Summary

– In times of crisis, indebted businesses and households tend to prioritize repaying their debts in order to strengthen their financial position, which does not promote a rapid economic recovery.

– In the eurozone, some countries such as Ireland, Portugal, and Spain have high levels of private debt and non-performing loans. The rise in bad debt, coupled with an unfavorable business climate, is prompting banks to restrict lending despite low demand.

– The contraction in private demand through the feedback loop is likely to keep economic activity sluggish.

– Accumulating debt creates a confidence deficit that harms economic activity.

Triggered in the United States by the bursting of a real estate bubble (the subprime crisis) in 2007, the economic crisis currently affecting Europe is a public debt crisis. However, the maturing of the financial crisis has nothing to do with a public finance problem; the level of sovereign debt jumped after the crisis became systemic and systematic (public debt ratios in Eurozone countries only began to rise in the third quarter of 2008).

In theory, private debt is pro-cyclical, increasing during periods of economic boom (investment, consumption) and decreasing or stagnating in times of crisis. At the same time, public debt, which is counter-cyclical, partially offsets the fall in private investment during recessions; public debt increases in order to stimulate consumption and public investment and to recapitalize banks in crisis.

However, the economic slump that Europe is currently experiencing is longer and deeper, and the recovery is slower. How does the level of private debt affect the duration of the recession and the path out of it? Is public debt solely responsible for a weak and difficult recovery?

1–The increase in private debt in Europe

In the years following the 2008 economic crisis, private debt-to-GDP ratios increased in Europe due to:

– tighter credit conditions,

– the rapid accumulation of private debt, leading to a need for external financing that increased countries’ vulnerability to a contraction in capital inflows,

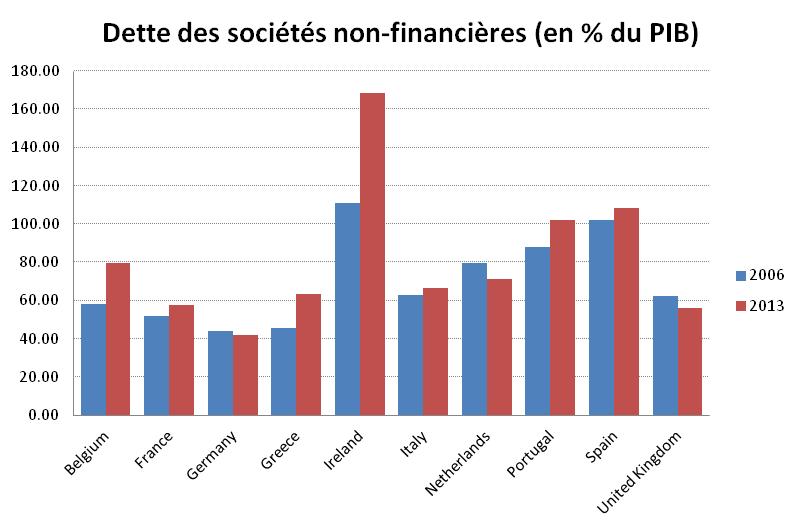

– the inefficiency of the credit channel[1]the ECB’s monetary policy: the fall in key interest rates from 1.50% to 0.05% between July 2011 and September 2014 does not appear to have encouraged the consolidation of non-financial companies’ balance sheets in the euro area (Chart 1)

