Abstract :

– Much attention is focused on when the Fed will tighten its monetary policy.

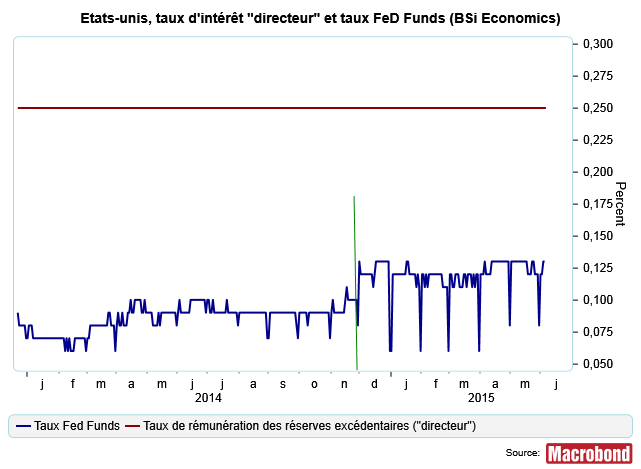

– It is often forgotten that the Fed has already begun to raise rates significantly since last December: the Fed Funds rate, targeted by the Fed, has since doubled compared to its average level in 2014.

– To do this, the Fed uses two specific tools (reverse repos and term deposits).

– In its latest minutes, the Fed acknowledged that it is conducting « experiments » to provide a « soft » floor for the Fed Funds rate.

Since the end of the Fed’s Quantitative Easing program (« QE, » large-scale asset purchases), markets and commentators have focused on what is now the main tool of U.S. monetary policy: the Fed’s key interest rate, which has been set at 0.25% for six years now. By setting its key interest rate at a certain level, the Fed seeks to influence the main interbank market rate (the rate at which banks lend to each other on a day-to-day basis, known as the Fed Funds rate ), a key rate since it then influences all the rates that are important for the economy.

While speculation is rife about when the Fed will raise its key interest rate, it seems to be forgotten that the Fed has already been acting on the interbank market since December 2014 by raising rates. The Fed Funds rate peaked last December and has remained at that level ever since (doubling its average level for 2014), a move that is the result of Fed actions that are often overlooked.

Excess supply on the interbank market

Since the start of QE3 in September 2012, the Fed has purchased an average of nearly $60 billion in securities per month, equivalent to nearly $1.5 trillion. Since each of these securities purchases automatically results in an increase in liquidity in banks’ current accounts, banks have found themselves with enormous amounts of liquidity. As a result, the amounts in banks’ current accounts at their US central bank totaled $2.629 trillion last October after the end of QE.[1], compared with only $33 billion in the « normal » context of early 2008.

With such a high level of liquidity, the interbank market is theoretically out of balance: the supply of liquidity is abundant and the demand for liquidity is scarce. Each bank has a comfortable level of liquidity and therefore, in theory, wants to lend this liquidity to other banks. One of the basic principles of economics tells us that in this context, where supply far exceeds demand, the price of liquidity (the Fed Funds rate) should be very low, or even zero. If the Fed wishes to raise the Fed Funds rate, it must therefore use tools capable of rebalancing the interbank market. One such tool is its key interest rate, which since 2008 has been the rate at which it remunerates banks’ excess liquidity (known as the interest rate on excess reserves).

The key interest rate is insufficient to raise rates

By paying interest on banks’ excess liquidity (i.e., liquidity held in addition to that held to meet regulatory requirements), the Fed encourages banks not to lend their liquidity at rates lower than the rate at which it pays them on their current accounts. A bank is not going to lend overnight to another bank at a rate of 0.24%, for example, when it can place its cash with the central bank at a rate of 0.25% for the same maturity. In theory, therefore, the remuneration of excess reserves makes it possible to set a floor rate for the Fed Funds rate. However, when we look at the figures, we see that the Fed Funds rate has been consistently below the rate of remuneration for excess reserves for several months.

If the mechanism described above does not seem to work in practice for the Fed, it is simply because not all banks have access to the remuneration offered by the central bank. This is particularly the case for the famous government-sponsored enterprises, state-linked banking institutions (Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Home Loan Banks), for which the Fed does not pay interest on excess liquidity, and which are therefore in practice encouraged to lend their liquidity at a rate above 0 only, rather than at a rate above the interest rate on excess reserves. In this context, the Fed must take other measures to rebalance the interbank market and ensure effective control over the Fed Funds rate. It has been doing so step by step for several months, using methods that have become increasingly important in recent times.

Two complementary tools of growing importance

To regain control over the Fed Funds rate, the Fed is acting on the supply of liquidity through another channel: it is directly withdrawing excess liquidity from banks in the system. In doing so, it is making liquidity scarcer on the interbank market and therefore, in theory, more expensive; in other words, it is allowing the Fed Funds rate to rise closer to the level of the key interest rate. In the minutes of its December 2014 meeting, the Fed initially referred to these as simple « tests, » but has since referred to them as « continued tests » (see April minutes). The latest minutes explicitly show that, in doing so, the Fed is seeking to set a floor on the Fed Funds rate (« soft floor, » see April minutes). It is using two tools to achieve this: reverse repos and term deposit facilities.

Reverse repos are temporary lending operations: the Fed lends securities to banks in exchange for their cash for a period ranging from one day to nearly one month. Importantly, these operations are available to a wide range of banking institutions, including the famous government-sponsored enterprises. Term deposit facilities are investment products offered by the central bank to commercial banks: they can deposit their cash with the central bank for a period of one week in exchange for a certain return. By offering increasingly attractive rates for these transactions, the Fed has withdrawn record amounts of cash from the interbank market. By mid-December, more than $600 billion in cash had been collected through the Fed’s two tools. As a result, Fed Funds rates logically rose, reaching an average of 0.12% in December 2014, a level they had never reached on a single day in 2014. They have since remained at similar levels on average.[2], thanks in particular to reverse repos conducted for a wide range of maturities with the GSEs.

Conclusion

So, whether this is a very prolonged experiment or the beginning of a change of course in monetary policy, the facts speak for themselves: the implicit target for the Fed Funds rate has been close to 0.25% for a long time now. The Fed’s monetary policy tightening has, in fact, already begun.

Julien P.

References:

– Minutes of the FeD, December 16-17, see reference to « tests of supplementary normalization tools, »second paragraph on page 2 http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcminutes20141217.pdf

– FeD minutes, March 17-18,1st paragraph on page 2 http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcminutes20150318.pdf

– Minutes of the FeD, April 28-29,1st paragraph on page 2: http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcminutes20150429.pdf

– « Fed will continue reverse repo through January 2016, » Wall Street Journal (link here)

Further reading:

– » The mechanics of a graceful exit: Interest on reserves and segmentation in the federal funds market, » Journal of Monetary Economics, 2011 (article explaining the key role of GSEs in controlling Fed Funds and why the arbitrage hypothesis is not sufficient).

– « The Fed exit monitor V.2, » Peter Stella, March 2015, link here(very informative article on the technical details of Fed operations)

“The Daily Market for Federal Funds,” James Hamilton, Journal of Political Economy, 1996

Notes: