Summary:

– Since 2007, Ecuador has transitioned to a social and solidarity-based economic model in which the well-being of its population is at the heart of economic policy.

– The state acts as a planner, provider of public goods and services, and guarantor of the protection and respect of citizens’ rights, in harmony with nature.

– With the new Montecristi Constitution adopted in 2008, the concept of Buen Vivir or Sumak Kawsai was introduced and became an indicator of social justice. The National Plan for Buen Vivir is a development plan with nine main objectives directly focused on eradicating poverty and inequality in the country.

Ecuador is a country where the fight against poverty and inequality is at the heart of economic and social policies. The eradication of poverty is a major objective of the New Development Plan known as the « Buen Vivir » Plan, established by the New Constitution of Montecristi in 2008.

Poverty is now viewed in a multidimensional way: its monetary aspect is not neglected, but Buen Vivir focuses its efforts on improving citizens’ quality of life, respect for rights, wealth redistribution, social protection, access to education and health services, while respecting different cultures and ethnicities and living in harmony with nature.

Characteristics of the Ecuadorian economy

Ecuador is a dollarized economy (USD) that has experienced sustained economic growth since the 2000s. Between 2000 and 2013, GDP grew by an average of 4.5% per year, and the IMF forecasts growth of around 4.2% in 2014. Compared to Latin America as a whole, Ecuador exceeded the region’s growth in 2013 by 1.7 percentage points.

However, the Ecuadorian economy is primarily characterized by its dependence on exports, which accounted for 31% of GDP in 2013. In addition, 80% of total exports are primary products, 52% of which are oil, making the country highly vulnerable to external shocks, particularly fluctuations in oil prices. Another characteristic is its lack of competitiveness, due in particular to its economy being heavily focused on the production of raw materials and products with low added value on the international market.

The adoption of the dollar as the currency since the 2000s is also a factor that limits state intervention, particularly in terms of monetary and exchange rate policy. In a dollarized monetary system, the Central Bank has a very limited role and therefore cannot devalue the currency or finance the budget deficit by creating inflation, as it cannot issue currency. This loss of monetary sovereignty makes the country more vulnerable to capital movements from foreign economies and dependent on dollar inflows through exports, foreign investment, external debt, and remittances from migrants.

The country stands out for its significant potential in the mining, oil, and gas sectors. Agriculture and fishing are also dynamic sectors: shrimp, tuna, cocoa, flowers, and bananas, of which Ecuador is the world’s leading exporter.

The country is also distinguished by its great natural wealth and exceptional biodiversity: abundant water, fertile soil thanks to its favorable climate, and significant oil reserves. Culturally and ethnically, cultural heterogeneity is reflected in the diversity of its population: according to the latest population census in 2010 (INEC: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos Ecuatoriano), the Ecuadorian population is composed of 72% mestizos, 7.4% montubios[1] , 7.2% Afro-Ecuadorians, 7% indigenous people, and 6% white people. This diversity is also synonymous with different lifestyles and multiple socio-cultural practices.

Historically, Ecuador has suffered from very high levels of poverty and social inequality

The main factors contributing to poverty in Ecuador are: a very low level of education, a low degree of institutionalization, political conflicts, very low economic productivity, a low level of human capital qualifications, and rentier behavior in certain dominant industries (oil, electricity, telecommunications), but poverty in Ecuador is above all a reflection of deep social inequalities among the population.

In the literature, we identify three main periods in Ecuador’s economic history: the oil period (1972-1982), neoliberal adjustment (1983-2007), and the citizen revolution beginning in 2007.

After the oil boom of 1972-1982, Ecuador found itself in a situation of external debt and oil dependency and decided to embark on economic transition and structural adjustments under the provisions of the Washington Consensus. The country’s integration into the global market was based on « traditional » comparative advantages, such as an abundance of low-skilled and cheap labor, but above all the wealth of its natural resources, most of which (oil, metals, minerals, natural gas) are non-renewable and have been exploited in an unsustainable manner. Rentier behavior and the weakening of the state with increasing corruption have prevented the country’s institutional development, as well as the development of basic infrastructure and health, social security, and education services. As a result of these structural failures, the country has seen a worsening of poverty and inequality among its population.

