Summary

-In Sub-Saharan Africa, the state has made land reform a key tool for promoting agricultural and rural development.

-The formalization of property rights over agricultural land is supposed to increase land security for agents and enable an increase in investment and agricultural productivity.

-Empirical studies on the links between land tenure security and agricultural investment/productivity have nevertheless produced mixed results.

-In many countries, however, land reform has led to an increase in land conflicts by fueling the continuing uncertainty surrounding land rights.

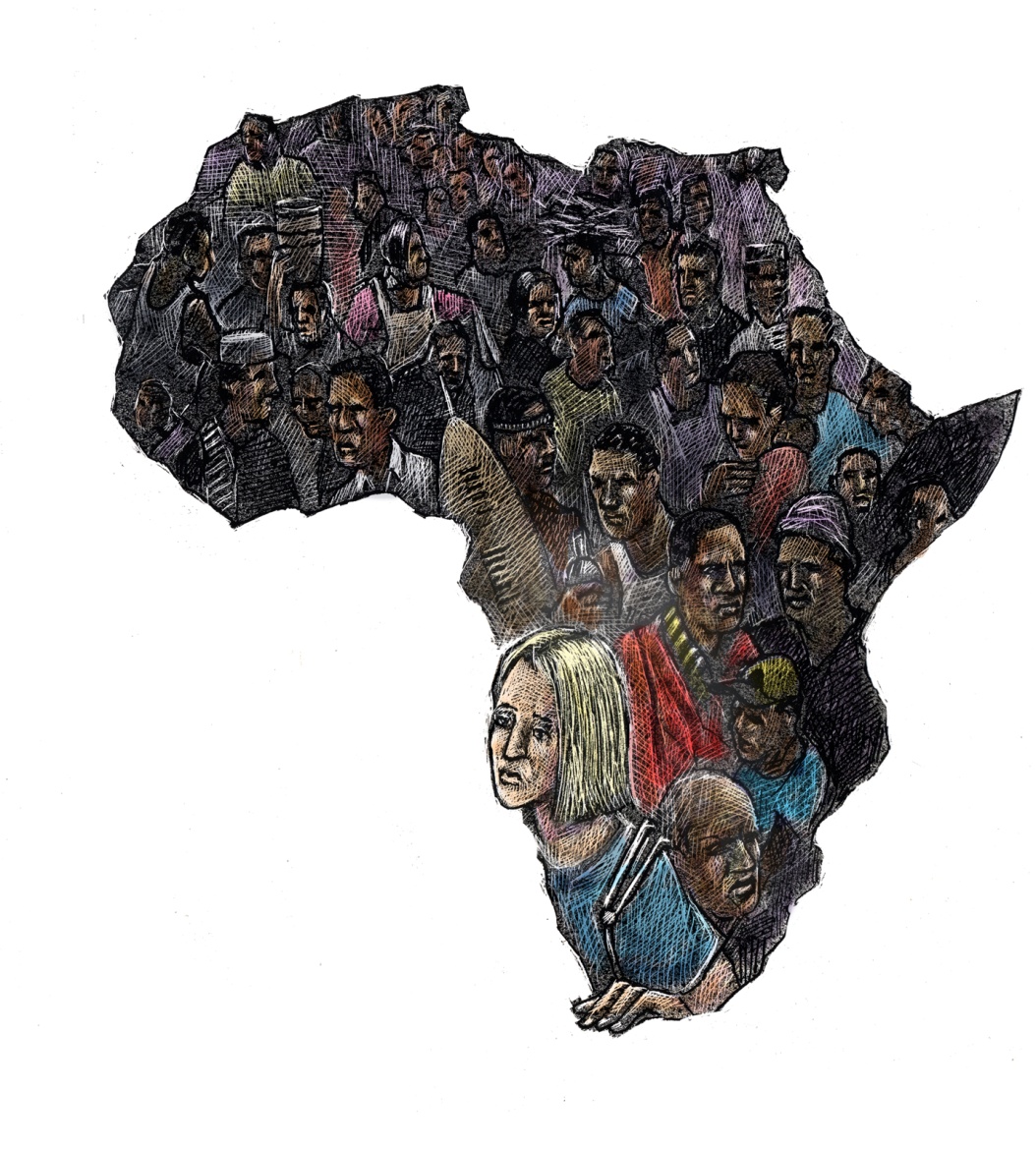

Against a backdrop of rapid population growth and increasing degradation of agricultural land, issues relating to increasing agricultural productivity (while preserving the environment) are more relevant than ever for many countries in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). For several decades, and particularly during the 1980s and 1990s with the implementation of structural adjustment policies, African governments, with the assistance of international donors, have made land reform the main tool for promoting land security and agricultural development as a whole.

Land tenure security, which is equated with private property rights and brought about by land reform, is supposed to influence the investments that are essential for increasing agricultural productivity and agricultural development as a whole. However, while there is a wealth of research on the relationship between land reform, land tenure security, investment, and agricultural productivity in SSA countries, the literature is far from unanimous on the positive impact of land reforms and private property rights in general on agricultural development. Given the direct (particularly financial) and indirect (land conflicts, etc.) costs of this type of operation on the one hand, and the multiple challenges facing African agriculture on the other, the need to carry out land reforms to promote agricultural development is a relevant issue for SSA countries.

Land security: a vague concept

While there is consensus on defining land security in terms of how agents perceive the degree of « security » of their rights to a plot of land, there is still some ambiguity about the content of the rights that are supposed to provide agents with enough security to invest, for example. In the African context, the coexistence of a traditional land tenure system and a formal legal framework governing land relations fuels this vagueness. Indeed, it should be noted that the concept of land tenure security is often associated with that of private property, effectively considering rights to use the land and/or the resources it bears (e.g., trees) as insecure. Given the importance of these rights in many African countries, this definition of land tenure security and the recommendations resulting from the work that adopts it contribute to disconnecting the formal framework governing land arrangements from the reality in African countries (see Lavigne Delville et al., 2001).

