Abstract :

· Since 2008, Europe has been in a prolonged economic slowdown that has had very uneven effects on employment and unemployment across countries.

· Since the level of growth is not sufficient to explain the differences in unemployment rates between European economies, we will attempt to highlight the importance of other factors that come into play (number of hours worked per person, productivity, inactivity).

· Labor market regulations and the numerous reforms that have been carried out in recent years have also played a major role in employment and unemployment dynamics.

· We will address three major areas of these reforms: flexibility and labor costs, as well as income support for the unemployed.

The onset of the financial crisis plunged the global economy into recession in 2008-2009. The rebound in activity observed in 2010-2011 quickly gave way to a slowdown in growth in most European economies, which have been evolving in a scattered manner since 2012, when the sovereign debt crisis emerged. However, differences in growth are not sufficient to explain the differences in the rise in unemployment rates in Europe, as shown in the chart below. In this article, we will attempt to highlight the dynamics that can complement this explanation and the regulatory context in which they occur.

1. Unemployment and growth: a fragmented Europe

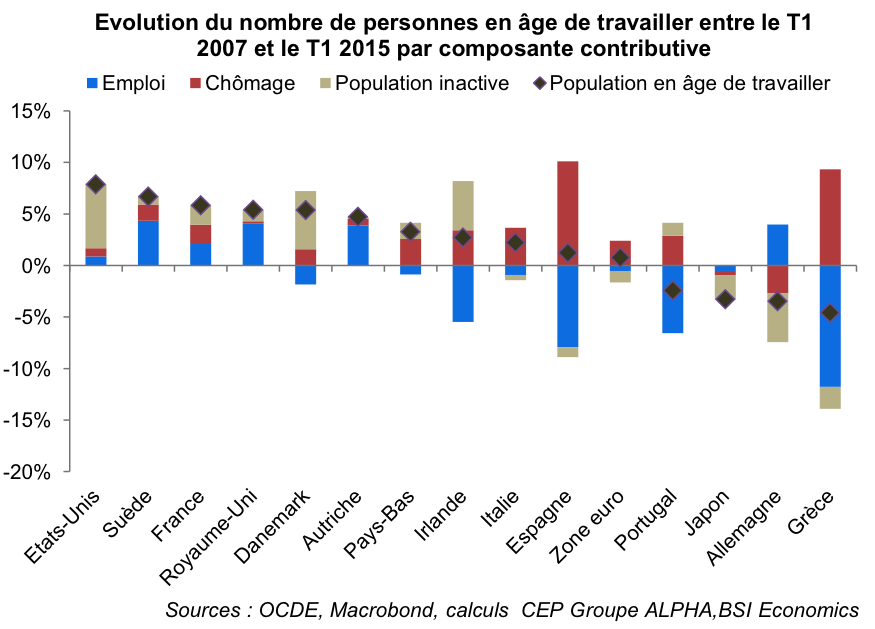

The labor market is directly affected by the economic downturn in Europe on several levels. In the eurozone in particular, the number of people in employment has not yet returned to its pre-crisis level (143 million in Q1 2015, compared with 147 million in Q1 2008), while the unemployment rate remains high (11% in August) despite a slow decline since mid-2013.

Over the period 2008-2015, we can broadly distinguish three groups of countries in terms of economic performance:

· Economies that experienced an acute crisis and saw their activity decline over this period

This group includes Greece, Portugal, and Spain, which faced the consequences of their balance of payments imbalances during the 2000s. It also includes Italy, which has been experiencing a growth slump for several years. All these countries have been swept up in the sovereign debt crisis that has been affecting Europe since 2012. Denmark can be added to this list, as it was already experiencing an economic slowdown before 2008, compounded by the bursting of a real estate bubble and sluggish intra-European trade, which impacted its exports. Ireland is a special case. Faced with a significant drop in activity and an explosion in its public deficits following the collapse of its banking system, the Irish economy has since 2013 returned to a level of growth worthy of its best years.

Weighed down by the impact of the eurozone crisis on their labor markets, the so-called peripheral economies have seen a considerable but uneven rise in unemployment (reaching 26% in Greece in Q2 2015 and 23% in Spain, compared with « only » 12% in Italy). In Denmark, on the other hand, the unemployment rate has remained low (currently at 6%).

· Economies with little or no growth

Although some economies have appeared more resilient than others in recent years, the core eurozone countries (Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Austria) and the United Kingdom have generally seen limited growth between 2008 and 2015. Against a common backdrop of sluggish global demand, some of the drivers of this slowdown are specific to each economy.

Here again, the rise (or fall in the case of Germany) in the unemployment rate has been uneven from one country to another, which their growth differentials do not seem to explain.

· Economies that have not been affected (or only slightly)

In a challenging European environment, some economies, including Sweden, are bucking the trend. The Swedish economy is showing inclusive growth at a higher level than its neighbors, as well as exceptional results in terms of employment.

2. Labor market: dynamics specific to each economy

There are several explanations for this relative disconnect between the level of unemployment and the level of economic growth.

· Number of hours worked per person and labor productivity

The use of labor as a factor of production has an effect on the volume of employment, which is mediated by two factors: the number of hours worked per person and the apparent level of labor productivity. The impact of economic growth on the number of jobs therefore depends on the effects of productivity gains and changes in the number of hours worked per job.

The graph below shows that French growth is exclusively the result of increased productivity, while the quantity of labor used, whether in terms of employment volume or hours per job, makes a marginal contribution.

In the United Kingdom, growth is much more job-rich, but productivity gains are zero. In Germany, the introduction of short-time working has made it possible to maintain productivity at the cost of a reduction in the number of hours worked per person, while the volume of employment has remained relatively dynamic.

Among the so-called peripheral countries, those economies that underwent the most severe adjustment in terms of employment volume benefited from a rebound in productivity and returned to growth (Spain, Ireland, and Portugal to a lesser extent). In Italy, employment has undergone a less severe adjustment in response to the economic downturn since 2008, and the unemployment rate has risen less sharply. However, as the eurozone recovers, Italian growth remains sluggish and economic activity is struggling to exceed its 2000 level. While Italy has seen a smaller decline in employment, this has come at the cost of stagnant (already low) productivity.

· Proportion of inactive people in the working-age population

The impact of changes in the number of jobs on the unemployment rate depends on changes in the size of the labor force, i.e., the number of people who are employed or seeking employment. In several countries, changes in the number of inactive people over the past several years have obscured the relevance of the unemployment rate. This is particularly the case in Denmark, where it has been said that the level of unemployment has been contained despite the country’s difficulties over the last decade. In the United States, the Federal Reserve used the argument of underemployment, among others, to justify keeping its key interest rates at their lowest level in September, even though the unemployment rate is falling and could soon be below 5%.

The demographic profile of an economy is a significant factor in determining the active (unemployed or employed) and inactive components of the working-age population. Overall, economies with dynamic demographics have been more prone to an increase in the proportion of inactive people, which explains the relatively limited rise in the unemployment rate given the decline in the employment rate in some countries. Their inability to absorb the increase in the working-age population is contributing to a rise in inactivity, particularly among new entrants and people nearing the end of their careers.

As mentioned above, in some economies, the scale of the slowdown has been such that macroeconomic conditions have prevailed over other factors (productivity, number of hours worked per person, inactivity) in explaining the rise in the unemployment rate since 2008, which is the result of significant job losses. In Spain, for example, where the number of people of working age has remained relatively stable, the increase in the number of unemployed has been roughly equivalent to the number of jobs lost.

There are therefore several obstacles to understanding the impact of growth on the level of unemployment: the number of hours worked per person, apparent labor productivity, and changes in the size of the labor force. Given these factors, it is important to bear in mind that the significant divergences that have emerged within European economies in recent years are the result of a combination of factors that limit the relevance of a crude comparison of unemployment rates.

3. What reforms and why?

In recent years, the labor market regulations specific to each economy and the reforms carried out in recent years have contributed to the development of the dynamics we have mentioned.

After the implementation of supportive fiscal policies in the first two years of the crisis, the recognition of the structural nature of the crisis in Europe led to a wave of measures affecting all areas of labor market regulation, three major aspects of which we will discuss in this section.