In 1995 , income poverty reached 56% of the total population and 76% in rural areas, with a Gini index[2]stood at 0.57 in the same year, making Ecuador the third most unequal country in Latin America after Brazil and Paraguay (Inter-American Development Bank, 2000).

Between 1999 and 2000, the Asian financial crisis, the devastation of agricultural resources by the El Niño climate phenomenon, the fall in oil prices, and political instability caused a financial crisis in Ecuador that led to the collapse of the banking system and the closure of more than 50% of the country’s financial institutions. As a result of this crisis, urban poverty rose from 36% in 1998 to 65% in 1999. Another consequence was capital flight and mass migration to Europe and neighboring countries, further aggravating Ecuador’s economic situation.

The threat of hyperinflation was very present at that time (the inflation rate in 1999 was 52.2% and reached 96% in 2000. Source: IMF), and faced with a severely depreciated sucre (the former Ecuadorian currency), between 1998 and the early 2000s, its exchange rate rose from around 5,000 sucres per dollar to the official exchange rate of 25,000 sucres per dollar (a depreciation of 477% in the space of 24 months). The country had to adopt the US dollar as the official currency of the economy in January 2000. Faced with a significant drop in real wages and increased political instability at the time of dollarization, poverty in 2000 increased by 13% compared to 1995, reaching 69%.

In 2001, thanks to a recovery in wages and, in particular, remittances from immigrants, the poverty rate fell to 58.3%.

In 2002, this recovery weakened, unemployment rose, and the decline in poverty slowed. Since that year, poverty has continued to decline slowly, mainly due to lower unemployment but also thanks to remittances from immigrants, which have helped maintain household purchasing power and have become the second largest source of foreign currency inflows into the country. Furthermore, this migration is not only composed of the least skilled population, but also includes skilled workers, laborers, and specialized technicians, which has led to a shortage of skilled labor in certain sectors, resulting in higher wages and thus contributing to a reduction in poverty. Between 2003 and 2006, poverty fell by 12% to 37.4% of the population in 2006 (Larrea 2004-2006-2013).

From 2007 onwards ( a period known as the citizen revolution), with the arrival of Rafael Correa in power, the country experienced a degree of political stability. In terms of economic policy, the country moved from a neoliberal model to a social and solidarity-based economic model. The neoliberal model advocated trade liberalization, market deregulation, limited state intervention, and privatization of the public sector. According to various studies, this economic model had harmful consequences on Ecuador’s national industrial fabric, the labor market, the mining and oil sectors, as well as the environment and the population as a whole. The new social and solidarity-based economic model in Ecuador puts human beings, their well-being, and respect for the natural environment first, with the main feature being the role of the state as planner, generator of public goods and services, and guarantor of the protection and respect of rights.

SUMAK KAWSAI: a new indicator of social justice

With the adoption of the New Constitution (Constitution of Montecristi) on September 28, 2008, with 64% of votes in favor at the national level via a referendum, the concept of « BUEN VIVIR » or » SUMAK KAWSAI, « in the indigenous Quechua language, was introduced and is considered an indicator of social justice. « El Buen Vivir, » according to El Atlas de las desigualdades socioeconómicas del Ecuador, is » based on the traditional visions of the indigenous peoples of the Andes and the Amazon, It is a process of participatory improvement of the quality of life, based not only on greater access to goods and services to satisfy basic needs, but also on the consolidation of social cohesion, community values, and the active participation of individuals in decisions to build a future based on equity and respect for diversity. This process is part of a harmonious relationship with nature, where human fulfillment cannot exceed the limits of the ecosystems that support it.

In the 2008 Constitution, development is defined as the dynamic interaction between political, economic, socio-cultural, and environmental systems, and is based on respect for and guarantee of the rights of the population and nature. (Mideros, 2012). Indeed, Ecuador is the first country to have established and recognized the Rights of Nature in its Constitution.[3].

In line with the objective of consolidating a social and solidarity-based economic model in which human beings take precedence over capital and the pursuit of wealth, the National Development Plan, known as the National Plan for Buen Vivir, was established by the New Constitution. (First wave between 2009 and 2013 and a new one between 2013 and 2017). Buen Vivir aims to consolidate the state and popular power, protect and guarantee the rights and duties of Buen Vivir, and bring about economic and productive transformation.