In addition, beyond the definition of land tenure security, different measures are used in studies estimating the impact of land tenure security on agricultural investment/agricultural productivity. However, the most commonly used measure remains the possession of a land title, which is supposed to represent the highest degree of security.

Through a review of the empirical literature, Arnot et al. (2011) highlight the differences that exist between how land tenure security is defined and how it is measured. They attribute these variations to a lack of information on preferable measures of land tenure security. Furthermore, the authors emphasize the difficulties in measuring land tenure security « correctly » and the confusion this can cause in terms of assessing the effects of land tenure security. Fenske (2010) analyzes several studies on land tenure security in West African countries and concludes that, depending on the measure used, the probability of finding a significant relationship between land tenure security and investment varies considerably.

Impact of « land security » on investment and agricultural productivity

Evolutionary theory of land rights (ETLR) (see Platteau, 1996) is the theoretical model of reference for studying the evolution of land tenure systems and its implications. Drawing in particular on the contributions of Boserup (1965) on the evolution of agrarian systems in pre-industrial societies, but also on those of the property rights school (see Demsetz, 1967), ETLR emphasizes the existence of a causal link between private property and agricultural investment. Under the influence of demographic and market pressures, there would be a spontaneous evolution of the land tenure system towards a system guaranteeing greater land security and, at the end of the process, private property. The latter is supposed to represent the most effective form of land regulation because it is conducive to agricultural intensification. This is because farmers are encouraged to invest, as they are sure of being able to benefit from the returns on their investments.

The state can also play an active role in the transition to a private property regime by establishing procedures for registering or issuing title deeds. This state intervention is considered necessary to compensate for the weakening of customary land management structures due to increasing demographic pressure and to respond to the growing demand from farmers for title deeds. Following this intervention, the theory anticipates the creation of a land market with a reallocation of land in favor of dynamic farmers and the development of a credit market, which is all the more beneficial to investment (Platteau, 1996). Implicitly, private property is considered the ideal form of land security, as it is economically efficient in the face of increasing demographic pressure and market development (Lavigne Delville, 1998).

