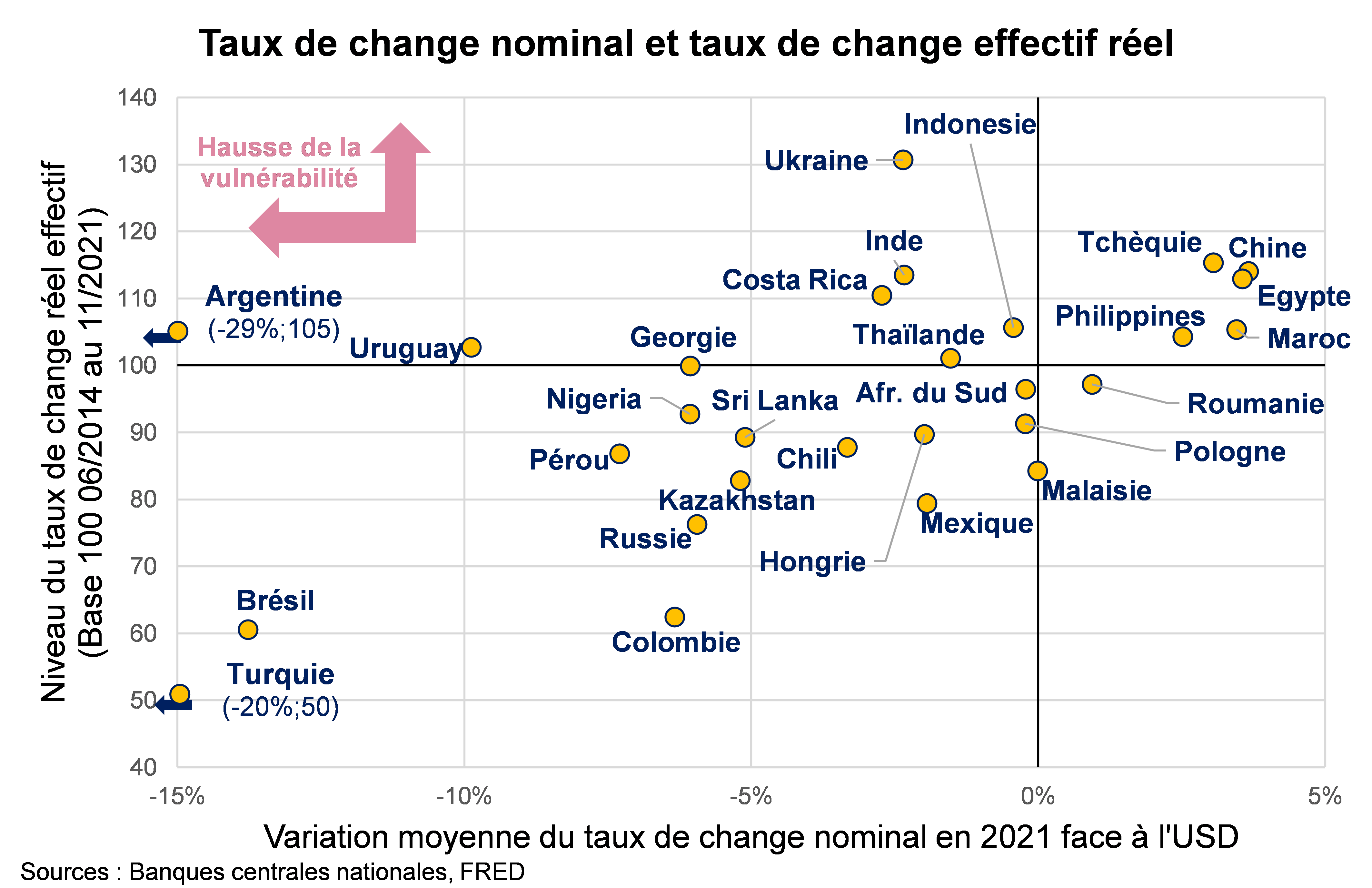

- Emerging market currencies could once again come under downward pressure against the USD in 2022, especially in the most fragile countries (Turkey, Argentina). In addition, countries with overvalued exchange rates (Egypt, China, India) could also see their currencies depreciate in 2022.

In 2022, the US economy will begin a cycle of monetary tightening through: the reduction of asset purchases by the Federal Reserve (Fed) and then probably their cessation from March 2022 onwards, on the one hand, and the Fed raising interest rates (up to four fed funds rate hikes during the year, according to the consensus[2]), on the other.

In the past, these monetary decisions in the United States have caused tensions in emerging countries, particularly in 2013, when massive capital outflows and significant currency depreciation were recorded. When the Fed drastically reduces its asset purchases or raises the fed funds rate, the yield on US securities tends to increase. Investors, attracted by the more favorable risk/return profile of US securities, then shift their investments toward this type of asset, often at the expense of riskier investments in emerging economies, causing capital flows to be redirected from these countries to the United States.