One of the priorities of Buen Vivir is the fight against extreme poverty and inequality in the country, which is why nine of its twelve objectives are closely linked to the national strategy for poverty eradication. Similarly, 53 of the 93 targets to be achieved are focused on reducing poverty in its broadest (multidimensional) definition and inequalities in the country.

To address these significant challenges in terms of poverty reduction and remain in line with the El Buen Vivir plan, the Inter-institutional Committee for Equality and Poverty Eradication was created in May 2013 (Comité Interinstitucional para la Igualdad y la Erradicación de la Pobreza). This committee has implemented a national strategy for poverty eradication (ENEP- Estrategia nacional para la erradicacion de la Pobreza).

This strategy has six main components:

- Quality social services: health, education, inclusive and safe housing.

- Water and sanitation

- Comprehensive protection of citizens throughout their life cycle: Improvement of social protection and security programs, support for people requiring priority care (children up to 3 years of age, people with disabilities, and the elderly), prevention and combating of certain rights violations such as abuse, sexual abuse, begging, and child labor, among others.

- Production and strengthening of the working capacity of the population: access to technical knowledge and technology transfer through vocational training.

- Economic inclusion and social advancement

- Citizen participation and social organization

Poverty is therefore not reduced to a monetary approach; but rather the eradication of poverty from a multidimensional perspective and the creation of a process of upward social mobility that will eliminate or at least significantly reduce the chances of falling back into poverty and prevent the intergenerational transfer of poverty, thereby improving the living conditions of the population.

Ecuador’s progress in reducing poverty

Since 2007, social investment has become one of the mechanisms that guarantees the redistribution of wealth and enables the development of social justice. State social spending has increased considerably. In 2013, 46% of the general state budget was allocated to social spending (health, education, social welfare, housing, etc.). Social spending in 2013 reached 9.6% of GDP, an increase of 5.4 percentage points compared to 2006, when it stood at 4.2% of GDP.

Healthcare spending, for example, rose to 1.9% in 2012 compared to the period 2000-2006, when it accounted for less than 1% of total government spending. In education, government spending rose from 2.3% between 2004-2006 to 4.6% of GDP in 2012. However, despite these advances, social spending is below the Latin American average of 18.6% of GDP.

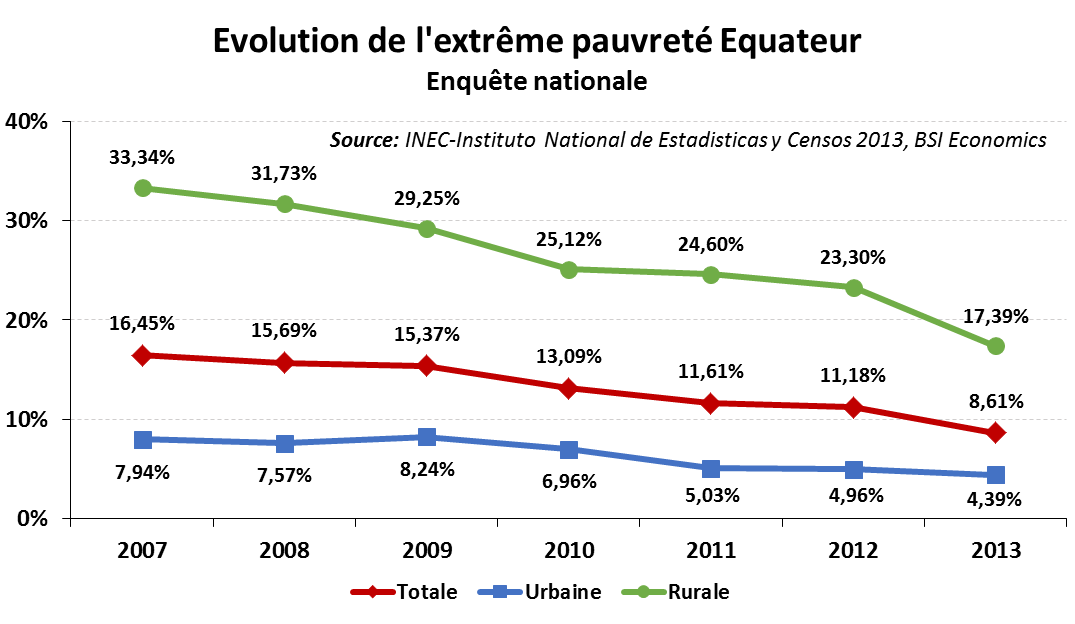

Progress has been made in terms of poverty reduction. In December 2013, the general poverty threshold[4]was set at USD 78.10 per person per month, while the extreme poverty line[5]was USD 44.02 per person per month. Based on these two thresholds, the report on poverty at the end of December 2013 by the Ecuadorian National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC) identifies 25.5% of the population as living in poverty at the national level, a considerable decrease (-11%) compared to 2007, when national income poverty stood at 36.7%. Extreme poverty also decreased (-8%) between 2007 and 2013, falling from 16.5% to 8.61% of the population.

