As part of the energy transition, the increase in the share of non-controllable renewable energies in electricity generation and the electrification of uses are complicating the supply-demand balance. However, electricity market prices are encouraging flexible sources to make the necessary adjustments to ensure grid stability. Several sources of flexibility are crucial: gas-fired power plants, storage units, international interconnections, and demand response, increasingly involving industrial and residential consumers in modulating their consumption.

Electricity markets are subject to very specific constraints related to the very nature of electrical systems. The balance between supply and demand must be maintained at all times, otherwise there is a risk of partial or total power outages.

In the context of the energy transition, this equation is becoming increasingly complex. To reduce the carbon footprint of final energy consumption, which is still 49.5% dependent on carbon sources in France[1], the expansion of renewable sources and the increasing electrification of energy uses are necessary[2]. However, the simultaneous adoption of these measures leads to significant imbalances between electricity supply and demand.

1) Complexity of the supply-demand balance in the transition

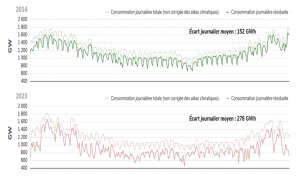

To quantify these imbalances, we use the concept of residual demand. This is calculated by subtracting the production of non-controllable renewable energies, such as solar and wind power, from total electricity consumption. Residual consumption thus reflects the amount of electricity that must be supplied by other controllable means of production or that must be reduced to restore balance [3].

As shown in Figure 1, the gap between total consumption and residual consumption in France increased between 2014 and 2023 due to the growth of renewable energies, which are meeting an increasing share of demand. During this period, the capacity of France’s solar photovoltaic fleet more than tripled, from 6.1 GW to 19.0 GW, while the capacity of the wind farm fleet more than doubled to reach 21.8 GW in 2023 [4].

Figure 1: Total consumption (unadjusted for climatic variations) and residual consumption in 2014 and 2023 (Bilan Electrique 2023, RTE)

However, Figure 1 also shows an increase in the volatility of residual demand between 2014 and 2023, due to the non-controllable nature of renewable energies and the increase in consumption peaks linked to the electrification of heating, for example. The more volatile residual demand is, the more the transition of the electricity system must take imbalances into account. This poses challenges for grid stability and requires greater flexibility to adapt effectively to fluctuations in supply and demand.

2) Electricity Market: Prices, Adjustments, and Flexibilities

In the electricity market, the management of imbalances between supply and demand is based on the mechanism of supply-demand equilibrium pricing. If demand increases for a given level of supply, the price of electricity per MWh increases, and vice versa. In addition, this system follows an order of priority: the least expensive power plants, such as renewable, hydroelectric, and nuclear sources, are used first, followed by more expensive power plants, such as those running on gas or oil, until demand is met. The structural imbalances resulting from the energy transition therefore require greater adaptation of demand to supply, as the latter is increasingly less based on controllable fossil fuel power plants. The current market mechanisms thus make these adjustments in demand increasingly attractive.

A prime example of this dynamic is taking place in California during the summer months, where the abundance of solar energy poses problems for the electricity system. When the supply of renewable electricity significantly exceeds demand, electricity prices can fall sharply, sometimes reaching negative values on the market. This situation raises concerns about the profitability of renewable energy infrastructure. However, an abundance of non-controllable renewable electricity can stimulate a temporary increase in demand. This offers a unique opportunity for consumers to be paid for their consumption. Furthermore, in the same vein, the profitability of electricity storage could increase if such events of oversupply recur.

In this extreme situation for the system, market prices play a major role in ensuring the flexibility of the electricity system. This flexibility refers to the system’s ability to adapt quickly to changes in supply and/or demand. More specifically, this means that prices fluctuate to encourage market players to adjust their behavior, either by increasing production when demand is high and renewable supply is low, or by adjusting consumption when renewable supply exceeds demand.

3) Flexibility levers for grid stability

To maintain the stability of the electricity grid, sources of adjustment, or flexibility, are becoming increasingly essential.

Traditionally, gas-fired power plants can adjust their output quickly in response to changes in demand.

Similarly, storage units, such as hydroelectric facilities and certain batteries, provide another source of flexibility by storing energy when supply exceeds demand and releasing it when demand exceeds supply.

The electricity grid itself can contribute to this flexibility through interconnections and exchanges between different countries.

Finally, the ability of demand to respond to fluctuations in supply is a fourth source of flexibility, particularly through demand response. The latter aims to adjust electricity consumption over time to balance the grid, encouraging consumers to reduce their consumption during periods of high demand and shift it to off-peak periods.

Historically, demand response has mainly been provided by large industrial consumers. In France, the NEBEF (Notification d’Échanges de Blocs d’Effacement) is an example of how these players can play an active role in balancing the system, while being remunerated for doing so. This system allows grid users with an adjustment capacity of at least 100 kW to actively participate in demand modulation. By way of comparison, a typical household has an average monthly peak consumption of 4.26 kW. These large consumers, who often face more variable electricity prices, also have greater capacity to adjust their consumption in response to these price fluctuations and are often referred to as « elastic consumers. »

Conclusion

In the context of the transition to an electricity system increasingly based on renewable energies, maintaining the balance between electricity supply and demand represents a major challenge. Thanks to the functioning of the electricity market, new alternatives for flexibility and demand response are emerging to adapt to the availability of renewable energies.

However, to fully exploit the potential of these adjustments, it is essential to actively involve all consumers. A second article (link) explores in more detail the crucial role that residential consumers can play in the flexibility of electricity demand.

[1] The 49.5% share of carbon-based sources in final energy consumption in France is relatively low compared to other European countries. This difference can be explained by the fact that France has already electrified a number of energy uses, such as heating, which reduces the share of fossil fuels in final consumption. In addition, more than 40% of France’s electricity generation capacity is nuclear, a non-carbon but non-renewable energy source. (Source: Breakdown of primary energy consumption by energy source, SDES, France’s energy balance.)

[2] Electricity currently accounts for only a quarter of final energy consumption and is expected to account for 55% in 2050 (Source: RTE).

[3] It is typically low in summer at midday when there is a lot of solar production and little demand, but high in the evening in winter when there is little wind.

[4] In 2023, 45.4% of France’s electricity capacity will come from renewable sources. Of these, 28.4% are non-controllable sources, such as wind and solar. (Source: 2023 Electricity Balance Sheet, RTE.)

[5] Denholm, P., O’Connell, M., Brinkman, G., & Jorgenson, J. (2015).Overgeneration from solar energy in California. A field guide to the duck chart(No. NREL/TP-6A20-65023). National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL), Golden, CO (United States).

[6] In Europe, large-scale hydro storage capacities are already fully exploited, while battery storage, although part of the solutions for making the electricity system more flexible, remains limited to small scale due to capacity and cost constraints. Large-scale, long-term imbalances, sometimes amounting to several gigawatts over several days or even months, remain a challenge for battery storage.

[7] Source: Commission for Electricity and Gas Regulation (CREG).