Forward guidance and devaluation: the Czech central bank’s responses to the crisis

Summary

– The Czech Republic has been in recession for two years, due to the unfavorable economic situation of its trading partners and sluggish domestic demand.

– The Czech government has little room for maneuver between fiscal discipline and supporting consumption.

– Faced with deflationary pressures and having reached the zero lower bond, the Czech Central Bank is forced to resort to less conventional monetary policies, such as forward guidance and devaluation.

– In the Czech context, these policies seem particularly relevant given the country’s dependence on exports.

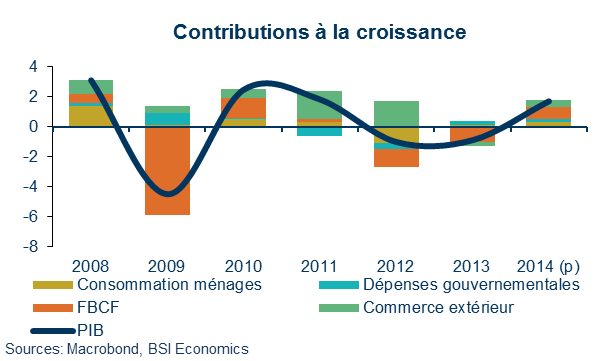

After experiencing a rebound in growth in 2010-2011 thanks to its exports to eurozone countries, notably Germany, its main trading partner, the Czech Republic has fallen back into recession. Victim of the sharp slowdown in growth in the eurozone, it has seen external demand collapse. The resulting slowdown in exports has plunged the country into recession over the past two years.

This was all the more true given the sluggish domestic demand. The gloomy household consumption could be explained by precautionary savings behavior, which would be understandable in a period of crisis and high uncertainty about the future. However, this is not the case: the household savings rate fell sharply between 2012 and 2013, from 10.8% to 9%. The reason for this can be found in wages, which fell in real terms (-1.3%) for the second consecutive year. As a result, household purchasing power is declining. This wage trend can be explained by factors typical of times of crisis: an increase in part-time jobs and the growing importance of the informal sector. However, it is also the result of the rebuilding of corporate margins, which were significantly reduced between 2009 and 2012 in favor of wage increases, which could prove positive in the longer term.

In addition, the Czech economy is facing deflationary pressures. These are the result of weak domestic demand, lower administered prices, such as for electricity, and lower prices for the hydrocarbons that the country imports. At the end of 2013, the consumer price index excluding food had even contracted, raising the specter of deflation.

A government torn between austerity and supporting demand

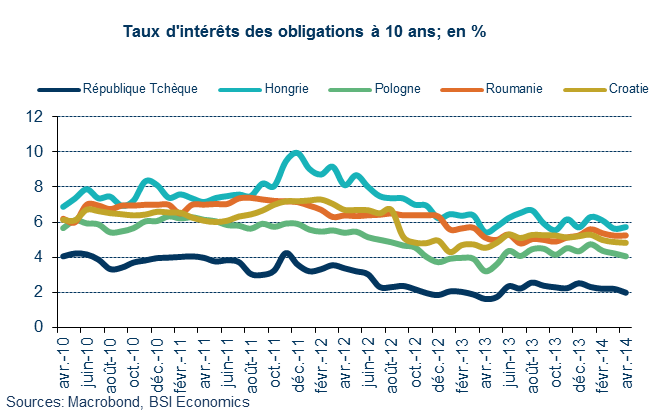

Faced with this particularly difficult economic situation, the Czech government seems torn between fiscal austerity, which allows the country to borrow at low rates (currently 2.01% for 10-year bonds, roughly the same as France and well below other CEECs), and supporting consumption. On the one hand, an increase in VAT from 20% to 21% for the period 2013-2015 and a reduction in social spending have been voted through. On the other hand, a third VAT rate of 10% on books, medicines, and baby food will come into effect in 2015, in addition to the existing reduced VAT rate (15%).

The abolition of regulatory medical fees, tax breaks for employees, large families, and retirees, whose pensions will also be increased, are all measures to support consumption that will come into effect in 2015. However, the government has limited budgetary leeway. The measures mentioned, which are more akin to a helping hand than a comprehensive recovery plan, will not be enough to substantially improve the country’s economic situation.

The role of the Czech National Bank (CNB) is therefore crucial, as it has the second economic policy tool at its disposal: monetary policy. The CNB is independent of the government. Its mandate is to maintain price stability. Inflation must therefore remain around 2%, within a fluctuation band of +/- 1%. Faced with deflationary pressures and with interest rates already particularly low, the CNB is forced to try less conventional monetary policies.

Forward guidance and devaluation: the responses of a central bank with no room for maneuver

The CNB adopted a specific communication strategy, known as « forward guidance, » in January 2008. Initially, this took a Delphic form, more commonly referred to as « soft. » It published its key interest rate forecasts for information purposes, thereby making the future less uncertain for investors. A year later, it decided to also publish forecasts for the exchange rate of the Czech koruna against the euro, becoming the first central bank to do so for a specific currency.