This vision underpins many land reforms in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly the reforms carried out in the 1990s in the Sahelian countries (Lund, 2000). These reforms, which are part of a general context of structural adjustment, advocate the privatization of land, which is supposed to lead to land security and agricultural intensification.Their promoters also see this as a solution to the land conflicts that accompany the growing competition for land and which they claim demonstrate the inefficiency of customary land tenure systems. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the empirical literature is rather divided on the impact of land tenure security, and more specifically the holding of individual land titles, on agricultural investment in the African context (see, for example, Besley, 1995; Holden and Yohannes, 2002; Kabubo-Mariara, 2007). These mixed results could be explained in particular by the existence of an inverse relationship between land tenure security and agricultural investment (see, for example, Besley, 1995; Quisumbing et al., 2001; Brasselle et al., 2002).

In addition, several studies have highlighted the significant impact of other factors on agricultural investment and productivity. Indeed, as Lavigne Delville (1998) points out, land tenure security is often presented, in a simplistic manner, as the main, if not the only, factor determining agricultural intensification and, consequently, agricultural development. The role of important factors such as policies on access to credit or road infrastructure is often underestimated. In fact, a frequently cited study by Migot-Adholla et al. (1991) on several African countries (Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda) suggests that factors such as the lack of rural infrastructure are more limiting for agricultural intensification and the adoption of new technologies. The study by Ouédraogo et al. (1997) on Burkina Faso concludes that property rights have no impact on agricultural productivity and suggests that the latter depends mainly on natural soil fertility and climatic conditions.

Land reforms: the main driver of agricultural and rural development?

Do private property/land titles constitute the ideal degree of land security? Given the results of empirical studies in the African context, is it necessary and urgent to resort to such a costly instrument as land reform to promote agricultural development?

While empirical studies report a shift in traditional land tenure systems in the direction predicted by ETLR in several areas of the continent, most of the effects anticipated by the theory have not been confirmed in reality (Platteau, 1996). This is particularly true of the formalization of land rights, which has failed to increase land security for farmers or to promote the emergence of genuine land and credit markets.[1]. On this crucial point of access to credit, several studies highlight the importance of the « credit supply » side. More specifically, even with a land title, land does not constitute a secure guarantee for lenders in sub-Saharan African countries, for several reasons[2], it cannot be seized and/or sold in practice (Pinckney and Kimuyu, 1994).

Furthermore, according to several authors, state intervention often has the effect of increasing legal uncertainty around land issues. Lavigne Delville (2002) blames repeated state intervention for contributing to the proliferation of land tenure norms dating back to the colonial period and the interpenetration of « customary » and « state » norms, effectively increasing land insecurity, uncertainty, and conflicts (Lund, 2000). Numerous studies in African countries also highlight clientelistic relationships and corruption within public institutions, which can be a source of conflict and land insecurity even for people with land titles[3]. Platteau (1996) draws particular attention to the actions of elites, who manipulate the process of land rights allocation to their advantage.

Conclusion

In light of this observation, and even as land reforms aimed at promoting private ownership are multiplying, a growing number of studies are advocating for a shift in current land reforms, particularly toward more comprehensive agricultural policies (see, for example, Jayne et al., 2003; Lavigne Delville and Merlet, 2004) . In fact, in order to promote agricultural and rural development in sub-Saharan African countries, it is becoming urgent, on the one hand, to adapt land policies to local contexts, in particular through the recognition of customary institutions. On the other hand, it would be advisable to link these land policies to economic policies and support mechanisms for family farming, which would enable the latter to develop and modernize.

Notes:

[1] (1) On the impact of land title ownership and access to formal credit, see in particular the study already cited by Migot-Adhola et al. (1991). The authors find no significant relationship between the percentage of households receiving formal credit and the proportion of land held with full transfer rights.

(2) Popular resistance or the status of the borrower (relationships with politicians, etc.), the failure of the judicial system, etc. are often cited as reasons for the inability of lenders to seize and sell land in African countries (Platteau, 1998).