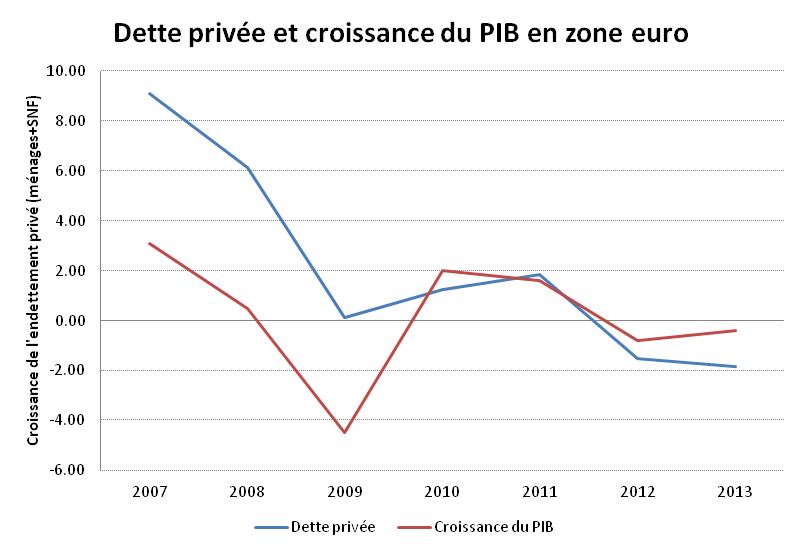

– a contraction in GDP, which automatically increases the debt-to-GDP ratio. Economic growth is closely linked to changes in private debt (see Chart 1). Thus, sluggish economic activity would not promote a reduction in private debt (Chart 2).

Chart 1 – Non-financial corporate debt in Europe

Sources: OECD, Macrobond, BSI Economics

Chart 2 – Growth in private debt as a percentage of GDP in the eurozone

Sources: OECD, Macrobond, BSI Economics

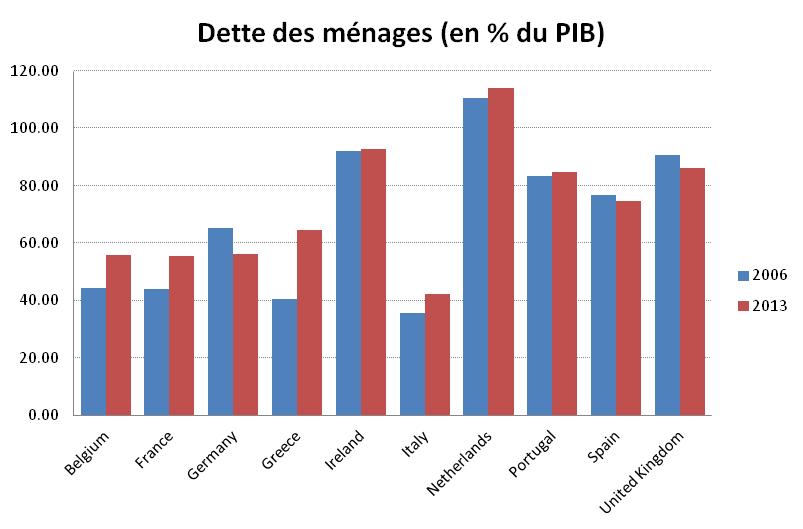

Chart 3 – Household debt in Europe

Sources: OECD, Macrobond, BSI Economics

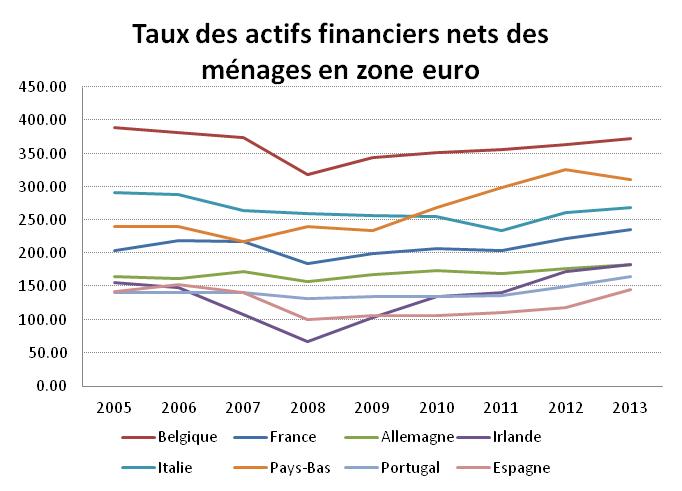

Chart 4 – Household net financial asset ratio

Sources: Eurostat, Macrobond, BSI Economics

Ireland, Spain, and Portugal in particular have high levels of private household and corporate debt, exceeding 200% of GDP.

