Summary:

– Slovenia has been experiencing a severe economic recession since 2012. This trend is expected to continue in 2014 with a smaller decline of around 0.1% of GDP amidst a recovery in the Eurozone.

– This recession is taking place against a backdrop of fiscal consolidation, made necessary by Slovenia’s commitments under the excessive deficit procedure.

– The banking sector remains in a generally poor state and continues to weigh on Slovenia’s public finances. The results of the external audit, finally unveiled on December 12, 2013, reassured the markets by putting the banking sector’s recapitalization needs in the adverse scenario at €4.8 billion (13% of Slovenian GDP), an amount in line with analysts’ expectations.

– Debt reduction in the real sector remains a major challenge in terms of sustainable banking sector consolidation. The country has begun the privatization process, which should enable the state to withdraw. However, obstacles, particularly political ones, make the process delicate and uncertain.

Slovenian Prime Minister Alenka Bratusek reiterated this in December 2013 after the results of the external audit of the banking sector were announced: Slovenia will not become the next country after Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and more recently Cyprus to resort to a financial rescue program. Slovenia simply needs time to clean up its banking sector and consolidate its public finances. This view is shared by the European Commission, which, as part of the excessive deficit procedure, has agreed to extend the deadline for the country to bring its deficit below 3% of GDP by two years.

However, the Slovenian case was the subject of much discussion within European institutions in the second half of 2013, with fears of a new bout of weakness within the eurozone and a potential knock-on effect. Although market tensions have eased somewhat, Slovenia’s economic situation remains uncertain, as the restructuring of the banking sector, the consolidation of public finances, and the withdrawal of state support are far from complete and are weighing on the recovery.

