Summary : The Blue Planet Paradox

- An « imminent risk of a global water crisis » was raised by UNESCO and the UN at the Water Summit held in April 2023.

- Global warming, and with it the increase in the frequency and severity of extreme events, including drought and precipitation, raises questions of vulnerability, adaptation, and resilience at various levels, from businesses to states.

- The dependence of economic sectors on water varies according to their withdrawal, consumption, and use. Among the sectors most at risk are agriculture, agri-food, the chemical industry, manufacturing, the energy industry, and mining.

- Given the interdependence between industries, an analysis of the sectoral impacts of water management issues must be carried out using a value chain approach.

- Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM), corresponding to the international organization Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM), is a benchmark method for sustainable water use which, combined with international cooperation in resource management, represents a solution to the problems of water scarcity.

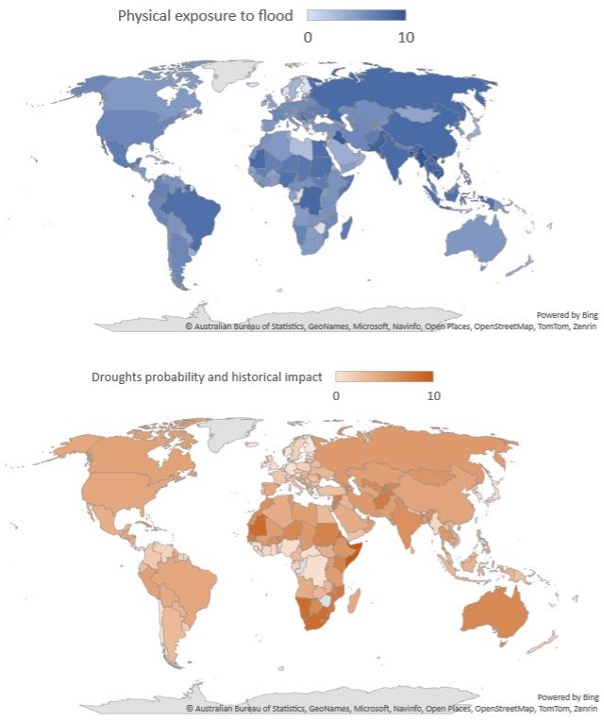

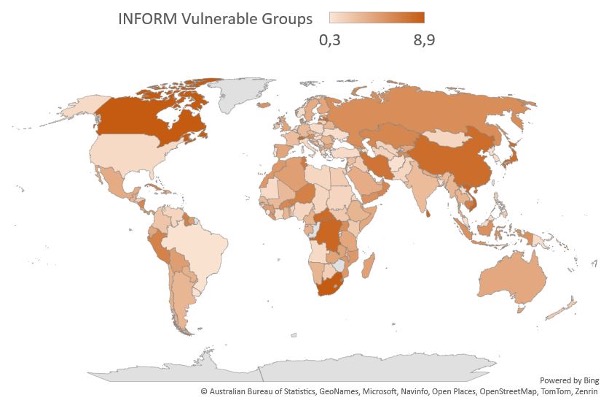

- A simplified view might suggest that developing countries are most exposed to water risks, but the geographical dimension of these issues, the interdependence between countries, and uneven demographic trends around the world make it difficult to estimate exposure to these problems.

In recent years, many leading organizations (including the United Nations (UN) and the World Economic Forum (WEF)) have frequently mentioned the risks associated with water scarcity, the impact of which could prove decisive by 2030 (WEF, 2022). Indeed, growing consumption of goods and services and environmental degradation (industrial waste, chemical pollution, wastewater) are leading to a scarcity of resources, with significant regional disparities. Furthermore, increasing global warming is correlated with an acceleration in the frequency and severity of destructive water-related events.

Even though the world has been shaped around drinking water, the development of efficient means of transport and agricultural techniques has led us to believe that its use is infinite, thus distancing us from the considerable challenges posed by water management in our daily lives.

It is therefore necessary to combine environmental science and economics in order to understand the real challenges surrounding water resource management.

1.Drought, cyclones, and floods: risks that raise the question of adaptation

Extreme water-related events

Nine out of ten natural disasters are water-related (Eau, 2022). Indeed, the scientific community has highlighted the increase in global temperatures, the greater frequency of extreme precipitation events, and the increased severity of these phenomena (Easterling, et al., 2002).

