Summary:

– France is struggling to maintain its market share on the international stage, which is preventing it from finding external sources of economic growth at a time when the domestic situation is difficult.

– Numerous measures have been implemented to restore cost competitiveness, but their effects are expected in the medium/long term.

– Other levers could therefore be activated to increase the attractiveness of French exports in the shorter term.

The lack of economic dynamism in the eurozone remains a major concern. Recently, the IMF and the OECD once again expressed their concern about this situation. Within the eurozone, France is going through a difficult period, with growth forecasts for 2014 revised down to 0.4% (from 1% previously).

Numerous measures have been implemented to address this bleak outlook. Among these, there has been much discussion about France’s position and strengths in international trade, focusing in particular on the competitiveness of French companies on the international stage. Indeed, while exports could support growth (I), it is certainly important to consider the factors influencing cost competitiveness (II), but also the possibilities of implementing other levers that could reduce export costs (III).

Exports to offset sluggish domestic demand?

In the second quarter of 2014, as in the first, French GDP growth was zero (+0% quarter-on-quarter), suggesting relatively weak annual growth for 2014 (growth in the first half of the year is now 0.3%). This weak economic activity is shared by many countries in the eurozone, where the effects of the crisis are still being felt.

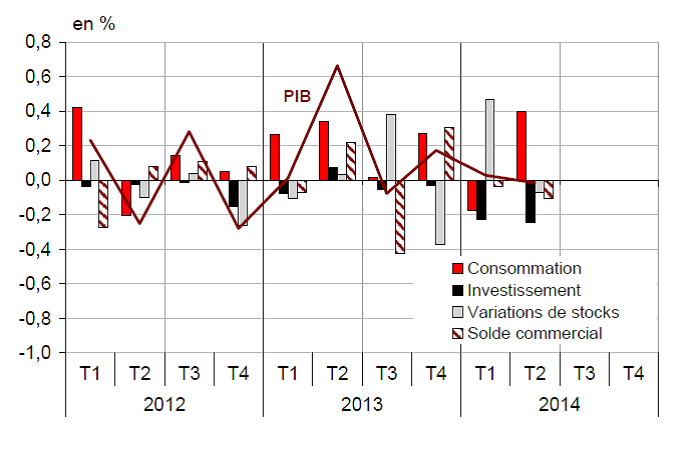

Figure 1: French GDP and its components

Sources: Macrobond, INSEE, BSI Economics

A look at the components of GDP in France highlights weak consumption and a lack of investment, which are usually the main contributors. In addition, high unemployment continues to weigh on household confidence, which is likely to have a downward impact on consumption, particularly private consumption.Finally, the household savings rate remains historically high in a context where precautionary savings are still significant. After standing at 15.1% and 14.7% in the third and fourth quarters of 2013 respectively, it reached 15.9% in the first quarter of 2014.

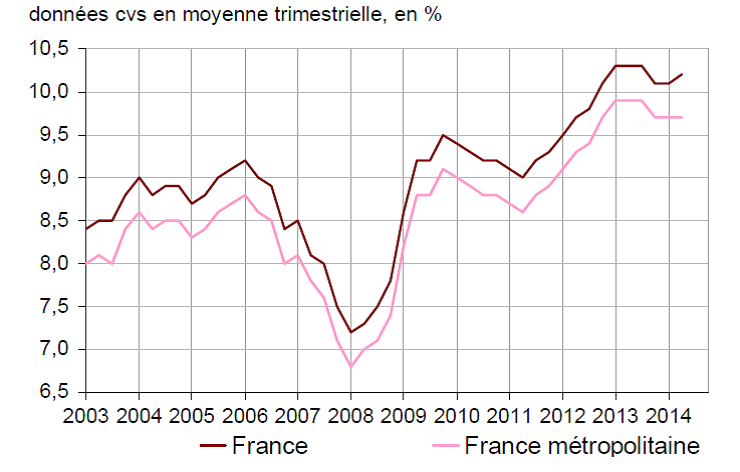

Figure 2: Unemployment trends (ILO definition) in France (source: INSEE, Macrobonds, BSI Economics)

At the same time, while imports remain high, the lack of momentum in French exports is preventing French companies from finding the foreign markets that they seem to be lacking within the national economic area. The external drivers of French economic growth are therefore also relatively weak, as reflected in the sluggish trade balance, which remains negative, leading to a negative contribution from foreign trade to growth. In light of this, it is important to examine the determinants of French export costs.

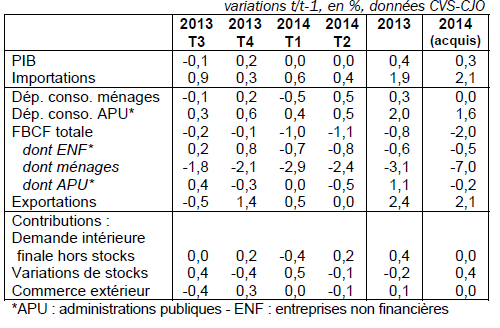

Table 1: French GDP and its components

Source: INSEE

An approach based on cost competitiveness: CSU and export prices

In order to explain the difficulties French companies face in exporting and thus to remedy them, various explanations have been put forward, such as a lack of cost competitiveness characterized by (1) unit labor costs (ULC) and (2) export price levels.

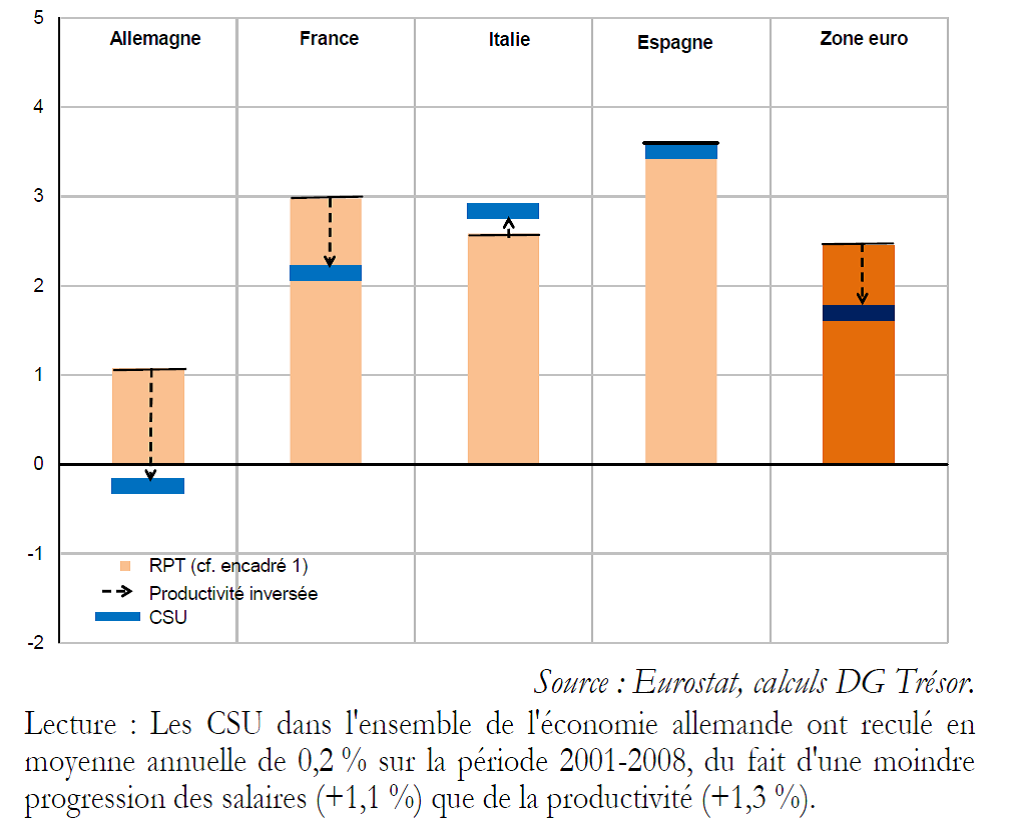

Firstly, the upward trend in ULC since 2001 is said to have had a negative impact on the cost competitiveness of companies. Before 2008, they grew at a faster rate than the eurozone average, driven in particular by wage increases. This increase continued, albeit at a more moderate pace, after 2008.

