Abstract:

· The Paris Agreement is undoubtedly a major diplomatic success, but may seem illusory in certain respects.

· The goal of reducing fossil fuel consumption to limit global warming to 2°C would be difficult to achieve given current oil and coal prices.

· The goal could still be achievable with an international carbon pricing mechanism, which would also lend credibility to the promise to transfer a minimum of $100 billion per year to less developed countries.

· However, the timeframes for these transfers have not been sufficiently addressed.

The Paris Agreement was approved on December 12, 2015, at the end of COP 21, by world leaders in an effort to combat climate change. Is this agreement « historic »? There is no denying that the Paris Agreement was a great diplomatic success. For the first time, the United States, which boycotted the Kyoto Agreement in 1997, and China, which refused to impose an identical « carbon peak » for the most advanced countries and developing countries at the Copenhagen COP in 2009, actively participated in the negotiations. Also for the first time, an agreement of this kind is a symbol that the whole world has become aware of global warming. It thus creates a sense of urgency to respond at all levels and in all countries.

However, it is still too early to say that COP 21 in Paris is truly a « historic » agreement because, despite its diplomatic fanfare, it is much less clear what concrete changes the agreement can bring about in terms of the catastrophic trajectory of global warming. It will take a few years before we can assess the credibility of the transformation of these political intentions into effective commitments. At this stage, it is essential to question many elements that have not been addressed in the Paris Agreement and/or that risk causing false pretenses.

The « -2°C » target: What future for fossil fuels?

Article 2 of the agreement sets the goal of limiting the increase in global average temperature to less than 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C for the long term. This implies a need to switch to non-carbon energy sources by replacing a large part of coal (the fossil fuel that emits the most CO2), oil, and natural gas. Is this so obvious?

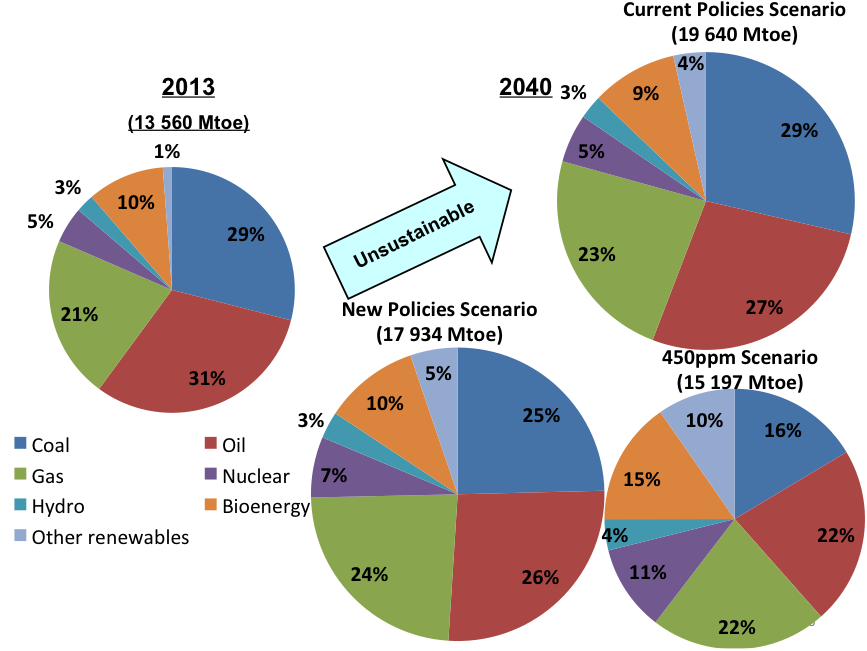

In the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) 2015 annual report, oil, coal, and natural gas account for more than 80% of our current energy consumption. The IEA also constructs different scenarios for the global energy balance over the next 20, 30, or 50 years. In the reference scenario, which corresponds to a situation in which no fundamental changes will be made from 2015 onwards, our energy consumption would increase by 45% in 2040 and fossil fuels would still account for nearly 80% of our consumption. This trend would be simply unsustainable if we take into account the impact on climate change caused by greenhouse gases emitted by fossil fuels. In the « New Policies » scenario, where certain climate policies would be implemented (post-COP21)[1], global consumption of these energy resources would remain largely unchanged in the face of rapid global population growth and demand from emerging countries. Only in the « 450 ppm » scenario[2] would the share of fossil fuels decrease to 60% with a significant reduction in coal consumption.

Figure 1. Global energy balance

Sources: Author, based on data from the IEA (2015) and BSI Economics

Halving the share of global coal consumption: mission possible?

The answer to this question is uncertain, as it would depend on the willingness of each consumer country, which varies from one country to another. It is all the more difficult to achieve this goal in a world where polluting is virtually free and where fossil fuel subsidies have been abundant—issues we will return to later.

