Unobserved heterogeneity has long been, and sometimes continues to be, one of the central problems of econometrics, and therefore, by extension, of any economic theory based on statistical work. For certain economic theories (see below), issues of unobserved heterogeneity have clearly been the number one problem highlighted by their opponents or by the most skeptical, thus fueling numerous research articles. What are we talking about?

Intuition

It often happens, during a coffee break discussion, for example, or even during televised debates, to hear assertions presented in a peremptory manner, supported by arguments such as « look, since we had such and such a thing x, such and such a thing y has happened. » The speaker often argues that there is a causal link: event y is due to event x. For example, poor economic performance in a certain country (y) is said to be due to economic reforms undertaken at the same time (x), or to the arrival of a new party in government. A graph showing that the two events are correlated will then provide seemingly « convincing » evidence.

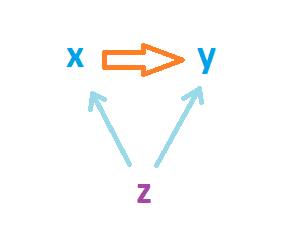

But only on the surface. Let’s start with a very simple example, which has the disadvantage of being political but the advantage of being very telling. In 2007, Nicolas Sarkozy came to power in France. In 2008 and 2009, GDP fell sharply. So there is a correlation… Is the fall in GDP (y) due to Nicolas Sarkozy coming to power in France in 2007 (x)? A hermit emerging from his habitat in 2009 would be tempted to draw this conclusion upon learning the facts. However , he would be overlooking a fundamental factor z that he did not observe: the onset of the global crisis following the subprime crisis. While some may argue that the new president bore some responsibility (that is not the issue here), most of the decline in our GDP during this period can be attributed to this single third factor (z): the global economic crisis. Once we have this factor z in mind and it is no longer « unobserved, » we can see more clearly the main reasons for the fall in GDP in France in 2008, and thus avoid jumping to conclusions.

Generalization to economic studies

How can we generalize this very simple (even simplistic) example in the context of economic studies? Let’s suppose we are interested in the effects of central bank independence (x) on a country’s inflation (y). The generally accepted idea on this subject is that the more independent a central bank is in a country (x), the lower the inflation (y) will be. Why? Because in theory, the more independent a central bank is, the less receptive it will be to the wishes of the government [0]. If the government, as is often the case in the run-up to elections, wants the central bank to set aside its inflation target in order to stimulate short-term demand through expansionary monetary policy, a legally independent central bank will have more means to say no than a central bank that is clearly under the control of the state. To test this theory, economists have used econometrics.

The first empirical studies on this subject are what are known as cross-sectional studies: for each country, data is compiled by taking the averages of inflation and the level of central bank independence over several years[1], and then testing whether variations in the level of independence between countries are correlated with variations in inflation between countries. These early studies clearly show a negative correlation between central bank independence and inflation over long periods (see Alesina and Summers (1993), for example).

However, some researchers have pointed out the existence of a possible problem of unobserved heterogeneity in this method. This link between independence and inflation may simply be due to a third factor z: the culture and traditions of the country. For example, in a country such as Germany, which experienced hyperinflation in the 1920s, the population will attach particular importance to inflation, leading the public authorities to clearly separate the central bank from the government. In a country such as the United States, which has not had this problem, the population will attach less importance to inflation and the public authorities will have less incentive to separate the central bank from the government. The data will therefore show inflation (y) varying at the same time as the level of independence of the central bank (x), even though the initial reason is not the level of independence but the country’s culture with regard to inflation (z)! In other words, the interests of economic agents rather than economic institutions.

The problem of unobserved heterogeneity dominated (and in some cases continues to dominate) much of the independence/inflation debate in the 1990s (see in particular the work of Posen referenced below and Hayo (1998)).

Thus, when assuming the existence of a relationship between two variables x and y, it is always necessary to check that the relationship is not due to a third factor z that is strongly correlated with x. If this is the case, we are in fact faced with a problem of unobserved heterogeneity. This problem can be solved by economists simply by adding a control variable to their model (see the explanation here). Of course, this is only possible when it is possible to find a variable corresponding to the unobserved factor z, which can sometimes be difficult (what data should be used for culture in our previous example?) and often remains the main problem in economic studies.

Julien P.

Notes

[0] Other arguments exist, but we are sticking to the main one here for the sake of simplicity. See our references for more information.

[1]In general, independence does not change or changes very little over time, which limits the use of temporal variations and justifies the use of an average.

Additional references

Very informative video from HEC Lausanne on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dLuTjoYmfXs

Alesina, Alberto & Summers, Lawrence H, 1993. « Central Bank Independence and Macroeconomic Performance: Some Comparative Evidence, » Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Blackwell Publishing, vol. 25(2), pages 151-62, May.

Hayo, B. 1998, Inflation Culture, Central Bank Independence and Price Stability, European Journal of Political Economy, 14, 241-263.

Posen, A., 1993, Why Central Bank Independence Does Not Cause Low Inflation: There Is No Institutional Fix for Politics, in: O’Brien, R. (ed.), Finance and the International Economy 7 (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Posen, A.S., 1995, Declarations Are Not Enough: Financial Sector Sources of Central Bank Independence, in: Bernanke, B. and J. Rotemberg (eds.), NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1995 (Cambridge MA: MIT Press)

Posen, A.S., 1998, Central Bank Independence and Disinflationary Credibility: A Missing Link?, Oxford Economic Papers, 50, 335-359.