While, in principle, these capital outflows affect all emerging countries, not all are exposed in the same way and are more or less vulnerable depending on the circumstances. The aim of this note is to distinguish the level of vulnerability of these countries in 2022 according to several criteria (real interest rates, inflation forecasts, anticipated external financing needs, dependence on volatile capital flows, exchange rates) with the help of four graphs.

Preserving real interest rates and containing inflationary pressures

The vast majority of countries have been facing rapid inflation since 2021, contributing to a reduction inreal interest rates in several countries, even when national central banks raised their interest rates in the second half of 2021 (mainly in Latin America and Eastern Europe). However, real rates play a key role in the attractiveness of economies to international investors, who are potentially more attracted to high rates and yields (without having to bear significant inflation risk hedging costs).

Maintaining real rates in positive territory in 2022 could therefore protect certain countries from capital outflows compared to other countries with negative real rates. Indeed, in the event of arbitrage between several emerging economies, those with negative real interest rates would offer less favorable opportunities and could be exposed to relatively larger capital outflows.

The chart above shows that at the end of 2021, several countries offered positive and potentially more attractive real interest rates (those at the top of the chart: Egypt, Indonesia, China) than other countries (those at the bottom of the chart: Poland, Hungary, Peru, Georgia).

Some countries will find it even more difficult to achieve a positive real rate if they face high inflationary pressures in 2022. This is mainly the case for countries on the right of the chart above: Ghana’s positive real rate, for example, would be under threat, while Turkey,Argentina, and Nigeria could see their negative real rates deteriorate further. While several central banks are likely to raise their benchmark rates in 2022 to combat rising prices (and thus preserve real rates), they cannot raise them too quickly or too « abruptly » at the risk of causing an excessive tightening of financing conditions, which would weigh on the prospects for recovery (even though most emerging countries have not returned to their pre-COVID-19 GDP levels) or on their public finances.

Finding funds to meet external financing needs

Most countries face external financing needs that vary in size from year to year. A current account deficit requires external sources of financing (such as foreign direct investment or portfolio investment) to cover the needs generated by this deficit, otherwise there is a risk of rapidly depleting foreign exchange reserves, which have already been under pressure over the past two years.

In addition, private companies and public entities sometimes resort to external debt to finance themselves (mostly denominated in foreign currencies). By raising funds in the form of debt, they commit to repaying their creditors, with interest and principal payments according to a predetermined schedule. The amortization of this debt may also require external financing so that these entities can honor their debt within the specified time frame.

The chart ranks countries according to their external financing needs in 2022[7]. On average, financing needs are expected to be around 6% of GDP in the main emerging countries. The intuition here is that the rise in fed funds will cause a tightening of financing conditions globally and a drying up of USD liquidity, the cost of which will automatically increase. Several countries (Georgia, Tunisia, Senegal, and Kazakhstan, for example, with levels above 14% of GDP) could therefore encounter significant difficulties in meeting their financing needs, and/or would do so on much less favorable terms. Conversely, Peru,South Africa, and the Philippines, for example, with ratios below 4% of GDP, should have lower external financing needs in 2022.

Dependence on volatile investment flows: a risky strategy

Borrowing on international capital markets is a double-edged sword. Certainly, countries that are able to make extensive use of international bond issuance are generally perceived as attractive (high yields, positive growth prospects) and enjoy good financial integration and a more or less good reputation as debtors. However, given the highly volatile nature of bond debt, countries are exposed to episodes of capital outflows in the event of financial stress and to a high refinancing risk when the average maturity of their external debt is short.

The chart above shows which economies are heavily indebted to non-resident investors in the form of bond debt. These economies are potentially more exposed to a reversal of the situation, where non-residents would sell their emerging market debt securities, either out of mistrust or through arbitrage in favor of other investment opportunities (such as a more favorable risk/return ratio in the United States following monetary tightening). Countries at the top of the chart are particularly exposed to this type of risk (Colombia, Mexico, Malaysia, and South Africa, for example), where the share of bond debt held by non-residents exceeds 20% of GDP, unlike countries at the bottom left (Russia, India, Thailand, and Morocco), where this share is low.

There is also a risk concerning the impact on foreign exchange reserves. This type of investment flow in the form of bond debt feeds into countries’ foreign exchange reserves, which play a key role[10]. The higher the share of bond debt held by non-residents in the short term, the more countries are, in principle, dependent on volatile short-term financing to fuel their foreign exchange reserves. Consequently, the greater the threat to foreign exchange reserves, especially in a context of liquidity drying up or massive capital outflows. This is particularly the case for countries at the far right of the graph (Czech Republic, Egypt).

