DISCLAIMER: The person is speaking in a personal capacity and does not represent the institution that employs them.

Summary:

– Macroprudential policy aims to prevent large-scale disruption to the provision of financial services, which would have serious consequences for the real economy.

– Macroprudential policy is not neutral with respect to other economic policies, which can create interference or blockages between different authorities.

– Implementing effective macroprudential policy is inherently difficult. On the one hand, implementing macroprudential policy measures is politically sensitive, which can lead to inaction. On the other hand, after a series of serious crises, the macroprudential regulator may be biased toward excessive interventionism.

The vast undertaking of reforming banking and financial supervision aims to supplement traditional microprudential regulation, which focuses on individual risks, with macroprudential analysis that takes into account risks as a whole, i.e., focusing on systemic risk (an article by the same author is available on the BSI Economics website). Macroprudential policy can thus be defined as having the objective of « limiting systemic risk, i.e., the risk of a large-scale disruption in the provision of financial services, which would have serious consequences for the real economy » (CGFS, 2012); in other words, to avoid, as far as possible, crises that jeopardize the stability of the financial system.

The objectives of macroprudential policy

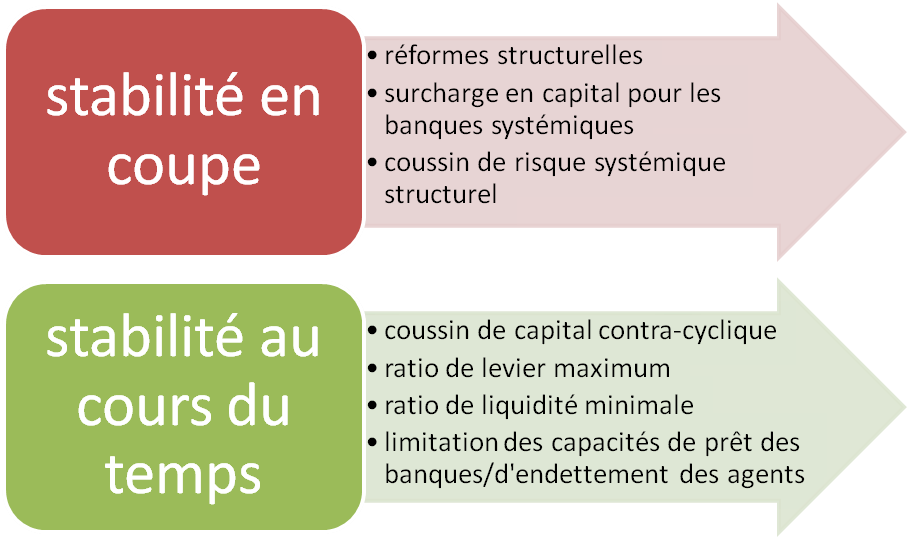

Two central objectives of macroprudential policy relate to the two main dimensions of systemic risk, namely the cross-sectional dimension and the temporal dimension.

On the one hand, macroprudential policy aims to strengthen the resilience of the financial system, i.e., « its ability to absorb economic and financial shocks while avoiding major repercussions on the real economy »(Bennani et al., 2013). Thus, the risk of collective or « chain » defaults, characteristic of a contagion phenomenon, must be internalized by financial institutions; such a domino effect results either from excessive interconnection and opacity, or from common exposures to certain extreme risks.

On the other hand, macroprudential policy aims to limit the inherent procyclicality of the financial system, i.e., created in and by the financial system. Procyclicality can thus be understood as the mechanism by which the financial system amplifies economic cycles and variations in the real economy (Borio et al., 2001). Either risk-taking is too high in expansionary phases, due to excessive optimism known as the « paradox of tranquility » (Minsky, 1986). Or risk-taking is too low in times of crisis due to excessive risk aversion, which can be reinforced by information asymmetries and regulatory requirements.

In practice, an indicative list of more restrictive intermediate objectives has been drawn up by the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB, 2013) with the aim of ensuring better risk identification and analysis of the effectiveness of macroprudential policy. These more operational objectives would be:

- Limiting excessive credit and leverage growth, particularly through risk underestimation;

- Limiting maturity mismatches between assets and liabilities to avoid liquidity runs/forced sales following a loss of confidence or a change in expectations;

- Limiting the concentration of direct or indirect risks: the default of a counterparty in a risk hedging contract can generate contagion via the loss of insurance on certain assets (e.g., AIG [1]);

- Limit the systemic consequences of moral hazard, i.e., the propensity of large financial institutions, implicitly insured by the government, to take greater risks.