In November 2012, having lowered its key rate to 0.05% and thus reached the « zero lower bond, » the Czech central bank reinforced this communication strategy. Unable to lower its interest rate any further, the question for investors was when it would raise it again. In order to avoid speculation about when it would raise its interest rate, the CNB decided to announce not its own forecasts of potential interest rate movements, but the time frame it would allow itself before raising it. Forward guidance has been used by the Swedish central bank and, above all, the Fed. It helps to limit investor speculation by anchoring their expectations, giving them fixed benchmarks and concrete commitments. However, this expansionary monetary policy has not succeeded in reviving domestic demand, which has remained relatively sluggish.

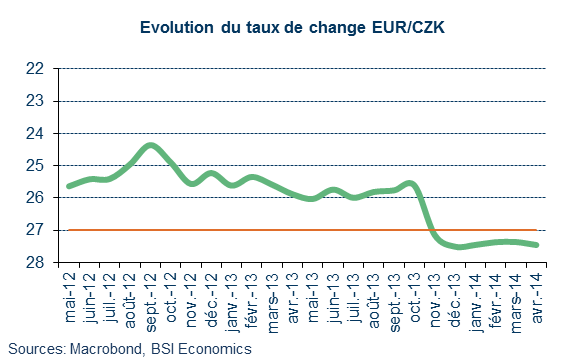

On November 7, 2013, faced with the ineffectiveness of interest rates as a tool for reviving the economy, the central bank decided to use the exchange rate as a monetary policy instrument, devaluing the Czech koruna. The koruna then rose from CZK 25.8 to CZK 27 per euro.

Since then, the central bank has also applied a forward guidance strategy regarding the exchange rate of its currency. It is committed to exercising asymmetric control over the koruna’s exchange rate against the euro. In other words, it will not allow it to appreciate beyond CZK 27 to EUR 1, and will let market mechanisms play out in the event of depreciation. According to announcements by the bank’s board of directors, this commitment will remain in place as long as the risks of inflation falling below the 2% target remain significant. According to the central bank’s estimates, this commitment should not be called into question before early 2015 at the earliest. Since the devaluation, the koruna has remained relatively stable, depreciating slightly against the euro to CZK 27.45.

A relevant solution in the Czech case

By devaluing its currency, the Czech central bank sought to make exporting companies more competitive without further penalizing domestic consumption. Like any economic policy, this option has adverse effects: it leads to inflationary pressures and increases the burden of foreign currency debt. As the currency becomes relatively weaker, foreign goods imported in dollars or euros become more expensive, causing imported inflation. Similarly, debt denominated in dollars or euros automatically becomes more significant. However, the Czech Republic is not exposed to these risks, as it is, on the contrary, facing deflationary pressures and its debt is low (45% of GDP) and mainly denominated in local currency (81%).

This economic policy option therefore seems particularly relevant, especially in an economy where exports account for 77% of GDP. Foreign trade has always been the main driver of growth in the Czech Republic, thanks in particular to the country’s extremely high level of integration into the European production chain.

The automotive industry (8% of GDP and 23% of industrial production) is extremely well represented, due to the relative skill and low cost of labor, which makes it one of the most competitive economies on the continent. Its geographical proximity to Germany makes it a partner of choice for German car manufacturers, such as Volkswagen, which assemble their production there. In this regard, automotive production rebounded significantly in the second half of 2013, growing by 8.7% year-on-year in the third quarter, compared with a 13.2% decline in the first half. The sector benefited particularly from the dynamism of the local company Skoda, owned by the Volkswagen group, which accounted for more than half (57%) of the vehicles assembled in the country in 2013.

However, this policy pursued by the central bank is not without risk. The « exit » strategy will be perilous. The risk of a sharp appreciation of the currency as soon as the forward guidance ends would then negate the positive effects seen so far on export competitiveness and ultimately on growth, if the economy, and in particular private consumption, does not regain its strength by then.

Conclusion

The Czech economy, which has been in recession for two years, is suffering from the difficult economic situation of its neighbors, but also from sluggish domestic demand. The government, forced to exercise a certain degree of fiscal restraint, seems to lack the necessary leeway to provide sufficient support for consumption. Consequently, the Czech central bank’s monetary policy is crucial to reviving economic activity.

Unable to lower its key interest rate, having reached the « zero lower bond, » the CNB has used the full range of monetary policy tools at its disposal. It has implemented a forward guidance strategy, followed by a devaluation of the koruna, which seems particularly relevant in the context of the Czech economy. The use of devaluation seems to make perfect sense in this context of sluggish consumption and deflationary pressures.

The Czech example illustrates how beneficial it can be to have control over one’s own monetary policy, especially in times of crisis. The loss of this tool is one of the main reasons for the gradual disinterest of neighboring non-member countries in the eurozone, beyond the economic slowdown of its leaders. Thus, although it meets all the Maastricht Treaty criteria for joining the euro, the Czech Republic has not set a date for adopting the single currency, on the recommendation of the CNB and the Ministry of Finance. CNB Governor Miroslav Singer recently stated that it should not intervene before 2019 at the earliest. The enthusiasm of the CEECs for the euro when they joined the European Union in 2004, and until the Greek sovereign debt crisis, now seems a distant memory.

Bibliography:

Statistical Office of the Czech Republic

International Monetary Fund (IMF) database