· Labor market flexibility

The dualism that characterizes the labor market in European economies is at the root of a certain concentration of precariousness. This problem is directly linked to the role of fixed-term, apprenticeship, part-time, and other types of contracts as adjustment variables, a phenomenon that excludes the most vulnerable populations from sustainable integration into the labor market. This problem has been addressed in a rather uneven manner in Europe in recent years, as evidenced by the numerous measures to increase labor market flexibility.

In several economies, the reforms undertaken reflect a desire to limit the impact of economic cycles on employment, at the cost of greater flexibility in the number of hours worked per person. Examples include the increased use of short-time working in Germany, the introduction of wage compensation mechanisms in the Netherlands, and the hour bank in Portugal.

In other countries, flexibility measures have focused more on hiring and dismissal conditions. Europe has seen a proliferation of measures aimed at facilitating individual or collective dismissal procedures and the use of fixed-term contracts (zero-hour contracts in the United Kingdom, the Poletti decree in Italy, internships in Spain). This trend toward greater flexibility must be viewed in the context of the economic and political constraints weighing on governments. In Italy, the government is fully aware of the dualism of its labor market. However, the country’s economic situation is forcing policymakers to choose between reducing this phenomenon in the medium term and encouraging hiring in order to revitalize the economy and avoid (as far as possible) long-term mass unemployment.

· Labor costs

Labor costs have played an important role in the development of macroeconomic divergences among eurozone members. The surge in unit costs (index of the cost of a unit of production) in the 2000s led to a deterioration in competitiveness for a whole group of countries, which saw their external accounts rapidly deteriorate. The onset of the eurozone crisis and the explosion of unemployment in these countries coincided with their limited ability to engage their workforce in a competitive production process. In Italy and Greece in particular, the employment rate was already well below the eurozone average in 2007 (59% and 62% respectively among 15-64 year olds at their pre-crisis peak).

In contrast, the countries that have best integrated into European competition, the Netherlands and Germany, as evidenced by the size of their trade surpluses and their openness rates, are those with the highest employment rates in the eurozone (close to 75%). The strong performance of German foreign trade, whose surpluses were until recently based almost exclusively on intra-zone trade, has been largely supported by a policy of wage deflation (as well as the widespread use of atypical contracts).

The reduction in competitiveness gaps and the reconvergence of unit labor cost dynamics have been achieved since 2009 through an adjustment that has been deadly for domestic demand in uncompetitive countries. Against a backdrop of inadequate demand management at the European level, stimulating employment is therefore difficult despite these adjustments. To remedy this, subsidies (Italy, Ireland) and exemptions from social security contributions (Spain, Sweden) have been introduced in order to further reduce the effective cost of labor and boost employment in the short term. In contrast, in Germany, the adoption of a general minimum wage in January 2015 is clearly good news for Europe, as it contributes to the convergence of wage costs and stimulates overall demand.

· Income support for unemployed people

Support for low-income individuals varies from one country to another. These differences can be explained by the heterogeneity of their macroeconomic situations. In countries where the unemployment rate is close to its structural level, convergence towards full employment requires the implementation of measures that will impact the labor supply and the reservation wage of unemployed people. In contrast, in economies in crisis, reducing the number of unemployed people first requires a reconvergence of the actual unemployment rate towards its structural level, and therefore a return to long-term growth rates.

In this respect, the transformation of public employment services addressed in the Europe 2020 strategy seems likely to benefit economies where progress in terms of employment is expected on the labor supply side (Germany, Sweden, and Austria in particular).

Conclusion

The rise in unemployment in Europe is the result of a prolonged slowdown in economic activity, which has been managed in very different ways from one country to another. Added to this is the fact that in each economy, the labor market is subject to its own economic and demographic dynamics. Under these conditions, it is extremely difficult to draw a clear comparative assessment.

However, the Swedish economy, whose inclusive growth has enabled it to achieve an employment rate of close to 80%, is an exception. In all other countries, the rise in the employment rate (Germany, Netherlands, United Kingdom) has come at the cost of reforms that do not address the growing dualism of the labor market.