(3) See, for example, Bassett and Crummey, 1993; Chauveau and Lavigne Delville, 2002.

References

Arnot, C.D., Luckert, M.K., and Boxall, P.C., 2011, “What is tenure security? Conceptual Implications for empirical analysis, » Land Economics, Vol . 87, No. 2, pp. 297-311.

Bassett, T. and Crummey, D., 1993, Land in African Agrarian Systems, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison.

Besley, T., 1995, “Property Rights and Investment Incentives; Theory and Evidence from Ghana, » Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 103 , No. 5, pp. 903-37.

Bosrup, E., 1970, Agrarian Evolution and Population Pressure, Paris, Flammarion.

Brasselle, A.S., Gaspart, F., and Platteau, J.P., 2002, “Land Tenure Security and Investment Incentives: Puzzling Evidence from Burkina Faso, » Journal of Development Economics, Vol . 67, pp. 373-418.

Chauveau, J.P. and Lavigne-Delville, Ph.,2002, “Quelles politiques foncières intermédiaires en Afrique rurale francophone” (What intermediate land policies in rural French-speaking Africa), In Lévy, M. (ed.), Comment réduire pauvreté et inégalités : pour une méthodologie des politiques publiques(How to reduce poverty and inequality: towards a methodology for public policy), Paris, Karthala, pp. 211-239.

Demsetz, H., 1967, “Toward a Theory of Property Rights, » American Economic Review, Vol. 57 , No. 2, pp. 347-59.

Fenske, J., 2010, “Land tenure and investment incentives: Evidence from West Africa, » Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 95, pp. 137-156.

Holden, S. and Yohannes, H., 2002, “Land Redistribution, Tenure Insecurity, and Intensity of Production: A Study of Farm Households in Southern Ethiopia, » Land Economics, Vol. 78 , No. 4, pp. 573- 90.

Jayne, T.S., Yamano, T., Weber, M. T., Tschirley,D., Benfica, R., Chapoto,A. Zulu, B., 2003, “Smallholder income and land distribution in Africa: implications for poverty reduction strategies, » Food Policy, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 253-275.

Kabubo-Mariara, J., 2007, “Land Conservation and Tenure Security in Kenya: Boserup’s Hypothesis Revisited, » Ecological Economics, Vol . 64 , No. 1, pp. 25-35.

Lavigne Delville Ph. (ed.), 1998, What land policies for rural sub-Saharan Africa? Reconciling practices, legitimacy, and legality, Paris, Karthala/French Cooperation.

Lavigne Delville, Ph. and Merlet, M., 2004, “A social contract for land policies,” POUR, No. 184.

Lund, C., 2000, “Land tenure systems in Africa: Challenging basic assumptions,” International Institute for Environment and Development, No. 100.

Migot-Adholla, S.E., Hazell, P., Blarel, B., Place, F., 1991. “Indigenous land right systems in sub-Saharan Africa: a constraint on productivity?, » The World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 155–175.

Ouédraogo, R.S., Sawadogo, J.P., Stamm, V., and Thiombiano, T., “Tenure, agricultural practices and land productivity in Burkina Faso: Some recent results,” Land Use Policy, 1996, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 229-239.

Pinckney, C., Kimuyu, P.K., 1994, “Land tenure reform in East Africa: good, bad or unimportant?, » Journal of African Economies, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 1–28.

Platteau, J.P, “The evolutionary theory of land rights as applied to Sub-Saharan Africa: a critical assessment”, Development and Change, 1996, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 29-86.

Platteau, J.P., 1998, “Land rights, land registration and access to credit,” In Lavigne Delville Ph. (ed.), What land policies in rural Black Africa? Reconciling practices, legitimacy and legality, Paris, Karthala/French Cooperation, pp. 293-301.

Sjaastad, E. and Bromley, D. W., “Indigenous Land Rights in Sub-Saharan Africa: Appropriation, Security and Investment Demand, » World Development, Vol. 25 , No. 4, pp. 549-62.