Summary:

– The French defined-benefit system makes the pension financing model in France unsustainable: a notional accounts system would avoid further discretionary adjustments.

– The defined contribution system implemented in Sweden treats pensions as an adjustment variable.

– Pensions are calculated based on life expectancy and changes in average wages. This mechanism guarantees budgetary balance but can also lead to a loss of real purchasing power if income growth is lower than price growth or if life expectancy increases.

– However, the system remains flexible and is guaranteed by a minimum pension system financed by income tax. This is an exemplary model for structural reform of the pension financing model in France.

While discussions on financing and retirement age are intensifying in France, Sweden offers an example of a country that has successfully transitioned from a system similar to the current French system in the early 1990s to a financially sustainable and self-correcting system that addresses population aging and economic cycle variations. But how does this system work? And could it be applied in France?

First solution for the current situation: a parametric reform (the French model)

In France, the current pension system is largely a pay-as-you-go system. This means that current contributions paid by employees and employers finance the current pensions of retirees. It is a defined-benefit system: the amount of pensions is guaranteed at the time of retirement. If the system becomes financially unsustainable, a parametric reform is needed to increase the total amount of contributions and thus pay the guaranteed pensions of retirees. Contributions can be increased in three ways:

(1) increasing the contribution rate for active workers,

(2) increasing the number of contribution years

(3) raising the minimum legal retirement age

(4) changing the amount of pension revaluation, for example by de-indexing it from inflation (this is the case with the recently signed agreement on supplementary pensions).

However, changing these four parameters only solves the problem temporarily, as it does not shift the burden of the reforms onto the working population. It is therefore reasonable to question the merits of a « systemic » reform proposed by economists Thomas Piketty and Antoine Bozio in their research paper « Pensions: towards a system of individual contribution accounts – Proposals for a general overhaul of pension schemes in France. »

Second structural solution: a « notional accounts » system (the Swedish model)

In France, the rules for calculating pension amounts are complex, with differences depending on the pension plan (basic or supplementary) and the type of employment (managerial or non-managerial, public or private, special plans, work abroad). This difficulty in calculating pensions calls into question the basic principle of « equal contributions, equal pensions. » How can it be justified that two people who have contributed the same amount throughout their careers do not receive the same pension when they retire?

This is where the Swedish model and the « notional accounts » system come in. This type of pension system is no longer a defined-benefit system, but a defined-contribution system. The level of pensions is the adjustment variable (whereas contributions are the main adjustment variable in the current French system), i.e., the amount of pensions paid to retirees is not guaranteed « a priori, » but is defined at the time of retirement, based on three main criteria: the amount of contributions paid by the individual, the estimated life expectancy of their generation, and their retirement age. There is therefore no legal retirement age; every Swede can decide to retire when they wish, between the ages of 61 and 67.

For example, according to the IREF report « The Reform of the Swedish Pension System, » taking as a reference an employee who decides to retire at age 65 and receives a pension of €2,000 per month, they could have chosen to retire at 61 and receive €1,440 per month (72% of their « normal » retirement pension at 65), or to delay their retirement until 67 and receive a pension of €2,380 per month (119% of their « normal » retirement pension at 65). More years of work means more contributions: the length of time a retiree receives their pension therefore decreases and their monthly pension increases.

According to the IREF, this new system would encourage those who wish to do so to work longer, while still allowing people who want to retire at 61 to do so. But what is the reality? Does it really promote employment among older people? According to a study by the Schuman Foundation (« Pension systems in the European Union« ), Sweden is the country in Europe with the highest employment rate among older people (72.1%). In France, only 41.4% of 55-64 year olds are still in employment. This is a significant difference, even though the unemployment rate in Sweden (8.5%) remains lower than that in France (10.6%).

A system with a balanced budget that is more equitable than the parametric reform model

The Swedish system is a pay-as-you-go system, but one that is designed to remain balanced. Each active worker sets up a « virtual » individual account (no real capital is accumulated): the amounts contributed are used to finance current pensions. This virtual capital is revalued each year and isultimately converted into a life annuity when the pension is paid out. At the time of retirement, the level of the pension will then depend on three parameters:

(1) the amount of virtual capital;

(2) the generation to which the insured person belongs;

(3) the age at which they choose to claim their pension.

In addition to being more transparent, the notional accounts system tends to be more equitable. In France, the level of the pension is based on the x best years of salary (or simply on the last year for civil servants). This tends to disadvantage the poorest employees, for two reasons:

(1) blue-collar workers often have little variation in their salaries throughout their careers (e.g., minimum wage throughout their lives) and contribute for more years (because they have fewer years of education).

(2) the life expectancy of poor employees at retirement is lower than that of wealthy employees.

The notional accounts system does not solve the second problem, but by taking into account all the contributions paid throughout each individual’s career (and not just the x best years), it restores a little more equity by reducing the average wage differential between « blue-collar » and « white-collar » workers.

A very clear graph in the Senate report (« Pension financing: the exemplary success of the 1998 reform« ) shows in detail how the Swedish pension system works. Throughout their career, individuals contribute to their pension and build up virtual capital (shown in red on the graph). This capital is revalued according to a net interest rate, which takes into account management costs, changes in average wages, and « inherited gains, » i.e., pension benefits not used by people who died prematurely and which are shared among all surviving social security contributors. When the insured person wants to retire, their life expectancy is calculated (based on their age and medical advances) and a conversion coefficient is applied, which takes into account a return r attributed to capital C (return standard set at r = 1.6% per year).

Thus, when life expectancy increases, an employee must contribute more or work longer to receive the same level of pension. This mechanism is independent of parametric reforms (pension revaluation, increase in contribution rates, contribution periods, minimum legal retirement age) by self-regulating according to changes in life expectancy and average wages. This system makes the risk of a deficit dependent on a very sharp increase in life expectancy. The system therefore has a high probability of being in budgetary equilibrium.

Two disadvantages of the « notional accounts » system

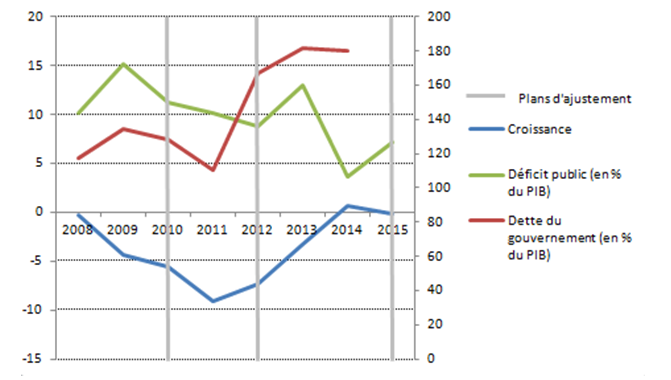

Firstly, indexation based not on inflation but on changes in average income may, in times of crisis when inflation exceeds changes in average income, lead to a loss of purchasing power, i.e., a negative change in the real value of pensions.

Secondly, self-regulation of the retirement age based on life expectancy may require people to work longer without seeing any increase in their pension level. According to calculations by the Swedish Pension System, a person born in 1990 will have to work approximately 26 months longer to receive the same level of pension as a person born in 1940 (for an additional life expectancy of 41 months).

However, a minimum pension is guaranteed. This is the case for people who have never paid contributions in their lives (due to physical inability to work) and who have lived in Sweden for at least 40 years. This guaranteed pension is not financed by contributions but by income tax (like other solidarity mechanisms). In 2004 in Sweden (figures from the IREF report), this guaranteed minimum pension was €8,300 per year. This amount is equivalent to the French « minimum vieillesse » (minimum old-age pension), which is based on the same principle.

The systemic reform in Sweden took twelve years to implement

This systemic pension reform in Sweden did not happen overnight. The first review committee was held in 1991, and the first pension payments based on the new system were not made until 12 years later, in 2003.

Despite changes in government, Sweden successfully implemented this ambitious reform. It was a long-term political process that reflected the desire for a transparent and fair pension financing mechanism that would ensure budgetary balance.

These three characteristics could inspire France’s next structural policy.