Figure 3: Contributions to the average annual growth rate of UCCs in the economy as a whole over the period 2001-2008

Source: DG Trésor[1]

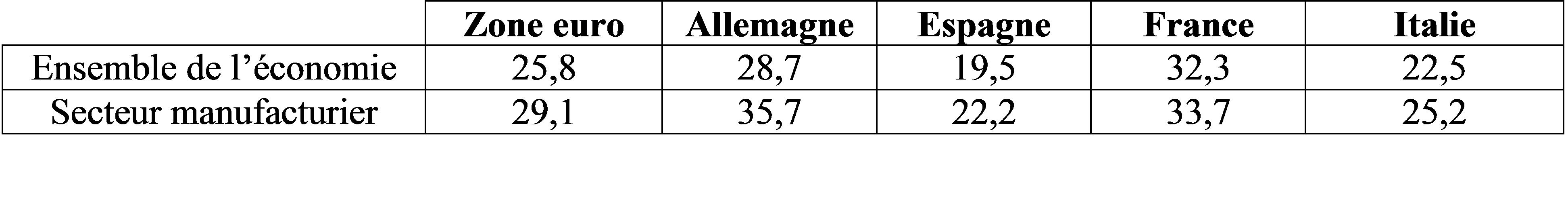

Secondly, beyond this dynamic view offered by changes in ULCs to estimate productivity growth, export decisions are also influenced by the cost levels of French products at a given moment and, in particular, their relative cost compared to other products on globalized markets. It may therefore be useful to compare these costs in terms of level, particularly production costs, in order to determine their share in the obstacles to French companies’ integration into international trade and the development of exports. It is instructive, for example, to look at gross wages. Here again, France stands out, with French wages appearing to be higher than those in other countries, particularly in relation to those in the Eurozone that export to comparable market segments.

Table 2: Wages in euros per hour worked in 2013 (source: Eurostat)

In addition, the strength of the euro (particularly against the US dollar) since the early 2000s has doubled these comparative cost disadvantages, with a negative impact on price competitiveness, as exchange rates have a strong influence on the latter, particularly in markets where trade is conducted in dollars (this is the case, for example, in the aerospace industry).[2].

To cope with these various constraints and maintain competitive prices, French companies have been forced to reduce their margins. The margin rate (gross operating surplus over value added) of French non-financial companies reached its lowest level since 1985 in 2013, standing at 29.7% according to INSEE[3. This squeeze on margins further increases these companies’ financing difficulties and limits their investment capacity to improve non-price competitiveness (investment in research and development, capacity expansion, promotion of innovation, improvement of product quality), thereby hampering their long-term growth and their ability to develop comparative advantages for the future.

This trend therefore prevents companies from taking full advantage of international trade and contributes to undermining France’s capacity for innovation, which may have long-term negative impacts on potential growth.

Various levers could be used to develop an export-friendly economic policy over time

Several reforms have been decided and implemented in France to address this issue: the CICE[4]and the Responsibility and Solidarity Pact are two recent examples. The aim of these reforms is to reduce production costs, particularly through lower labor costs, in order to improve the competitiveness of French products and boost French exports, while enabling companies to generate margins. Such a development should ultimately trigger a virtuous circle, by encouraging investment and innovation, which should support and boost non-price competitiveness.

Similar reforms were implemented in Germany in the 2000s, such as the various Hartz reforms.[5], with the aim of reforming the German labor market. Given the current export performance of German companies and the low unemployment rate, the structural reforms undertaken have borne fruit[6].