Household debt is particularly high in Ireland, Portugal, and the Netherlands, where it exceeds 100% of GDP, which can affect household solvency when assets are low (in France, households are heavily indebted but assets are high, so net assets do not affect the solvency of French households, see Figure 4). The Italian private sector has low debt despite a very high public debt-to-GDP ratio. This does not mean that Italian companies are doing well: 30% of private debt is held by companies whose pre-tax income is lower than the interest they have to pay.

Weak corporate balance sheets combined with high levels of debt make European companies reluctant to invest in new projects, while commercial banks are reluctant to grant loans and prefer to focus on recycling their non-performing loans.

2 – First effect of private debt: the feedback loop

The contraction in private demand caused by the feedback loop would maintain sluggish economic activity.

Indebted private agents are vulnerable to sudden shocks in asset prices or interest rates. Indeed, in a context of high private debt, a crisis can put pressure on agents’ balance sheets, either by devaluing the price of certain assets (e.g., real estate prices) or by increasing certain liabilities (e.g., interest rates on loans). In this case:

– households do not take out new loans, draw down their savings or default on their loans in order to avoid a sharp drop in consumption,

– businesses focus on strengthening their balance sheets, reducing debt, and cutting back on investment[2].

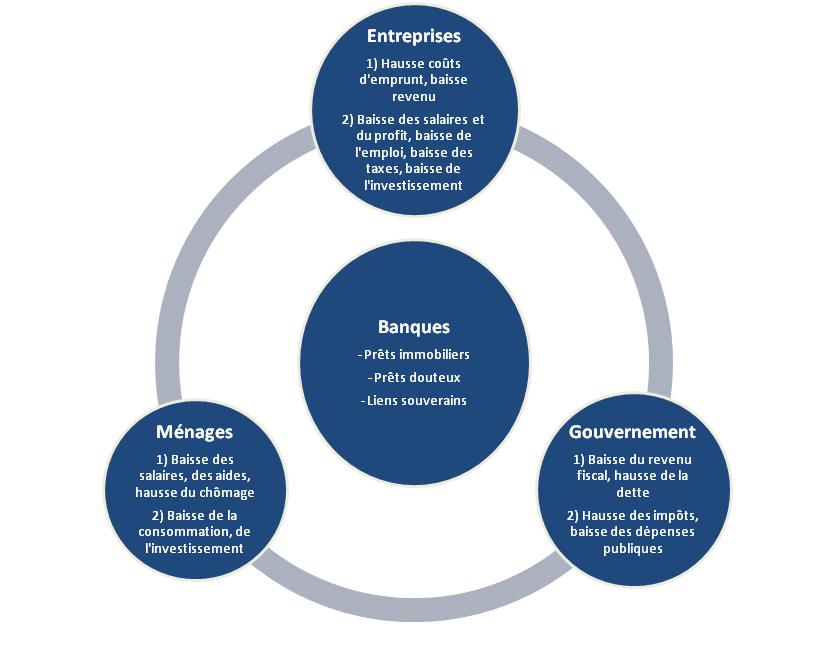

This behavior results in a decline in private demand, which creates feedback loops in certain sectors and exacerbates the crisis:

– Indebted households consume and invest less, which reduces corporate profitability and tax revenue[3].

– Faced with a decline in household demand, businesses cut costs by reducing wages and restructuring their investments in an attempt to maintain or increase their margins, which they use to reduce their debt. In turn, this behavior reduces household income and increases unemployment, further reducing government tax revenue.

– The government, itself keen to reduce public debt, increases tax revenues by raising taxes and reducing public spending. However, this tax increase weighs on households’ disposable income (and therefore on their net debt and their ability to repay) and on the investment capacity of private companies.