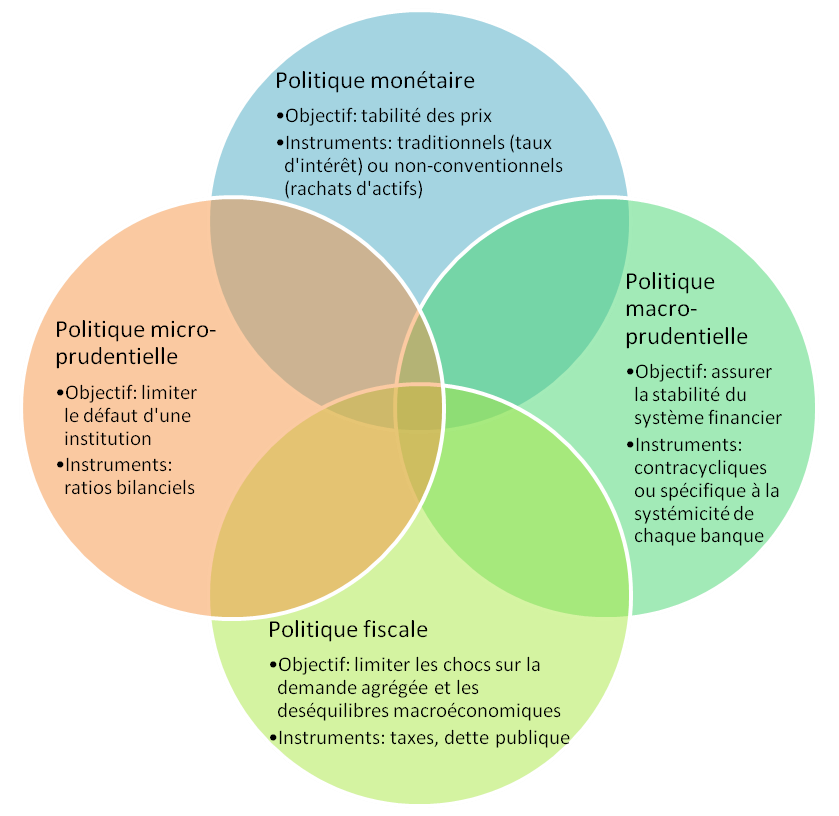

Complex integration with other policies

Macroprudential policy is not neutral with regard to other economic policies, which can create complementarities or blockages between different authorities.

- Macroprudential policy is closely linked to fiscal policy. (i) On the one hand, limiting the supply of credit may run counter to redistributive or expansionary fiscal policies; for example, limiting households’ borrowing capacity to purchase real estate may run counter to tax exemption policies that promote home ownership. (ii) On the other hand, excessive public sector debt can increase the vulnerability of the banking system, which is more exposed to sovereign risk (as in Greece). (iii) Finally, the implicit guarantees granted by the state to large banks (« too big to fail ») may limit the effectiveness of macroprudential policy by increasing incentives for systemic risk-taking.

- Macroprudential policy is also closely linked to monetary policy(Beau et al. 2012), with the two generally complementing each other: by limiting the spread of shocks to asset prices or credit supply, macroprudential policy can strengthen the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. However, the two do not necessarily go hand in hand: in periods of controlled inflation, the emergence of a bubble (as in the US real estate market) cannot be prevented by monetary policy. Furthermore, the balance sheets of over-indebted institutions can be strengthened by eroding the real value of liabilities or by supporting asset prices, which can lead to a return of inflation.

- Finally, macroprudential policy is closely linked to microprudential policy, with which it shares certain tools (capital or liquidity ratios). However, the objectives are different: during a banking crisis, it may be in the interest of the microprudential authority to tighten the requirements for certain banks identified as being at risk. But this can amplify contagion by imposing a faster and simultaneous adjustment of the banking sector, which would ultimately tighten credit supply. A macroprudential authority will therefore favor relaxing regulatory constraints to avoid an overly abrupt adjustment in the short term. By analogy with the world of finance, the macroprudential authority seeks to maximize the return on the securities portfolio (the financial system), while the microprudential approach gives equal and separate weight to the performance of each security in the portfolio (each financial institution).

Macroprudential policy tools

In order to achieve all these objectives, a number of instruments, particularly those focused on the banking sector [2], can be used. Some have been introduced into European law via the CRR/CRD IV regulations, while others are still under discussion for future implementation. For more details, see Bennani et al. (2013).

A first set of instruments aims to strengthen the resilience of the financial system and focuses on the cross-sectional dimension of macroprudential policy.

- Measures modifying the structure of the banking system to preserve traditional retail/deposit activities fromriskier market activities by grouping them into more or less separate entities, each of which must individually satisfy prudential regulatory constraints. These measures have been implemented through the Volcker reforms in the US, the Vickers reforms in the UK, and the Liikanen project in Europe, although their implementation falls far short of the initial ambitions.