Before any analysis, a distinction must be made: so-called « continuous » climate events (such as precipitation) are predictable using climate models, unlike one-off events (such as droughts), whose statistical distribution is « discontinuous. » This distinction suggests that the ability to understand and anticipate future drought events, whether in historically at-risk regions or in regions that have never experienced such events in the past, is limited.

What we know for certain is that droughts, floods, heat waves, and precipitation are linked to certain physical parameters such as water temperature and precipitation intensity. Put simply, if we use any method to increase the water temperature in a region, reduce the flow of a river, or use groundwater, we know that we are altering the balance of a natural ecosystem, but we do not systematically know how a series of combined events will change the future of this resource.

The issue of groundwater

What we refer to as adaptation in this note focuses on adjusting to new demographic and climatic conditions, while resilience focuses on the ability to cope with disruptions and recover quickly from impacts. Both concepts are crucial to strengthening the capacity of societies and ecosystems to cope with the challenges posed by change.

We could divide water sources into two categories: surface water and groundwater, although the two are closely connected.

Only 3% of the water on the planet is fresh water, and 30% of this water comes from groundwater (Fresh water: its formation, reservoirs, and available resources, 2021). The use of groundwater as a water reservoir is a strategic issue in a world increasingly exposed to episodes of drought. To understand the importance of these issues, it is interesting to look at the case of the American West, which is a relevant illustration of the risks associated with poor management of these reservoirs.

California, Utah, and Arizona are three arid states that rely heavily on underground reserves to meet a large part of their water needs, whether for agricultural irrigation, drinking water supply for communities, or even to support local industries. However, decades of excessive extraction have led to a chronic deficit in groundwater levels, causing major problems.

Sustainable management of these resources requires rigorous conservation measures, increased regulation of extraction, diversification of water supply sources, and investment in research and infrastructure to prevent an imminent environmental and economic disaster. Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) is now recognized internationally as a framework to guide public policy action in the field of water.

2.Agriculture and energy production: economic sectors that consume large amounts of water

Distinction between consumption anduse

The distinction between water abstraction, consumption, and use is essential to understanding the distribution of the resource among economic sectors:

· Water abstraction refers to the quantity of water taken from the natural environment and then discharged after use (and therefore available again).

· Water consumption refers to the fraction of water used that is lost, either through evaporation, infiltration into the ground, or other processes that render the water unavailable for further use.

· Water use refers to how water is used in various sectors such as agriculture, industry, drinking water supply, and sanitation. It encompasses the various applications of water, whether for irrigating crops, cooling industrial machinery, or meeting domestic water needs.

Economic sectors subject to water management issues

Industrial sectors for which water management is crucial include:

- Agri-food, where agricultural irrigation and water treatment are essential for food production;

- The chemical industry, which often requires large amounts of water for chemical reactions and equipment cooling;

- Manufacturing, where water is used in production, cleaning, and waste management;

- The energy industry, which depends on water for electricity generation, particularly in thermal and nuclear power plants;

- And finally, the mining industry, which uses water for mineral extraction and processing.