– Faced with an increase in bad loans from households and businesses, and an increase in risk premiums on sovereign debt bonds, commercial banks consolidate their financial positions by limiting access to new credit through more restrictive access conditions.[4]. In turn, this behavior is reducing investment demand.

Figure 4 – The private debt/economic growth feedback loop

3 – Second effect of private debt: the confidence deficit

Accumulating debt creates a confidence deficit that harms economic activity.

The increase in private debt stock contributes to increasing the sensitivity of an agent’s solvency to a possible change in their income or interest rates. In addition, a larger stock of private debt increases the risk premium and contributes to a tightening of credit conditions by creditors. These two effects are amplified by a sharp rise in the rate of bad debts.

Several academic articles have shown that a large volume of private debt has a negative effect on economic activity, which can be even more significant in times of recession:

– a study by the BIS[5]of 18 OECD countries shows that private debt exceeding 90% of GDP for non-financial corporations and 85% of GDP for households has a negative impact on economic growth.

– An IMF report[6]shows that high private debt would be more detrimental to economic growth than high public debt: a country with high private debt and high public debt would experience a sharper fall in GDP and household consumption, a more pronounced rise in unemployment, and a longer recession (five additional years) than a country with high public debt but low private debt.

Conclusion

While the crisis currently affecting Europe is a sovereign debt crisis, its private counterpart seems to be the cause of a deepening recession: sluggish consumption, low investment, uncertainty among creditors and borrowers, monetary policies that are struggling to deliver results, and austerity measures.

Europe must resolve its private debt problem if it hopes to achieve a sustainable recovery. This would require an inventory of non-performing loans, which banks swept under the rug during their recapitalization but which remain on their balance sheets and increase risk and uncertainty, preventing the flow of new credit.

Notes:

[1] Creel, J., P. Hubert, and M. Viennot, 2013. “Assessing the interest rate and bank lending channels of ECB monetary policies,” Technical report, Sciences Po Department of Economics.

[2] Bonhorst F. and M. Arranz, 2014. “Growth and the importance of sequencing debt reductions across sectors,” Chapter 2 in Debt in the Euro Area, IMF Publications.

[3] Bonhorst F. and M. Arranz, 2014. “Growth and the importance of sequencing debt reductions across sectors,” Chapter 2 in Debt in the Euro Area, IMF Publications.

[4] Creel, J., P. Hubert and M. Viennot, 2013. “Assessing the interest rate and bank lending channels of ECB monetary policies”, Technical report, Sciences Po Department of Economics.

[5] Bank for International Settlements, Cecchetti S.G, M.S. Mohanty and F. Zampolli, 2011. “The real effects of debt”, BIS Working Papers, No. 352, September.

[6] Bonhorst F. and M. Arranz, 2014. “Growth and the importance of sequencing debt reductions across sectors,” Chapter 2 in Debt in the Euro Area, IMF Publications.

References:

– Blot, C., J. Creel, P. Hubert and F. Labondance, 2015. “What can we expect from the ECB’s quantitative easing?”, Revue de l’OFCE, 138(2015)

– Bonhorst F. and M. Arranz, 2014. “Growth and the importance of sequencing debt reductions across sectors”, Chapter 2 in Debt in the Euro Area, IMF Publications.

– Cecchetti S.G, M.S. Mohantyet F. Zampolli, 2011. “The real effects of debt,” BIS Working Papers, No. 352, September.

– Creel, J., P. Hubert, and M. Viennot, 2013. “Assessing the interest rate and bank lending channels of ECB monetary policies,” Technical report, Sciences Po Department of Economics

– International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2013. “Fragmentation, the Monetary Transmission Mechanism and the Monetary Policy in the Euro area”, Chapter 1in Euro Area Policies: Selected issues, Country Report No. 13/232

– International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2012. “Chapter 3: Dealing with household debt,” World Economic Outlook Report, April

– Liu Y. and C.B. Rosenberg, 2013. “Dealing with private debt distress in the wake of the European financial crisis: a review of the economics and legal toolbox”, IMF Working Paper, No. 13/44