The UNDP’s 2014 Human Development Report ranks Ecuador98th out of 187 countries analyzed, with a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.711, above the global average of 0.702, placing the country in the high human development category. In 2011, Ecuador ranked83rd and was the country that reduced inequality the most between 2007 and 2011 (-8%) in Latin America.

Conclusion

Poverty reduction is a major challenge. The progress made since 2007 is encouraging but remains fragile and insufficient. Inequalities at the national level persist, with the national Gini index in 2013 standing at 0.485, which remains high compared to the regional average. Ethnic inequalities are the most pronounced, with poverty affecting indigenous and Afro-Ecuadorian populations more severely, and geographical inequalities continue to widen between rural and urban areas. Many Ecuadorians still suffer from deprivation in terms of quality housing, education, and security.

It is therefore necessary to increase public efforts to: guarantee access to basic services (water, sanitation) and social security coverage (82% of homes in rural areas do not have a sewage system); provide healthy housing and an adequate environment (15% of households live in overcrowded conditions); generate decent, quality employment (52.5% of the economically active population is underemployed, according to the national employment survey at the end of 2013), and eliminate child labor (according to the first survey on child labor conducted in 2012, 8.6% of children and adolescents between the ages of 5 and 17 work). These areas for improvement are essential in order to continue the fight against multidimensional poverty and provide the population with a sustainable improvement in their quality of life, as desired by the concept of « Buen Vivir. »

Notes:

[1] Montubio:A social ethnic group, descended from mestizos, living on the Ecuadorian coast.

[2]The Gini indexmeasures the degree of inequality in income distribution for a given population. It varies between 0 and 1, with 0 corresponding to perfect equality (everyone has the same income) and 1 to extreme inequality (one person has all the income, while the others have nothing). See further information on the BSI Economics website.

[3]Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador:Nature, or Pachamama, where life occurs, has the right to have its existence, maintenance, and regeneration of its vital cycles, structure, functions, and evolutionary processes fully respected.

[4]General poverty threshold:a person lives in general poverty if they do not have sufficient income to meet their basic non-food needs (clothing, energy, housing, etc.), as well as food.

[5]Extreme poverty threshold: a person lives in extreme poverty if they do not have sufficient income to meet their basic food needs, defined on the basis of minimum calorie requirements.

References

– » Ecuador: Definition and multidimensional measurement of poverty, 2006-2010, » Revista Cepal No. 108, Andres Mideros, 2012.

– » Crisis, dollarization, and poverty in Ecuador, » Carlos Larrea Maldonado, 2012.

– » Eradicating poverty: an urgent goal, » Revista Ecuador Economico No. 12, Publication of the Coordinating Ministry of Economic Policy, November 2013.

– Macroeconomic statistics, Central Bank of Ecuador, May 2014

– » Human Development Report, » United Nations Development Program, 2000/2011/2013.

– « National Development Plan/National Plan for Good Living 2013-2017, « National Secretariat for Planning and Development (Senplades), 2013

– » Ecuador: Strategy for the Eradication of Poverty, « National Secretariat for Planning and Development (Senplades), July 2013

– » Atlas of Socioeconomic Inequalities in Ecuador – Social Development, Inequality, and Poverty, « National Secretariat for Planning and Development (Senplades), Carlos Larrea Maldonado, 2013

– » National Survey on Employment, Unemployment, and Underemployment – Poverty Indicators, « National Institute of Statistics and Census, December 2013.

– » First National Survey on Child Labor, « National Institute of Statistics and Census, December 2012

– Poverty in the Citizen Revolution or Poverty of Revolution?, Juan Ponce and Alberto Acosta, November 2010

– » The Dollarization of Ecuador, One Year Later, « Mathieu Ares, Research Group on Continental Integration, December 2001