Coal currently accounts for 29% of global consumption and 41% of global electricity production. The five largest coal consumers (China, the United States, India, the European Union, and Japan) account for 82% of global consumption. China, whose demand for coal accounts for half of global demand, plans to reduce the share of coal in its energy mix by 55% by 2030 (National Energy Administration (NEA), 2015). While reducing the Chinese economy’s dependence on this energy source is essential for the global climate, it should be noted that Chinese demand for coal is expected to reach a level slightly below its current level rather than decline rapidly (Cornot-Gandolphe [2016]).

In the United States, the shale gas revolution of recent years has enabled coal to be replaced by gas in the country’s energy mix. While this reduction in demand has led to a significant decrease in global coal consumption, it has also led to a significant drop in the price of this energy source, which in turn has caused a brief « coal renaissance » in Europe. In Germany, for example, despite the goal of reducing the share of coal through the massive development of renewable energies, coal consumption has remained virtually stable in recent years. It seems that coal will continue to be a significant component of the country’s energy balance, given that it is three times cheaper than natural gas.

In addition to these three major contributors (China, the United States, and the EU), there is India, the world’sthird-largest consumer of coal andfourth-largest emitter of greenhouse gases. In India, as in many emerging countries, despite ambitious targets for the development of renewable energies, coal consumption is expected to grow significantly as a result of economic and social development, as well as urbanization and industrialization.

In Japan, coal consumption rose sharply following the Fukushima disaster, when the country resorted to all fossil fuels to replace its nuclear power plants, which accounted for 30% of the electricity mix in 2010. It should be noted that this increase is likely to continue, as coal is considered essential to the country’s security of supply. Japan’s policy on this energy source provides for significant support for projects to finance new power plants, which extend to virtually all ASEAN countries.

Fall in oil prices: A new era of oil abundance?

Contrary to the predictions of many experts, the price of a barrel of oil plummeted to around $30 in the last days of January 2016, its lowest level since the global financial crisis in 2008. This spectacular drop in price was due to abundant supply from US shale oil and weak demand in many OECD countries, particularly the EU and Japan (emerging countries, notably China, are also experiencing a slowdown in demand). Adding to the complexity of these new market configurations are the political, geopolitical, and commercial challenges facing oil-exporting countries (OPEC), particularly Saudi Arabia. Indeed, some analysts believe that the decision to maintain production at a stable level and not to halt the fall in prices is probably a gamble by Saudi Arabia to eliminate investment in the most expensive units on the oil market, primarily US shale oil, which currently requires a price of between $45 and $75 to be profitable (Aoun, M-C. [2015]). However, shale oil has proven to be much more resilient than expected thanks to technical advances that have enabled continuous productivity gains for decades.

It is therefore difficult to predict how oil prices will evolve in the coming years. Uncertainty dominates this market, on both the supply and demand sides, compounded by the market power and political stakes of oil-producing countries, which, unsurprisingly, are the last to commit to the fight against greenhouse gases and global warming. What is certain is that if oversupply persists in the short term, as confirmed by the IEA, it will be difficult to promote less polluting means of transport as long as gasoline prices suit consumers. If, hypothetically, the average price of oil were to remain at $50 until 2020, the goal of reducing fossil fuel consumption would be even more difficult to achieve over the next five years, especially since the price of oil drives the prices of other commodities, such as gas and coal. Uncertainty surrounding carbon energy prices will not facilitate economic calculations on investments in energy sectors—tens of trillions of dollars in the hope of reversing the CO2 emissions curve.

Carbon pricing: still a long way to go?

While radically reducing coal and oil consumption over the next decade remains illusory, as the analysis below shows, the collapse of the long-term CO2 quota market and the unwillingness of leaders to save it offer even less hope for a reduction in polluting energies.

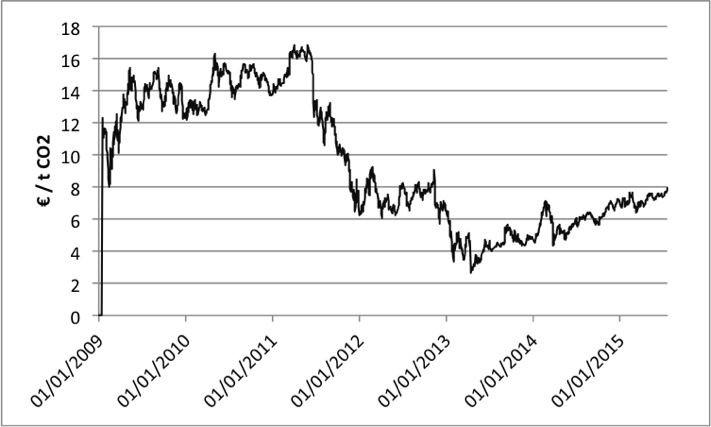

Figure 2. The evolution of European CO2 quota prices (2009–2015)

Sources: Author, European Energy Exchange, and BSI Economics

The price of carbon in Europe – the « pollution cost » – has fallen since 2009 to a ridiculously low level under both economic and political pressures: €0.2/ton of CO2 in 2009 compared with the former benchmark of €25 (average 2005–2008). While carbon prices are around €7/ton in 2015, a level above €30/ton would be needed to encourage the substitution of coal by gas at current energy prices (Cornot-Gandolphe [2016]). The use of the atmosphere is therefore virtually free, not to mention the abundant subsidies for fossil fuels around the world. In 2008, for example , $550 billion was spent on subsidizing the use of fossil fuels, twelve times more than the amount spent on supporting renewable energies (IEA [2009]). To sum up this situation in a few simple words: instead of making polluters pay, we are subsidizing them!

