In their book Race Against the Machine, published in 2011, McAfee and Brynjolfsson predict that around 50% of existing jobs will become potentially automatable by 2030. This statement has given rise to fears of mass unemployment as a result of technological progress.

However, recent articles have put forward a more nuanced perspective. In particular, technologies such as artificial intelligence are not expected to replace entire professions, but rather certain tasks within them (Brynjolfsson, Mitchell, and Rock, 2018). Furthermore, the adoption of new technological tools requires a general reorganization of companies’ internal processes and a redefinition of the roles of their employees. These reorientations are costly and time-consuming, thereby mitigating the risk that the acceleration of technological progress will exceed workers’ ability to adapt.

IT professions are the most exposed to technological progress

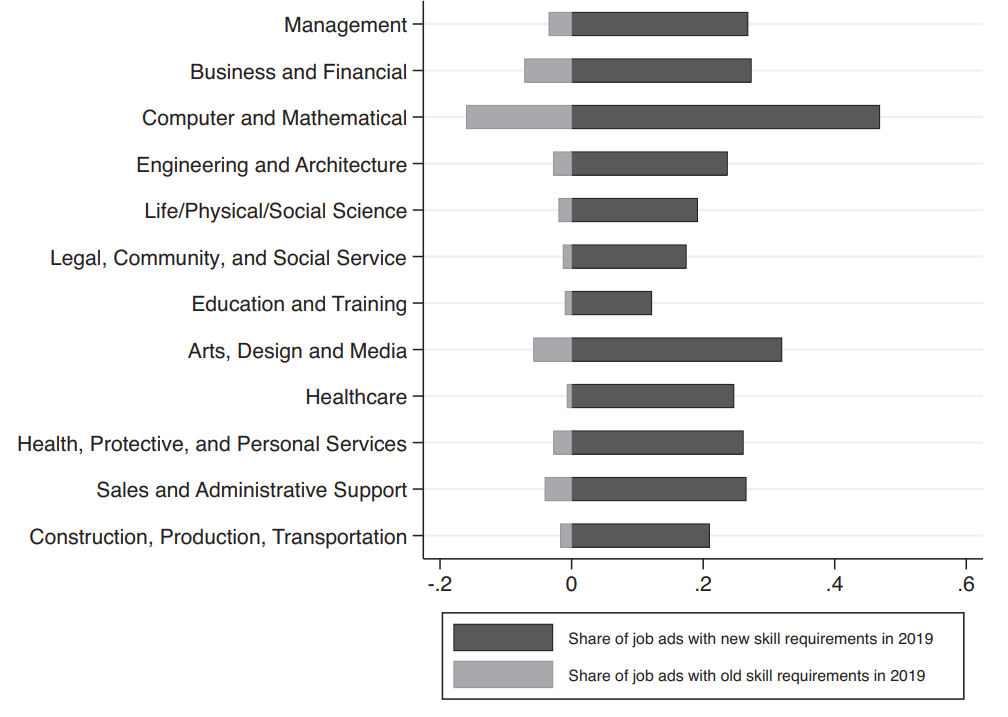

The professions most affected by the digital revolution are those directly related to it. Deming and Noray (2020) find that the skills required in IT job postings are those that have evolved the most between 2010 and 2020. Figure 1, taken from their article, shows that 50% of the skills required in 2019 in IT and mathematics professions did not exist 10 years ago.

Figure 1: Rotation of skill requirements by occupational category

Source: Figure taken from Deming and Noray (2020)

In comparison, more traditional occupations such as school teachers or legal advisors required less than 20% new skills in 2019. According to the authors, this high turnover rate leads to a constant depreciation of human capital, forcing IT professionals to undergo periodic training in order to remain qualified for their jobs.

Similarly, Beaudry, Green, and Sand (2016) describe how demand for highly skilled workers slowed during the first decade of the 2000s. According to them, this is due to the fact that the first wave of computer technologies reached maturity. While many computer scientists were needed during the adoption and dissemination phase of these technologies, this is less the case once the tools are in place. We could expect a similar dynamic to occur with the artificial intelligence (AI) revolution, where the need for coders and data scientists will peak at the time of mass adoption and then decline.

Examples of new and disappearing skills

As an example of a new skill, Brynjolfsson and McElheran (2016) describe how the use of databases for data-driven decision making by managers almost tripled in the US manufacturing industry between 2005 and 2010, reaching 30% of factories by the end of the period. The spread of this practice required the creation of digital tools that summarize information in real time and make it easily accessible. In addition, it required a minimum level of technical and statistical knowledge on the part of managers so that they could use the information collected to make appropriate decisions.

One example of a skill that is disappearing is the ability to code in Flash, a software program used to create online games. In 2010, Steve Jobs announced that Flash would no longer be supported by Apple devices, a decision motivated primarily by strategic rather than technical considerations. As a result, the number of job postings requiring Flash skills saw a sudden and significant decline. Horton, Tambe, and Wharton (2019) describe how, despite the sharp drop in demand, the salary conditions for Flash coders did not deteriorate. This is because far fewer new graduates applied for jobs requiring Flash, and some of the existing Flash coders successfully transitioned to other jobs. This example shows that the disappearance of demand for a given skill does not necessarily have to be accompanied by difficulties for the workers concerned, as long as there are jobs available that require skills that are sufficiently similar to allow for retraining.

Facilitating skills adaptability: a public policy issue

Some recent academic articles downplay the threat posed by technological innovations and emphasize that workers can successfully adapt to changing skill requirements.

Public authorities have a role to play in facilitating this adaptation. In particular, a 2021 OECD report identifies a set of cross-cutting skills that are in high demand across a wide variety of occupations. Some belong to the category of soft skills, such as communication, teamwork, organization, and leadership, while others are more cognitive in nature, such as analytical, problem-solving, and digital skills.

Evidence shows that the return on these cross-cutting skills varies depending on how they are combined with other more technical skills and on the professional roles involved. Employers therefore need help in providing effective lifelong learning for their employees so that they can develop the right combination of cross-cutting and technical skills they need to thrive in a digitalized labor market.

References

Beaudry, P., Green, D. A., & Sand, B. M. (2016). The great reversal in the demand for skill and cognitive tasks. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(S1), S199-S247.

Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2011). Race against the machine: How the digital revolution is accelerating innovation, driving productivity, and irreversibly transforming employment and the economy. Brynjolfsson and McAfee.

Brynjolfsson, E., & McElheran, K. (2016). The rapid adoption of data-driven decision-making. American Economic Review, 106(5), 133-39.

Brynjolfsson, E., Mitchell, T., & Rock, D. (2018, May). What can machines learn, and what does it mean for occupations and the economy?. In AEA Papers and Proceedings (Vol. 108, pp. 43-47).

Deming, D. J., & Noray, K. (2020). Earnings dynamics, changing job skills, and STEM careers. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(4), 1965-2005.

Horton, J. J., Tambe, P., & Wharton, U. P. (2019). The death of a technical skill. Unpublished Manuscript.

OECD (2021), OECD Skills Outlook 2021: Learning for Life, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[1]Although Mr. Jobs claimed that the decision was made for technical reasons, many considered this to be a pretext, and that the real reason for withdrawing support was the desire for greater control over the user experience on Apple devices, particularly the iPhone (see Horton, Tambe, and Wharton, 2019 for an in-depth description of this episode).