Foreign exchange, at the intersection of risks

The external vulnerabilities of emerging countries generally manifest themselves in downward pressure on their currencies against the USD, situations that have led to currency crises in the past. Furthermore, following an increase in Fed funds rates, the USD tends to appreciate in effective terms, which reinforces the depreciation of emerging market currencies. Exchange rate depreciation has a direct impact on external balances, generally leading to: an increase in imported inflation (which threatens the real interest rate); increased investor mistrust, which generally results in capital withdrawals and/or higher risk premium requirements; a deterioration in repayment capacity for foreign currency-denominated debt, etc.

In 2021, most emerging market currencies faced downward pressure due to revisions in growth forecasts linked to waves of Covid-19, but also in response to rising long-term interest rates in the United States. In the chart above, all countries on the left side of the chart saw their currencies fall against the USD, with significant declines in Argentina (-29% on average), Turkey (-20% on average), and Brazil (-14% on average).

The Fed’s late announcement of its intention to raise interest rates suggests that the currency depreciation movements in 2021 were not solely anticipatory. As a result, further depreciation could be seen in 2022, particularly in countries with the most significant external vulnerabilities (such as those mentioned in the previous sections: Turkey, Argentina, and Sri Lanka in particular) or for idiosyncratic reasons (such as the manifestation of political risk in Ukraine, Russia, or Kazakhstan at the beginning of 2022).

Furthermore, currencies that were relatively unaffected in 2021 could experience a different situation in 2022, particularly when the exchange rate can be considered overvalued. The intuition here is that investors would be less inclined to invest and/or hold assets denominated in these currencies in their portfolios. Indeed, if they consider them to be overvalued, the probability of their value being corrected downwards is theoretically higher than for undervalued or balanced currencies. These are the countries at the top of the graph, those with the highest real effective exchange rates[12]: Egypt, China, Ukraine, India, and the Czech Republic, for example. Conversely, countries with exchange rates that are a priori undervalued (Colombia, Russia, and even Brazil) would present more attractive investment profiles, all other things being equal.

Lower risk than in 2013 but increased vigilance in 2022

Since the events of 2013, markets have been better able to anticipate the Fed’s actions, thanks in particular to improved communication from central banks (notably via forward guidance). This suggests that any capital outflows from emerging countries would be more spread out over time and less significant, barring any « surprises » (such as an acceleration in the rate hike schedule or larger-than-expected hikes of more than 25 basis points at a time). Conversely, if there are fewer rate hikes than anticipated, the level of risk should decrease.

However, several emerging economies appear to be particularly exposed in 2022. In addition, the current economic environment remains challenging in most emerging countries: health uncertainties and their impact on economic activity, inflationary pressures, reduced monetary and fiscal room for maneuver as the crisis ends, high social and geopolitical risks, etc.

Not all emerging countries necessarily have sufficient buffers to cope with additional tensions in 2022. In this regard, some countries (Brazil, Chile, Hungary, Russia, and Turkey) have already seen their sovereign bond spreads widen in late 2021/early 2022 compared to pre-COVID-19 crisis levels, a sign of increased risk perception. Inflation management will likely be key, as its implications pose a much greater risk than in developed countries.

[1]A decision motivated by persistent inflationary pressures, a tight labor market, or the position in the economic cycle (closure ofthe output gap).

[2]Although no timetable has been announced at this stage, the consensus is for a rate of around 0.9% at the end of December 2022, compared with a rate of around 0% at the end of 2021.

[3]Investments in emerging countries are made in particular via indices such as the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, which lists and weights the most important emerging market stocks.

[4]Caused in particular by rising commodity prices (especially energy and food), supply shortages and a rebound in private consumption as health measures are lifted.

[5]The real interest rate in a country is generally measured by the difference between the nominal interest rate (i.e., the key rate set by the central bank) and the level of inflation.

[6]External financing requirements can be approximated by the sum of the current account deficit and external debt amortization.

[7]Based on forecasts by the World Bank (external debt amortization) and the IMF (current account balance).

[8]This strategy pays off when interest rates are particularly low and there is global excess liquidity in a currency, as was the case with the USD and the euro in the 2010s.

[9]Otherwise, they borrow at shorter maturities and/or with higher risk premiums.

[10]For monetary policy operations (to stabilize the local currency exchange rate), to have sufficient liquidity to meet external commitments (payment of imports, repayment of foreign currency debt), etc.

[11]The few countries that have seen their currencies appreciate are mainly countries with managed floating exchange rate regimes (Egypt, Morocco, and China to a lesser extent).

[12]This indicator is probably not the best proxy for assessing the over/undervaluation of an exchange rate, but it has the advantage of being available for a large number of countries on a monthly basis.