1. From a banking crisis to a deterioration in public finances

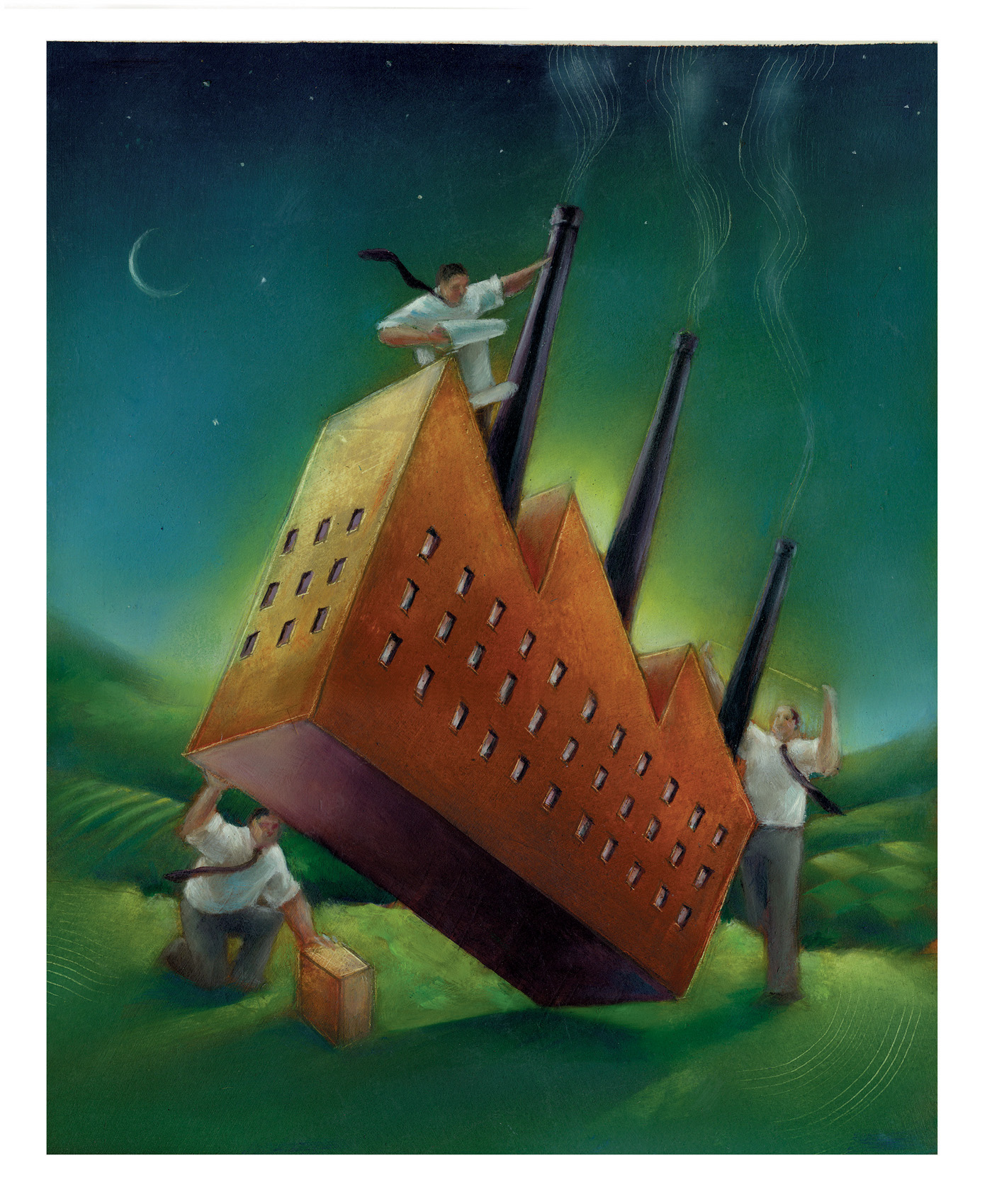

At the heart of the Slovenian crisis lies the interrelationship between the private and banking sectors, both of which have a strong public component, a legacy of the economic transition model chosen by Slovenia after its independence. This interlocking of shareholdings between companies and public banks has led to political interference, resulting in poor governance and a certain laxity on the part of supervisory bodies. This interconnection also contributed to creating, during the expansion phase in the early 2000s that led to the country’s entry into the euro zone in 2007, the conditions for excessive private sector debt and excessive risk-taking by the banking sector.

The deterioration in asset quality when the economy turned down then forced the main banks and public companies to recapitalize, putting pressure on public finances. This deterioration in assets stemmed mainly from private corporate debt, which was heavily concentrated among a few creditors. At the end of August 2013, the 40 largest loans accounted for 34% of total non-performing loans (NPLs), with the next 200 loans accounting for 33% of the total. At the sectoral level, Slovenia’s main banks (publicly owned) are suffering from their heavy exposure to the construction sector (62% of loans in this segment were recorded as non-performing at the end of 2012).

Thus, while public finances appeared relatively healthy before the financial crisis, with public debt at 22% of GDP in 2008 and a budgetary position close to balance, the economic stimulus measures in 2009 and the burden of financial support for public banks have significantly changed the situation. Public debt more than doubled to reach 55% of GDP at the end of 2012 and is expected to approach 70% after the recapitalization of the banking sector is completed. The deficit is expected to exceed 4% of GDP (excluding the cost of bailing out the banks, 7.1% including this cost) in 2013, despite the significant consolidation efforts made by the government since 2010. Uncertainty about the health of the banking system and its impact on public finances is leading, as in Portugal and Ireland, to speculation about the real extent of the banking difficulties and the country’s ability to finance this restructuring. These fears, reflected in the markets by tighter financing conditions, have led the country into a self-fulfilling spiral of banking crisis coupled with a sovereign crisis.

2. Bank restructuring and consolidation: necessary priorities for the government in the face of growing market pressure.

The improvement in Slovenia’s economic outlook therefore depends on the government’s ability to stem the deterioration of the banking sector and convince the markets of the credibility and sustainability of the measures taken.

The results of the asset quality review (AQR) and stress tests (ST) unveiled on December 12, 2013 appear reassuring in this regard. The review, covering eight banks and 70% of the banking sector’s assets, estimated the recapitalization needs in the adverse scenario at €4.8 billion, or 13% of Slovenia’s GDP, of which €3 billion is earmarked for the three largest Slovenian banks (NLB, NKBM, and Abanka). Two-thirds of the recapitalization of the three banks mentioned will be financed in cash from the state’s financial reserves and one-third through new bond issues. This will raise the solvency ratio (Tier 1) to over 15% for NLB and NKBM and 9% for Abanka. The three banks also imposed losses on subordinated bondholders (bail-in) amounting to €441 million and transferred €4.6 billion of non-performing loans to the bad bank (BAMC) for a fixed price of €1.6 billion in order to clean up their balance sheets. The non-performing loan (NPL) ratio of these three banks reached 24.5% at the end of August, with a more pronounced deterioration in private corporate loans (38.5% NPL), mainly concentrated in the construction and manufacturing sectors.

