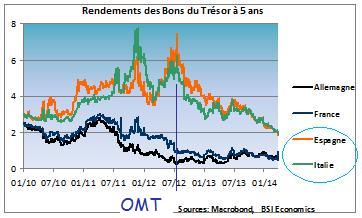

In the news: despite not having been activated, the ECB’s announcement of OMT (Outright Monetary Transactions) in July 2012 has, according to many observers, helped to lower the interest rates at which peripheral countries borrow. Some have referred to this effect as the « Draghi put » (see our references). What does this mean?

The Greenspan put referred to the implicit assurance of « no losses » enjoyed by US financial markets when Alan Greenspan was chairman of the Fed (1987-2006). We have already discussed this term on our website. Given the Fed’s response under Alan Greenspan’s leadership during the 1987 stock market crash, and its similar responses during the stock market crashes of the 1990s (particularly in 1997-98), the idea that the Fed would intervene in the event of a sudden and sharp fall in prices became popular, giving rise to the expression « Greenspan put. » Why « put »? Central bank intervention in the event of a fall in stock prices through a more accommodative monetary policy theoretically has a positive impact on the stock markets and therefore on asset prices, thus avoiding losses that would have occurred if the Fed had maintained the status quo. This « insurance against losses, « or rather limited losses to be more precise, can be likened to the definition of a « put » option in finance, which is an option that provides its holder with insurance against a decline in the price of an asset. The « put » metaphor therefore comes from this similarity with a put option in terms of the triggering of the insurance and the consequences in terms of losses.

So why talk about the « Draghi put »? Quite simply to describe the fact that investors expect the central bank to react in the event of a fall in prices, as in the case of Alan Greenspan. With a few differences.

We are not talking here about share prices, but bond prices, and particularly the prices of bonds from peripheral countries. In other words, we expect the central bank to intervene to support the prices of bonds from peripheral countries (with the aim of keeping interest rates at reasonable levels).

This expectation is not based on Mario Draghi’s past actions, as was the case with Alan Greenspan, but on his words. The OMT has not been activated, but investors expect it to be triggered in the event of a sustained bond crisis in peripheral countries. This OMT, coupled with Mario Draghi’s repeated statements that the euro is « irreversible, » has led markets to expect the ECB to intervene in the event of a sharp rise in interest rates for peripheral countries. This OMT can be thought of as insurance: if prices plummet, the markets anticipate that the central bank will react by buying assets from peripheral countries on a large scale, which will support asset prices. In other words, it is insurance against a fall in prices. A « Draghi put, » in other words.

Graph: The announcement of the OMT in July 2012 benefited peripheral countries.

This « Draghi put » allows peripheral countries to benefit from « reasonable » interest rates. But it is based primarily on one element: the OMT. An element whose legitimacy has been questioned by some in the German Constitutional Court, which itself recently decided to refer this question of legitimacy to the Court of Justice of the European Union (ECJ). If the ECJ rules in favor of the OMT’s opponents, it would spell the end of the « Draghi put » and a rise in interest rates for peripheral countries, which could be very destabilizing for them.

Julien Pinter

Twitter: ![]() JulienPinter_BSIeco

JulienPinter_BSIeco

Notes

[1] Unless we consider the second LTRO as an intervention that helped to boost asset prices, thereby acting as ex post insurance. This seems less obvious than in the case of a rate cut motivated by stock market considerations (similar to the Greenspan case) or in the case of large-scale asset purchases.

For further reading:

« German constitutional judges offer respite to the ECB » (Le Monde, February 8, 2014)