- Strengthened capital requirements for large international banks identified as systemic(known as « G-SIBs, » effective January 2016). BNP should therefore hold an additional 2 percentage points of capital (above the regulatory minimum of 8% of risk-weighted assets), compared with 1.5 points for Crédit Agricole and 1 point for BPCE and Société Générale (FSB, 2013).

- A systemic risk buffer, i.e., a strengthening of capital requirements to limitnon-cyclicalstructural, accounting, or regulatory risksspecific to certain banking sectors, with a maximum of an additional 5 percentage points.

A second set of macroprudential measures focuses on the inherent instability of the financial system, i.e., the temporal dimension of macroprudential policy.

- The countercyclical capital buffer, which aims to increase the capital of banking institutions during periods of growth in order to limit excessive credit supply, and converselyto reduce regulatory capital requirements in the event of a crisis in order to increase the supply of loans and thus facilitate access to credit (operational since 2014 in France and Europe);

- The leverage ratio ( the precise definitionof which has not yet been finalized), which should limit the possibilities for financing per unit of capital. The advantage lies in its simplicity, which minimizes potential errors in risk estimation or incentives for regulatory arbitrage and financial innovation. The risk weights used to calculate regulatory capital requirements are imposed by the regulator (for example, sovereign debt has a risk weight of zero), but most banks are able to choose the risk category that best applies to each of their assets (internal IRB model).

- An increase in the proportion of liquid assets on banks’ balance sheets so that they can cope with a month ofdeposit withdrawals, margin calls on derivatives, or a drying up of short-term funding sources. The advantage of such a « liquidity coverage » ratio, which is still in the works, is that it allows sufficient time for the competent authorities to take the most appropriate measures.

- A limitation on banks’ lending capacity/agents’ debt capacity so that , on the one hand, banks avoid excessive use of short-term financing and, on the other hand, market bubbles, particularly in real estate, are avoided. However, these tools, which are used in Southeast Asia (Hong Kong and South Korea, for example), are not currently provided for in international agreements and are therefore left to the discretion of national authorities.

In conclusion, implementing an effective macroprudential policy is inherently difficult. On the one hand, macroprudential policy measures can be politically sensitive, which can lead to inaction. Indeed, this amounts to reducing economic growth in the short term in order to avoid the possibility of a bubble bursting a few years later. On the other hand, after a series of serious crises, macroprudential regulators may be biased toward excessive interventionism (IMF, 2012).

Before memories of the crisis fade, it is necessary to clarify the legislative arsenal (notably through the French banking law of July 2013) and to strengthen the tools available, even if not all instruments will necessarily be operational immediately. In fact, it may even be preferable not to activate all the new provisions too abruptly, given the scale of the reforms underway, beyond the banking sector alone, which are not necessarily coordinated with each other.

Notes

[1] The American insurance giant AIG had significant positions in credit default swap insurance contracts: in exchange for an insurance premium, such contracts guarantee the value of an asset if it falls below a certain threshold. Such contracts are typically over-the-counter, and AIG had become one of the most important players in this market. Between January 2007 and September 2008, AIG’s CDS division recorded losses of $32.4 billion: given the deterioration of the economy, AIG was forced to honor its insurance contracts and reimburse its customers. AIG’s bankruptcy would have left all its other counterparties unprotected against the losses that were looming in 2008. As AIG could not default, the insurer was bailed out by the US Treasury. See Sjostrom, W. (2009). « The AIG Bailout, » Washington and Lee Law Review, vol. 66, pp. 943

[2] Other macroprudential regulations are in the pipeline, particularly concerning financial markets, the use of central counterparties for derivatives management, the extension of rules applicable to leveraged funds and the shadow banking sector, and the regulation of the insurance sector, which has been less regulated until now.

References

For further details, see mainly sections 2 and 4 of:

– Bennani, T., Després, M., Dujardin, M., Duprey, T., and Kelber, A. (2013). , forthcoming Banque de France Occasional paper.

– Bank of International Settlements (2011). Central Bank Governance and financial stability, Report by a Study Group.

– Beau, D., Clerc, L., Mojon, B. (2012). Macro-prudential policy and the conduct of monetary policy, Banque de France Working Paper No. 390.

– Borio, C., Furfine, C.H., Lowe, P. (2001). Pro-cyclicality of the financial system and financial stability: Issues and policy options. BIS Paper No. 1.

– Committee on the Global Financial System (2012). Operationalizing the selection and application of macroprudential instruments. CGFS Publications No. 48.

– Duprey, T. (2013). In search of a definition of systemic risk, BSi-Economics.

– European Systemic Risk Board (2013). Recommendation on the intermediate objectives and instruments of macro-prudential policy, April 4, 2013 (ESRB/2013/1).

– International Monetary Fund (2012). The interaction of monetary policy and macroprudential policies—background paper.

– Minsky, H. (1986). Stabilizing an Unstable Economy, Yale University Press.