These initial recapitalizations, combined with the preventive restructuring of two banks, Probanka and Factorbanka, and a €200 million capital increase for BAMC, seemed to convince the markets. This is reflected in the decline in Slovenian bond yields, with the spread with Spain and Italy, which have similar ratings, narrowing to 100 basis points after the AQR results, compared with 200 basis points at the peak of speculation about the health of the banking sector. In addition, after simultaneously downgrading Slovenia’s rating in 2012, the rating agencies, in the case of Moody’s, changed their outlook from negative to stable in early 2014 and raised the ratings of the three banks NLB, NKBM, and Abanka, in line with the progress made in stabilizing the banking sector.

Finally, on February 10, 2014, Slovenia returned to the bond markets by placing $3.5 billion (2 billion in 10-year bonds and 1.5 billion in 5-year bonds), an offer higher than the 2 to 3 billion initially announced by the government. Strong demand (over $16 billion) and lower rates compared to the last issue in May 2013 (5.48% vs. 6% for 10-year bonds and 4.275% vs. 4.95% for 5-year bonds) demonstrate renewed interest from investors (mainly American and British) after a difficult year in 2013 in terms of access to financial markets. Faced with pressure on rates in Europe, Slovenia took advantage of greater liquidity in dollar-denominated markets and carried out several dollar-denominated issues during 2013.

However, this recapitalization of the banking sector is weighing on public finances. Debt is expected to continue to grow, reaching 70% of GDP in 2014, making it necessary to extend consolidation efforts. In this regard, the 2014 budget, which was narrowly passed in mid-November (along with a vote of confidence in the Bratusek government), is based on a deficit assumption of 3.5% of GDP, leaving little room for maneuver for the government in the event of weaker-than-expected fiscal performance or further turmoil in the banking sector. The tax-to-GDP ratio is expected to increase in line with the highly controversial new property tax, while the main measures on the expenditure side consist of a freeze on pensions and social benefits in 2014 and 2015 and a further reduction in public sector wages. At the structural level, the government will have to address the segmentation of the labor market linked to excessive protection for those in employment and deepen the pension reform passed at the end of 2012 to better take into account the rapid aging of the Slovenian population.

3. Private sector deleveraging and state disengagement: a delicate solution to the underlying problems of the Slovenian economy.

However, the measures mentioned above should not obscure the need to resolve the intrinsic problems of the Slovenian economy, namely corporate deleveraging and the withdrawal of the state, which is currently less well underway.

Since 2009, the performance of the private sector has deteriorated significantly, with profit margins at a historic low of close to 1%. Slovenian companies are suffering in particular from excessive debt, with a debt-to-equity ratio of 135%, down from 2009 but still well above other countries in the eurozone, thereby hampering the recovery of investment. In this regard, the new bankruptcy procedure proposed by the government is a crucial step forward, dismantling a lengthy (four years on average), costly, rigid procedure that is unsuitable for rehabilitating viable assets. This restructuring effort should also be facilitated by the BAMC, although the issue of the structure’s governance and operational independence remains to be proven.

The necessary deleveraging of Slovenian companies with a view to returning to growth is nevertheless likely to penalize investment in the short term, particularly in the absence of foreign capital inflows. State interference and the complexity of the shareholding structure have discouraged foreign investment, depriving the country of new capital injections and technology transfers. Slovenia thus has one of the lowest rates of foreign direct investment (FDI) relative to GDP in Central Europe, even though it has a skilled workforce, high-quality infrastructure, and a strategic location in supply chains at the crossroads of Western, Central, and Balkan Europe. At the end of 2012, FDI inflows represented 34.1% of GDP in Slovenia, compared with 60.8% in Slovakia, 47.3% in Poland, 69.6% in the Czech Republic, and 81.6% in Hungary.

However, the state’s withdrawal, which is essential if it hopes to attract foreign investors, seems to be gradually taking shape thanks to the start of the privatization process. In November, Parliament approved a list of 15 companies to be privatized as a priority, including the main telecommunications company Tekelom, the NKBM bank, and Ljubljana Airport. By the end of January 2014, the government had already completed the sale of two companies (Fotona, a manufacturer of medical lasers, and Helios, a paint manufacturer). Nevertheless, doubts remain about the government’s ability to fulfill its commitment, as opposition to the sale of national assets remains strong and Slovenia’s political stability is fragile. In addition, the establishment of the new sovereign public assets agency (SSH), which is supposed to bring all public entities under one umbrella and clarify their governance, is dragging on, crystallizing the divergent interests of the various coalition parties.