However, before jumping to conclusions about the beneficial effects of these reforms, two points should be emphasized:

– These reforms were implemented in a different global macroeconomic context, where world economic growth (particularly in other developed economies and the eurozone) was stronger and the eurozone was not affected by fiscal contractionary measures. This may have mitigated the negative impacts of these structural reforms.

– These reforms then took time to produce positive effects, particularly on the labor market.

Given this observation, and considering the need to rapidly develop new growth drivers for businesses in order to limit the rise in unemployment, other avenues could be explored. This is particularly the case when considering French exports, which can be supported by other means.

Firstly, action can be taken to facilitate the financing of exports, which can help to reduce export costs. This is all the more important given that changes in financial regulations, as part of the Basel III reforms, will place significant constraints on banks’ balance sheets and potentially increase the cost of financing for exporting companies. Banks could then decide to refocus their activities on sectors that are less risky or more profitable than export financing (particularly by reducing export credit). Furthermore, since the 2007 crisis, banks’ financing costs have increased, thereby increasing the costs of certain activities. Overall, the costs of certain products involved in export financing (such as export credit) have risen compared to the pre-crisis situation.

The government could therefore provide direct assistance to exporting companies or facilitate financing for banks operating in the export financing market (for example, by facilitating the guarantee and insurance mechanisms already implemented as part of Coface’s activities or by facilitating bank refinancing). Such measures would reduce the capital cost of exports in the short term, which would help to restore their welcome dynamism.

At the same time, it could be beneficial to harmonize and improve the effectiveness of all the public policy tools supporting exporting companies(harmonization of the international networks of the various administrations, support for companies throughout their development, etc.). The support of a highly structured and coherent international network would, in particular, enable genuine support for French SMEs internationally, which have so far struggled to establish themselves on the world stage.

In the long term, the observed cost competitiveness deficits must be eliminated in order to restore French exports to their full potential. The effects of the structural reforms implemented with this in mind will therefore be decisive for future economic growth and the ability of French companies to participate positively in international trade. As such, they will be closely analyzed and studied in the future. However, they may take a long time to materialize, and other levers could be used to develop support for exports in the short term.

Conclusion

Thus, beyond the necessary reflection on France’s production costs and cost competitiveness, short-term support for French exports could come from the implementation of mechanisms. These would help to reduce export prices, in particular through measures to facilitate export financing, while making the interactions between the various public policy tools supporting exporting companies more transparent. Such a development would enable France to generate the growth drivers it needs in the short term without compromising the debate on France’s competitiveness and long-term economic growth.

Notes:

[1] See in particular How do unit labor costs in France compare with those of other Eurozone countries?, Ciornohuz C. and Darmet-Cucchiarini, M., Trésor-éco No. 134, September 2014.

[2] However, the importance of the exchange rate should not lead us to conclude that the euro is overvalued (see Bénassy-Quéré (2014)).

[3] It stood at 29.5% in thethird quarter of 2013, 29.4% in thefourth quarter of 2013, and 30.0% inthe first quarterof 2014, according to INSEE.

[4] Tax credit for competitiveness and employment: find an analysis of the CICE on the BSI Economics website by clicking here.

[5] There were four Hartz reforms (between January 2003 and January 2005), which were accompanied by other structural reforms of the German labor market. Find an article by BSI Economics on the subject by clicking here.

[6] However, this has had a negative impact on inequality within the country.

Bibliography:

– Bénassy-Quéré A., Gourinchas P.-O., Martin, Ph. and Plantin, G. (2014), The euro in the « currency war, » Note from the Economic Analysis Council

– Bouvard F., Rambert, L., Romanello, L. and Studer, N. (2013), Hartz reforms: what effects on the German labor market?, Trésor-éco No. 110

– Ciornohuz, C. and Darmet-Cucchiarini, M. (2014), How do unit labor costs in France compare with those of other eurozone countries?, Trésor-éco No. 134

– Fromentin, J.-C. and Prat, P. (2013), Information report on the evaluation of public support for exports

– Krebs, T. and Scheffel, M. (2013), Macroeconomic evaluations of labor market reform in Germany, IMF Working Paper, WP/13/42