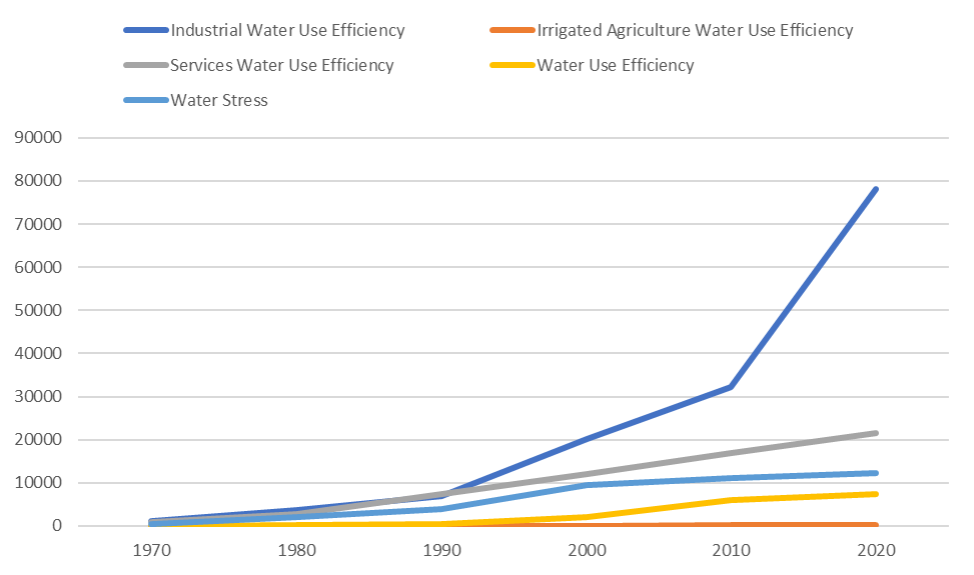

Figure 2:Change in water use efficiency[2] in USD/m3 in agriculture, industry, and services between 1970 and 2020 (FAO 2020)

Focus on agriculture and industry

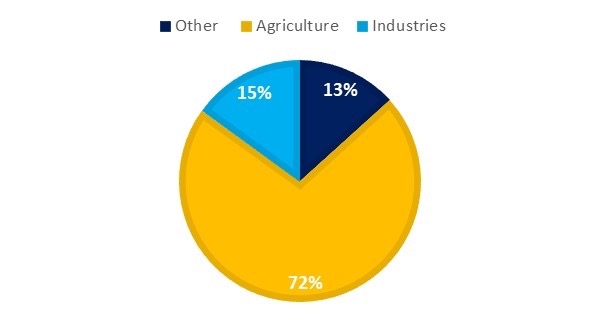

The agricultural sector is the largest consumer of freshwater in the world, accounting for nearly 70% of total freshwater consumption. This reality raises considerable economic challenges, as it has a direct impact on the availability of water for other economic sectors, global food security, and food prices. Irrigation efficiency, agricultural policies, global food markets, and climate change all influence agricultural water demand and associated costs.

Globally, industrial water consumption is estimated to account for about 20% of water consumption. Water is central to many industrial processes and can also be used as a raw material (chemical industry), for washing and waste disposal (food industry), for cooling (steel industry), or to operate boilers (mining industry). Several industrial processes require the use of water, sometimes of high quality. Industries that consume large amounts of groundwater include energy production, mining, construction, and oil and gas extraction.

The analysis of water use by economic sectors can be approached from two angles. On the one hand, the largest consumers are the most at risk in terms of managing this resource, and therefore require both the development of innovative solutions and the definition of a regulatory framework conducive to sustainable water management. On the other hand, they are the most exposed to the risks of drought, which could intensify in certain regions of the world and raise a strategic question: that of the geographical location of sectoral value chains.

Figure 3:Global water withdrawal by the agricultural and industrial sectors in 2020 (FAO 2020).

3.Different types of exposure depending on the country: demographics, geography, anddevelopment

Geographical issues of chronic water stress: the example of the Middle East

The percentage of water stress is generally calculated using a formula that takes into account water availability relative to water needs. This measure is often used to assess water scarcity in a given region or geographical area. According to the UN, a country is considered at risk of water stress when it withdraws more than 25% of its available freshwater resources. For example, in 2018, it is estimated that 18% of global freshwater resources were withdrawn (Food and Agriculture Organization AQUASTAT, 2020).

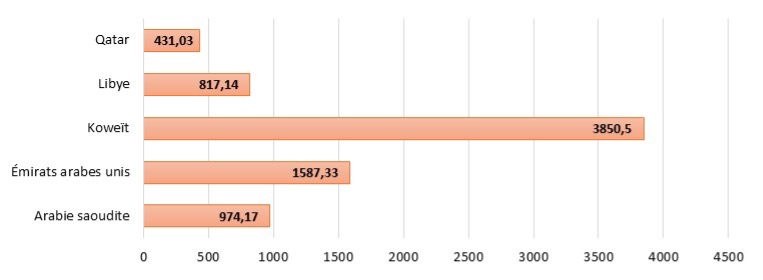

Analysis of FAO water stress data[3] reveals significant disparities between countries. While the average for all countries is 68%, the median for the same data is 10%. Five countries have a level above 400% and are located in arid or semi-arid regions.

Figure 4: Percentageof water stress in 2020 in the countries most at risk

The concentration of these countries in arid regions suggests that water stress issues are strictly geographical. However, two factors must be considered to explain this significant difference with other countries in arid zones: (i) water consumption, particularly for certain industrial uses including the extraction of raw materials, and (ii) water availability.

