Abstract:

– Contrary to popular belief, the link between immigration and lower wages or higher unemployment is far from proven.

– Although immigrants receive more social benefits on average, their overall net contribution to the national budget remains positive.

– While migration policy alone cannot solve the problems associated with an aging population, it can temporarily ease the tax burden.

Immigration fuels public debate, even though the scale of this phenomenon is often poorly understood (see the article by the same author on the BSI Economics website , » Immigration in France: what is the reality? « ).

Immigration is often perceived as a source of problems for the populations of host countries. In 2013, 50% of French people believed that immigration was more a source of problems than of opportunities (Transatlantic Trends on Immigration, 2014). Fears generally focus on two main aspects: the effects of immigration on the labor market and on the national budget.

Immigration and the labor market

Immigration is often blamed for being partly responsible for lower wages and higher unemployment. However, these relationships are far from obvious.

Immigration and wages

Migration flows mean labor flows, especially since immigrants are overrepresented in the age groups considered to be active (see the article » Immigration in France: what is the reality? » on the BSI Economics website). Immigration therefore has the effect of increasing the labor supply. In a model of pure and perfect competition, where wages are set freely at the intersection of labor supply and demand (no rigidity), all other things being equal, this increase in the supply of labor leads to a fall in wages. However, this view is somewhat simplistic and several cases need to be distinguished.

First, in many developed countries, there are wage rigidities, such as the existence of a minimum wage, which prevent wages from varying according to simple market laws. If the additional labor supply resulting from the influx of migrants implies an equilibrium wage below the minimum wage, the adjustment will not be made through the price of labor (wages are rigid) but through quantities. Wages will therefore not fall, but there is a risk of increased unemployment. We will return to the link between immigration and unemployment below.

A second problem is that the reasoning outlined above assumes that all other things remain equal. However, migration flows will affect not only the labor supply but also other macroeconomic variables. As capital becomes scarcer relative to labor, its return should increase, generating a growth in capital (Chojnicki and Ragot, 2012). This investment generates an increase in production capacity, which adapts to the surplus labor. In this context, the decline in wages would only be temporary.

Finally, the third criticism is that pure and perfect competition reasoning also assumes that native and immigrant workers are homogeneous and substitutable, which is clearly not the case. As we have seen, workers from migratory flows are, on average, less educated, yet unskilled workers are not substitutable for skilled workers. Thus, the influx of unskilled migrants leads to an increase in the unskilled labor force and therefore to a decline in wages for unskilled workers (Chojnicki and Ragot, 2012). At the same time, as skilled labor becomes relatively scarcer, the wages of skilled workers will increase. It is therefore possible that immigration goes hand in hand with an increase in wage inequality.

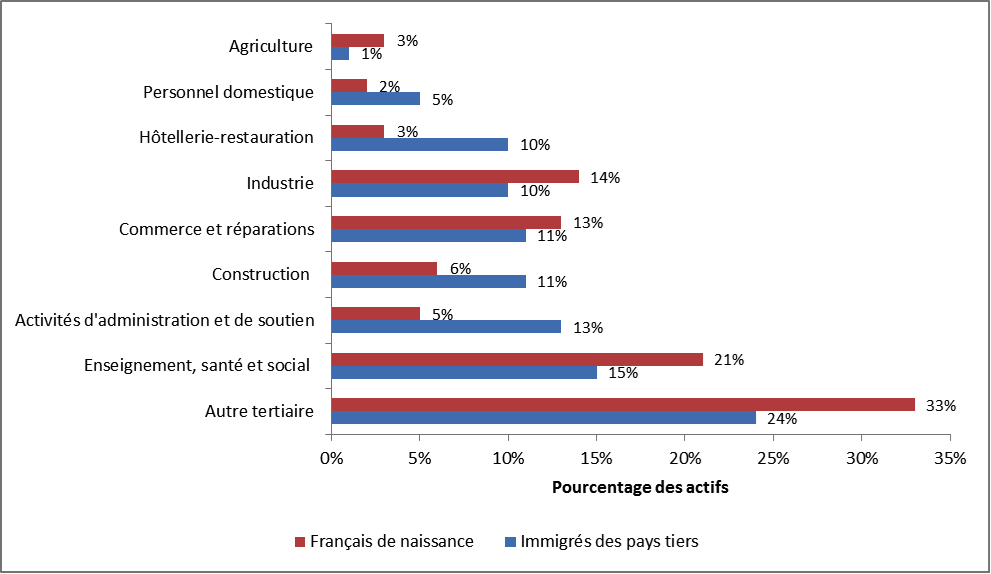

Even with similar qualifications, immigrant and native workers are not necessarily substitutable. The labor market is highly segmented, and many immigrants occupy jobs not filled by native workers. In 2012, immigrants from third countries (outside the European Union) were overrepresented in the hotel and restaurant industry, support activities, and construction (Figure 1). Immigration therefore helps to ease certain tensions in the labor market. In this case, according to the complementarity hypothesis, the arrival of new migrants will not affect the wages of native workers but will lead to a decline in the wages of migrants already present.

Figure 1: Sectors of activity of the working population

Sources: Author, DSED data (2014), BSI Economics

The theory therefore highlights several links that may be contradictory and do not allow us to draw direct conclusions about the true impact of immigration on wages. It is therefore necessary to look at the empirical side. The most comprehensive studies on the subject refute the potential existence of a link between immigration and lower wages (Docquier et al., 2010; Ortega and Verdugo, 2011; Ottaviano and Peri, 2012). On the contrary, these studies tend to show that immigration has led to an increase in the wages of native workers. Ortega and Verdugo (2011) estimate that a 10% increase in immigration leads to a 3% increase in the wages of non-migrants.

Immigration and employment

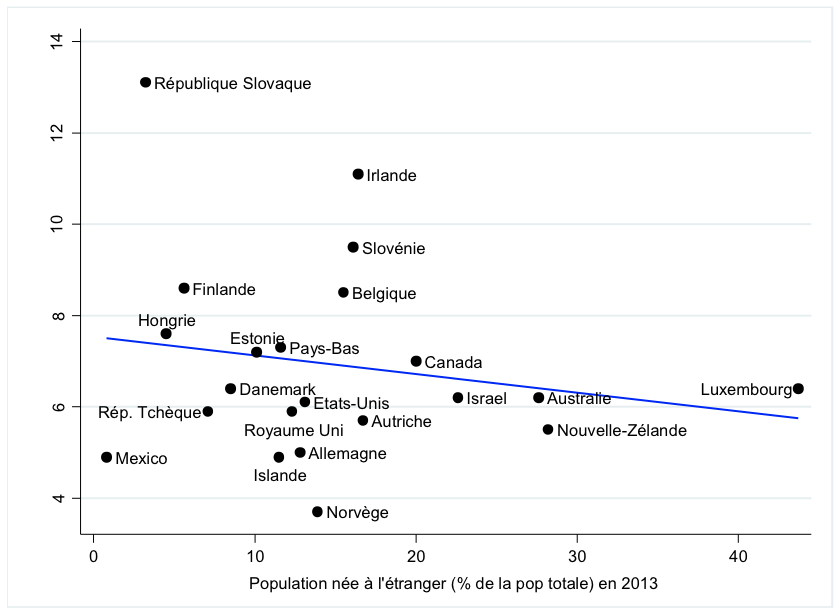

Still in relation to the labor market, immigration is also often blamed for unemployment. However, the link between unemployment and immigration is far from clear (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Immigration and unemployment rates

Sources: Author, OECD data, BSI Economics

Several phenomena call into question the link between immigration and unemployment. First, migration flows increase not only the supply of labor but also demand through consumption, which stimulates activity and potentially creates jobs (Ortega and Peri, 2009).

As noted above, migrants and natives are not perfectly substitutable and do not occupy the same jobs (Figure 1). Immigrants therefore do not compete with natives but help to meet a different demand for labor, thereby easing certain tensions in the labor market (Chojnicki and Ragot, 2012).

These theoretical considerations have been confirmed by several empirical studies. For example, whether it be Card (1990) in his study on the mass arrival of Cubans in Florida in 1980, Hunt (1992) on the repatriation of pieds noirs from Algeria in 1962, or Friedberg (2001) on the immigration of Jews from the Soviet Union to Israel between 1990 and 1991, all these authors show that immigration has no effect on unemployment or that this effect is only temporary and very weak.

Immigration and taxation

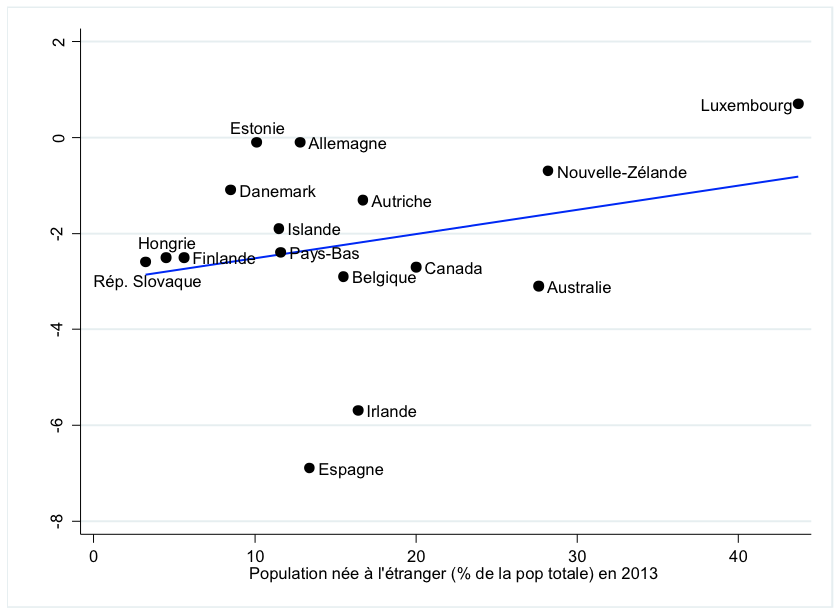

In addition to fears about the labor market, immigration is often perceived as a factor that exacerbates the public deficit, the argument being that immigrants receive more social benefits than they contribute. An initial analysis linking the public deficit to the percentage of the population born abroad shows that this fear is not necessarily well-founded (Figure 3).

Figure 3: General government deficit and percentage of the population born abroad

Sources: Author, OECD data, BSI Economics

On average, however, immigrants in France make greater use of social benefits, particularly the RMI (minimum income allowance) and unemployment benefits, even after taking into account differences in individual characteristics (age, gender, education, etc.) (Chojnicki and Ragot, 2012). This result can be explained by greater exclusion from the labor market or by the rational behavior of immigrants who are satisfied with simple assistance because it represents a substantial income compared to their income in their country of origin. However, while immigrants receive more social transfers, they also contribute to the system through their contributions. It is therefore important not to stop at this simplistic view but to look at the net contribution of immigrants. Chojnicki and Ragot (2012) show that, taking into account the age structure of the immigrant population, which is younger, the overall net contribution of immigrants to public budgets is positive, even if it remains relatively low (0.5% of GDP). For a given age, the net contribution of an immigrant is lower than that of a native, but since immigrants are younger, the overall effect is positive.

Immigration and population aging

Developed countries are currently experiencing population aging. In France, according to INSEE projections, if the current trend continues, one in three people will be over 60 in 2060. This aging population raises many questions, particularly in terms of financing pay-as-you-go pension systems. As the immigrant population is relatively young, immigration could therefore provide a temporary solution to this problem by increasing the proportion of the population of working age.

However, it is difficult to imagine that migration policy alone could provide a solution to the aging population. Chojnicki and Ragot (2012) show that maintaining the dependency ratio[1] at its 2010 level through migration policy alone would require annual migration flows of several million people, which would double the population by 2050 and increase the share of immigrants in the total population to 41%. Moreover, immigrants will also eventually grow old, so in the long term, the aging of the population will not be resolved.

While not a miracle solution to aging, an enlightened migration policy could temporarily ease the fiscal burden associated with aging. On the contrary, reducing migration flows would only increase the fiscal cost. Chojnicki and Ragot (2012) compare two scenarios. The first scenario is based on observed migration flows (baseline scenario), while the second is based on zero migration flows. The result is clear. Without migration flows, the estimated total population will fall by 10% in 2050 compared to the baseline scenario, leading to a decline in GDP and an increase in the dependency ratio of 3.8 points. These two effects will result in an increase in spending of 1.3 points of GDP.

Conclusion

Immigration is a phenomenon that fuels much debate, yet its effects are not well understood or appreciated. The idea that immigration is responsible for lower wages or higher unemployment is based on strong assumptions, particularly that of labor homogeneity. There is no evidence that migration flows lead to lower wages or higher unemployment among native-born workers.

As for the national budget, even if immigrants receive more social benefits, the immigrant population makes a positive net contribution overall due to its age structure. While immigration alone cannot solve the problem of an aging population, it does help to reduce the fiscal cost.

References:

– Card, D. (1990). The impact of the Mariel boatlift on the Miami labor market. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 43(2), 245-257.

– Chojnicki, X., & Ragot, L. (2012). We hear that immigration is costly for France. Editions Eyrolles.

– Docquier, F., Özden, Ç., & Peri, G. (2010). The wage effects of immigration and emigration ( No. w16646). National Bureau of Economic Research.

– DSED (Department of Statistics, Studies, and Documentation) (2014), “Activities of immigrants in 2012,” Info migrations, no. 60

– Friedberg, R. M. (2001). The impact of mass migration on the Israeli labor market. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1373-1408.

– Hunt, J. (1992). The impact of the 1962 repatriates from Algeria on the French labor market. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 45(3), 556-572.

– Ortega, J., & Verdugo, G. (2011). Immigration and the occupational choice of natives: A factor proportions approach.

– Ortega, F., & Peri, G. (2009). The causes and effects of international migrations: Evidence from OECD countries 1980-2005 ( No. w14833). National Bureau of Economic Research.

– Ottaviano, G. I., & Peri, G. (2012). Rethinking the effect of immigration on wages. Journal of the European Economic Association, 10(1), 152-197.

– Transatlantic Trends: Mobility, Migration and Integration, 2014