« Debt monetization, » an operation that consists of converting a government’s debt into currency (more on this below), is a concept that appeared very often in economic debates in the 20th century. At the time, monetization was viewed by economists such as Friedman as an economic operation carried out by irresponsible governments, with harmful economic consequences. Today, the specific nature of central bank tools means that current « monetization » bears little resemblance to « 20th-century monetization. » The reason for this is the remuneration of bank reserves, which makes money « profitable » for the state. This change has led to a modified interpretation of the term « monetization, » to which economists and observers have yet to adapt.

Monetization:

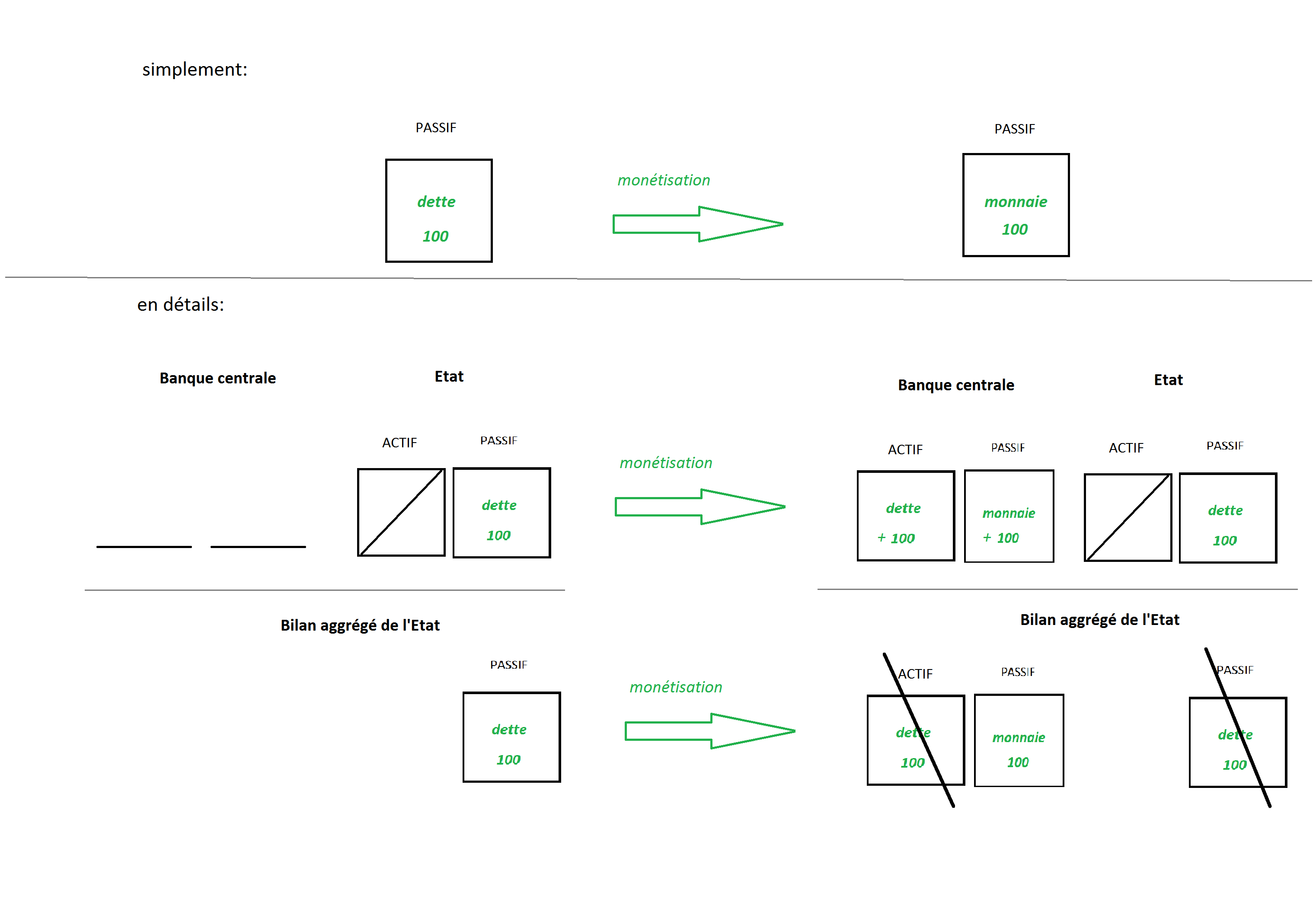

Monetizing debt means « turning debt into money. » In practical terms, government debttoday takes the form of bonds. Monetization consists of converting these bonds into money. The way to achieve this is simple: the central bank in the state in question buys the state’s debt. Ultimately, the operation means that the state’s debt (at the aggregate level) is no longer a security on which it owes interest, but money. [1]

The monetization operation in practice, aggregate government balance sheet:

Monetization today vs. monetization in the 20th century:

The fundamental difference between monetization today and monetization in the 20th century stems from the remuneration of reserves, which has become widespread in the central banks of advanced countries in recent years. When the central bank buys government debt, it replaces it with a special form of money: reserves (or electronic money). The central bank will buy a government debt security from a bank, for example, and credit that bank’s account. This effectively results in monetization: government debt has been replaced by money (reserves), as can be seen in the chart above.

In today’s world, where reserves earn interest, « monetization » has little impact on the government’s financial situation. This is because, due to the very nature of monetary policy, the rate at which the government borrows is generally closely linked to the rate of return on reserves. To simplify matters, let us assume that these two rates are equal [2]. In this case, the government replaces debt securities on which it pays X% with currency on which it pays interest equal to X%: the financial gain is zero. In the 20th century, when excess reserves paid no interest, the situation was different. The government exchanged debt securities on which it paid X% for currency on which it paid no interest: monetization was good for the government’s finances! In addition, monetization had inflationary consequences, which are now effectively limited by the remuneration of excess reserves (which set a floor on short-term interest rates).

Ultimately, debt monetization today can no longer be considered the economic sacrilege it was in the 20th century. In a world where the central bank pays interest on reserves at levels close to the key interest rate, the financial gains for the state are very small and the inflationary consequences limited. This is nothing like the monetization of the past, when the state could rely on monetization to significantly reduce its debt burden while generating inflation.

Julien Pinter

[1] In detail: the central bank issues currency to finance the purchase of government debt. The government pays interest to the central bank, but the latter returns it at the end of the year through profit distribution. The government’s debt has therefore ultimately been exchanged for currency, and the cost of this debt depends on the « cost » of the currency.

[2] In reality, the rate of return on reserves must be adjusted to take into account the natural difference in maturity between reserves and government bonds. For example, the implicit one-year rate of return on reserves (current rate and forward rate) must be compared with the one-year OAT rate to produce a relevant comparison over a one-year maturity.