4. An uncertain end to the crisis: persistent weakness of internal growth drivers, ongoing risks associated with the banking sector, and a precarious political balance.

Slovenia has been in a severe economic recession for eight consecutive quarters, with GDP declining by 2.5% in 2012 and, according to the latest European forecasts, by 2.7% in 2013. This trend is expected to continue in 2014, with GDP forecast to fall by 0.1% despite a recovery in the eurozone. In 2013, Slovenia’s real GDP fell by 11% compared with its pre-crisis level, the sharpest decline in the eurozone after Greece.

While Slovenia’s economic downturn in 2009 was mainly due to a sharp contraction in investment following a drying up of external financing caused by the financial crisis, the deepening recession since the end of 2011 has been driven by persistently weak consumption. The latter remains hampered by fiscal consolidation, stagnant wages, and high unemployment of close to 11% (double its pre-crisis level).

The latest indicators available at the end of 2013 do not point to a significant improvement in private consumption, with a persistent decline in retail sales, while stabilization of employment and wages is not expected to materialize until 2015. Weak domestic demand is accompanied by relatively moderate inflation (1.9% at the end of 2013 as measured by the IPHC) and a recurring current account surplus driven mainly by the trade balance and a reduction in imports. The latest short-term activity indicators at the end of 2013 nevertheless show encouraging trends, with manufacturing output stabilizing and a marked recovery in construction (still well below its pre-crisis level), alongside a slight improvement in economic agents’ expectations.

Thus, as in 2012, the only positive contribution to GDP growth in 2013 came from net exports. Accounting for more than 70% of Slovenian GDP, Slovenian exports are mainly directed towards the European Union (40% of GDP) and more specifically towards Germany (21.8% of total exports in the first half of 2013), Italy (11.7%), Austria (7.9%), Croatia (6.1%), and France (5.8%). From a sectoral perspective, Slovenian export sales are concentrated in motor vehicles (11.9% of the total in the first half of the year), pharmaceuticals (10.9%), and electrical machinery and equipment (9.5%). The recovery of the Eurozone could therefore benefit Slovenian exports by stimulating German demand in particular, as Slovenia is a major supplier to Germany’s main export industries. However, Slovenia’s main export sectors (automobiles and household appliances) are likely to continue to suffer from declining consumption in Europe in these segments. Only pharmaceuticals are benefiting from growing demand, driven in particular by the generics market, in which Slovenia is well positioned. In addition, the positive export trend (+3.8% forecast for 2014) masks stagnating price competitiveness in the Slovenian economy (linked in particular to wage increases outpacing productivity during the boom years) and a specialization in medium- and low-value-added goods that are relatively sensitive to competition from other Central and Eastern European countries.

Furthermore, despite a satisfactory start to the process of cleaning up bank balance sheets, there are still many risks. Firstly, the AQR conducted by the ECB in 2014 could change the situation, as the scope of the analysis is slightly different and includes SID, the Slovenian development bank. A new estimate of recapitalization needs could thus reignite the banking/sovereign spiral, once again threatening Slovenia’s ability to refinance itself, even though its financing needs for 2014 are estimated at €3.5 billion. In addition, the rate of non-performing loans remains a concern. It reached nearly 21% of total loans in October 2013 and is expected to fall to 12% after the transfer of bad debts from the three main banks, a level that is still high compared to the rest of Central Europe (10% on average for the region in 2012).

Finally, political stability remains a major challenge in Slovenia. Following the ousting of Prime Minister Janez Jansa (center-right) on corruption charges in February 2013, the formation of a coalition has been particularly turbulent. The coalition formed by Alenka Bratusek has only a very narrow majority and includes parties with differing interests, making the reform process relatively delicate and sometimes unpredictable (as shown by the example of the new property tax proposed by Bratusek, which was initially blocked by one of the coalition parties).

Conclusion

Thus, while the announcement of the results of the bank audit and the start of the privatization process seem to have temporarily reassured the markets, the Slovenian economy does not yet appear to be out of the woods. Growth is expected to remain sluggish in 2014, weighed down by weak domestic consumption, corporate deleveraging, and the fragility of Slovenia’s main partners. Finally, the country’s economic outlook will depend heavily on political factors and the coalition’s ability to achieve a « sacred union, » as the opposite could destabilize the country by reintroducing uncertainty in the markets.