Faced with the difficulties encountered in implementing quota markets, economists (Stiglitz, Stoft) have recommended organizing negotiations between countries on the price of carbon rather than on emission caps. In the recent report by De Perthuis et al. (2015) by the Climate Economics Chair, the authors emphasize the importance of ending the fragmentation of CO2 quota markets around the world and introducing an international carbon « bonus-malus » mechanism which, in principle, aims to make polluters pay (at a true value) and reward those who do not pollute. The proposal seems simple enough to make the goal of limiting global warming to below 2°C still achievable. The Paris Agreement would have been a great success if it had paved the way for decisive progress in this direction.

What about the $100 billion per year for third world countries?

While the Kyoto Protocol limited emission reduction commitments to industrialized countries, the Paris Agreement succeeded in binding all countries into the commitment system under the auspices of the United Nations. The outdated vision of the » Kyoto era « is no longer credible in a new world where per capita CO2 emissions in China are as high as those in Europe and the United States, and where climate change knows no borders. The Paris Agreement thus aims to resolve the dilemma between emerging countries, which on the one hand will be hungry for energy for their demographic expansion, economic growth, and wealth creation, and developed countries, which on the other hand defend their wealth and interests and are not prepared to give up their comfort.

Article 9 of the agreement thus provides that rich countries commit to transferring $100 billion to less developed countries from 2020 onwards to finance their emissions reductions. This sum is certainly promising, but nothing in the 31 pages is specific about the nature of this funding. It is not clear whether these will be loans or grants, whether interest will be charged, whether the money will come from public funds or private investment, or whether there will be penalties for non-payment. And beyond this famous sum of $100 billion (which was promised in 2009 at the Copenhagen conference but which, to date, seems far from being raised), the real question to ask is: what are the long-term prospects? $100 billion per year for a decade seems inexpensive if it could save our planet (compared to annual subsidies for fossil fuels), but if it cannot, how long could this financial flow be guaranteed? It is therefore essential to find a mechanism that works in the long term.

A large part of the solution is linked to the global pricing mechanism with a bonus-malus system proposed by De Perthuis et al. (2015). According to the logic of this mechanism, countries with emissions above the average per capita emissions would have a debt to the community, and countries with emissions below the average per capita would have a credit. The authors estimate that, with a price of $1/ton of CO2, more than $10 billion per year would be transferred to the least developed countries, and that a price of $7/ton of CO2 would finance annual transfers of $100 billion—the amount corresponding to the financial transfer commitments in the Paris Agreement.

Conclusion

The 2015 Paris Agreement succeeded in binding all countries to the system of commitments with encouraging targets. Nevertheless, illusions remain. The goal of limiting global temperature rise to less than 2°C requires a radical reduction in fossil fuel consumption. However, it is unrealistic to think that coal will quickly disappear from the global energy mix in the coming decades, let alone oil, especially since the fall in oil prices does not make the task any easier. The Paris Agreement’s goal could still be achieved with an international carbon pricing mechanism, which would also lend credibility to the promise to transfer a minimum of $100 billion per year to less developed countries. However, this has not been sufficiently addressed.

The Paris Agreement sets out an official, universal agenda for the climate and the environment. It helps to legitimize the fight against climate change on a very broad scale. It relies solely on the goodwill of countries, so incentives need to be created to promote this goodwill. Otherwise, in 10 years’ time, we will still be waiting for another « historic » agreement that will solve all the problems.

Reference

IEA (2009, 2015) World Energy Outlook, International Energy Agency.

Aoun, M-C. (2015), A new era of oil abundance?, IFRI, Foreign Policy, 4:2015.

Cornot-Gandolphe, S. (2016), COP21: Down with coal, IFRI Note, January 2016.

Crampton, P., A. Ockenfels and Steven Stoft, (2015), An International Carbon-Price Commitment Promotes Cooperation, Economics of Energy and Environmental Policy 4.

DePerthuis, C., Jouvet, P-A., Trotignon, R. (2015), Carbon pricing: Options for post-COP21, Policy Brief, Climate Economics Chair, November 2015.

National Energy Administration (NEA), 2015, China’s Coal Supply and Future Development.

Stiglitz, R., (2015), Overcoming the Copenhagen Failure with Flexible Commitments, Economics of Energy and Environmental Policy 4.

Notes

[1]The « New Policies » scenario takes into account the political commitments and plans that have been announced by countries, including national commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, even if the measures to implement these commitments have yet to be identified or announced.

[2]The 450 ppm scenario establishes an energy balance compatible with the goal of limiting the global temperature increase to 2°C by limiting the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere to approximately 450 parts per million of CO2.