Demographic issues of high water demand: the emblematic case of China

The dynamic demographics of many Asian countries pose a major challenge for water management. With a rapidly growing population, this part of the world must meet increasing demand for water for agriculture, industry, and domestic needs. This demographic pressure exacerbates the problems of water scarcity, pollution, and water stress in the region.

In China, the equation between demographics and water management is particularly worrying. Although it is the world’s second largest economy and home to 21% of the world’s population, China has only 6% of the world’s freshwater resources (China: A Watershed Moment for Water Governance, 2018). With a population of over 1.4 billion, China faces high demand for water to support its industrial development, rapid urbanization, and intensive agriculture. This demographic pressure exacerbates the challenges of water scarcity, water quality degradation, and water resource depletion. The Chinese government is implementing ambitious initiatives such as dam construction, watershed management, and water conservation policies to address these challenges.

Water management and development

The challenges associated with water management differ between developed and developing countries. While developed countries are implementing regulations related to sustainable water resource management (Law L210-1 of the Environmental Code), some developing countries are struggling to distribute this resource optimally throughout their territory (lack of funding, inadequate infrastructure, social conflicts).

However, in an interconnected world, a natural disaster in a developing country can have repercussions on global value chains. A striking example of this phenomenon is the flooding that occurred in Thailand in 2011, which caused damage estimated at 10% of the country’s GDP and also led to a 2.5% decline in global industrial production (Masahiko & Upmanu, 2015). As Thailand is a major production center for components used in the automotive and electronics industries, the disruption of the supply chain for international companies caused a significant increase in prices, longer delivery times, and a series of combined impacts on other sectors dependent on these products.

Among the findings established by the United Nations in its March 2023 report on water resource development, 2 billion people (26% of the world’s population) still lack access to safe drinking water and 4.6 billion people (46%) do not have access to a safely managed sanitation system. The solutions discussed require international collaboration based on the development of robust mechanisms, particularly when the flow of this resource crosses state borders. Today, only 6 of the 468 shared international aquifers[4] in the world are covered by formal cooperation agreements[5].

Figure 5:Map of country vulnerability to natural disaster risks based on IPCC data (score from 1 to 10)

Conclusion

Several factors specific to the modern world pose significant challenges for the sustainable management of water resources. Between population explosion, global warming, and growing consumption, the respective weight of these factors varies from country to country.

A regional analysis could provide a summary classification of the world’s regions and the factors that are decisive for the management of this resource. According to such an analysis, Asia would be the continent experiencing demographic water stress, the Middle East climatic water stress, and producer countries economic water stress.

In a connected world, the transmission of risk between countries complicates a schematic categorization of the distribution of this resource. The decisive issues for the future will center on international collaboration, adaptation, and resilience for sustainable water resource management.

Bibliography

World Water Development Report. (2022). UNESCO.

Food and Agriculture Organization AQUASTAT. (2020). UN.

WEF. (2022). Ensuring sustainable water management for all by 2030. World Economic Forum.

UNESCO. (2023). Imminent risk of a global water crisis (UNESCO/UN-Water). UNESCO.

Inform Global Index. (2023). IPCC and Columbia University.

FAO. (2020). Water Use Efficiency. Food and Agriculture Organization.

China: A Watershed Moment for Water Governance. (2018). World Bank.

Easterling, D. R., Meehl, G. A., Parmesan, C., Changnon, T. A., Karl, T. R., & Mearns, L. O. (2002). Climate Extremes: Observations, Modeling, and Impacts. Atmospheric Science.

Masahiko, H., & Upmanu, L. (2015). Flood risks and impacts: A case study of Thailand’s floods in 2011 and research questions for supply chain decision making. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction.

Water. (2022). World Bank.

Freshwater: its formation, reservoirs, and available resources. (2021). Water Information Center (CIEAU).

[1] Such as saltwater intrusion into coastal aquifers, land subsidence, and reduced river and stream flows.

[2] A measure that quantifies productivity per unit of water used.

[3] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

[4] Groundwater, as well as surface water, flowing across international borders.

[5] « There is an urgent need to establish robust international mechanisms to prevent the global water crisis from spiraling out of control. Water is our shared future, and it is essential that we act together to share it equitably and manage it sustainably, » says UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay.