Haddad, Valentin, Paul Ho, and Erik Loualiche. “Bubbles and the Value of Innovation.” Journal of Financial Economics 145,no. 1 (July 2022): 69–84.

Abstract:

- Economic theory has demonstrated the existence of market failures leading to structural underinvestment in innovation.

- However, this reality is not incompatible with the existence of bubble episodes.

- This article shows that there is a decorrelation between the value of a company and its innovation when the sectors in which it operates are experiencing a bubble. The authors explain this phenomenon by a disagreement among investors.

It is commonly believed that fluctuations in share prices following the announcement of an innovation reflect the change in the company’s present value. This simple principle is still at the heart of research on the subject today. However, the potential presence of bubbles contradicts this view.

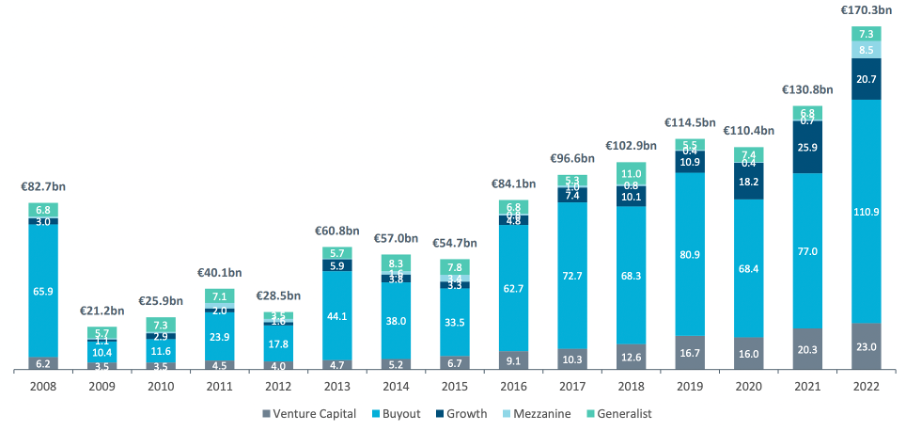

A bubble corresponds to a generalized decorrelation between the capitalization of companies and the value of their underlying assets… in other words, an overreaction by investors to the announcement of an innovation relative to the actual cash flows generated by it. The recent bankruptcy of Silicon Valley Bank, which was particularly weakened by the recent downturn in tech company valuations, reminds us that this principle remains just that—a principle—because there can be exceptions. This is an even more critical issue given that the 2010s were marked by strong growth in the venture capital segment, which finances innovative companies and startups. The total amount invested in innovative sectors has thus reached historic levels.

Figure 1 – Growth in assets under management in the private equity segment in Europe and historic peak in the venture capital segment (mainly intended to finance young and innovative companies).

Source: Invest Europe

So what about the risk of a bubble in innovation? In their article Bubbles and the valuation of innovation(July 2022), V. Haddad, E. Loualiche, and P. Ho attempt to understand the mechanics at play in such phenomena and measure their scale. They demonstrate that episodes of speculative bubbles on the value of innovative companies can be identified in several sectors. These bubbles often coincide with periods of intense innovation. The authors also offer a theoretical model to explain this phenomenon, based on the fundamental hypothesis of disagreement among potential investors in a world of incomplete information.

1. At the heart of the bubble phenomenon lies a potential disagreement among investors

Before embarking on an empirical analysis, the authors propose a theoretical model that transparently and rigorously illustrates the potential mechanisms at work in the formation of bubbles in the valuation of innovations.

The model is dynamic, spanning two discrete periods over time. The economy is summarized as the interaction between two types of actors: households and entrepreneurs. This is therefore a simplified view of reality, allowing us to focus on the essential mechanisms. During the first period, households generate ideas that they sell to entrepreneurs to start businesses. They also invest in the capital market in companies created from their projects. During the second period, the companies have been developed and compete with each other to sell goods and services. Households receive dividends from their investments and consume.

This model shares many similarities with previous work on business valuation. However, the authors introduce one new feature: divergence in household beliefs. This feature makes it possible to explain the empirically observed results. Households have different expectations about the future productivity of businesses. Information is imperfect and there is a lack of data to measure the real credibility of each company. However, the size of the market is known and is less than the total capacity of the various competitors created. Not all of them will sell. Each household is nevertheless convinced that the companies in which it invests will be more productive than average and will therefore win a share of the market. The price of each company is the expected value of its profits according to economic theory. But since expectations exceed the size of the market, the rest is self-evident.

2. Speculative bubbles in innovation exist regardless of the sector and coincide with periods of strong innovation momentum.

The main question raised by the article is whether there is a decorrelation between the valuation of innovative companies and their cash flows during periods of intense activity in their sector, identified as a bubble.

To answer this question, the authors define two key concepts. The bubble is defined according to the work of Greenwood, Scheifler, and You (2019). A sector experiences a bubble in a given month if it meets three cumulative criteria. First, the value-weighted portfolio of the industry has returned 100% or more over the past two years. Second, the value-weighted return of that sector also exceeds the market return by at least 100% over the past two years. Third, the value-weighted return of the industry over the past five years is greater than 50%. Innovation valuation is defined as the stock market’s reaction within three days of a company issuing a new patent, taking into account the return of the stock portfolio during that period.

Empirically, the article therefore links this valuation of innovation to whether or not we are in a bubble period (dichotomous variable), all other things being equal. Two main findings emerge from this work:

- First, the valuation of companies filing for innovation increases very sharply during a bubble period, by 30 to 50%—depending on whether it is measured at the company or patent level. However, actual results (profit and productivity) do not seem to be affected.

- Second, the authors identify a lack of correction in the valuation of competitors. Some studies in the literature have clearly identified the negative effects of a company’s innovation on its competitors. Contrary to these results, the authors show that during a bubble period, the market tends to ignore these negative externalities. Outside of bubble periods, this problem does not seem to exist, and the market reacts significantly to the announcement of an innovation by a competitor.

The authors point out that bubbles are often observed during periods of strong innovation within a sector . Their results therefore tend to show excessive market optimism regarding the valuation of innovations in sectors experiencing strong activity. This phenomenon tends to fuel the existing boom. The link between innovation and bubble formation, although poorly understood, appears to be strong.

Conclusion: Why is this vision innovative and what can we learn from it?

According to the authors, this paper contributes one main idea to existing research. Disagreement among investors leads simultaneously to overinvestment in innovative companies and a lack of market correction of the value of their competitors. Among other things, this idea seems to echo certain proclaimed investment races motivated by the belief that » the winner takes all. »

These disconnections are not without real consequences. The authors discuss potential measures that could be taken by public authorities to limit the risk of bubbles. One such measure would be to impose increasing taxes on new entrants creating a company based on an idea that has already been exploited. This solution faces many difficulties. However, this paper raises a key question that is deeply rooted in recent events. Further studies will be needed to challenge both the empirical results and the theoretical model.