Summary:

– Post-crisis criticism of companies is channeled through organizations that issue recommendations on corporate governance regulation.

– A parliamentary mission was launched in early 2013 to engage in constructive reflection on corporate ethics, transparency, and accountability.

– Great importance is attached to the image projected by large companies and the confidence they inspire through the establishment of a High Committee responsible for monitoring the application of the governance code, and the creation of an advisory committee to bring together all stakeholders (managers, shareholders, and employees internally, but also externally NGOs, competitors, customers, etc.).

Since the beginning of the 21st century, corporate governance has been a central concern of our globalized societies, in which companies play an essential role and, above all, take precedence over state regulations in global governance. Indeed, strategic activities on a global scale have made these companies powerful and influential, particularly through their lobbying activities. Furthermore, in times of crisis, the idea that the average salary of a CAC40 company executive can reach €2.25 million is striking given the current stagnant purchasing power of employees. In addition, the short-term concerns of entrepreneurial strategies raise further questions about the future of the industrial and productive sector. The subject is not new, but there is still plenty of debate. Legislative revisions are accumulating, with some progress but no real transformation in the way companies are thought about. This context leads us to question the nature and situation of corporate governance in France, as well as the possible means of reforming and strengthening its effectiveness, legitimacy, and transparency.

First, let us briefly recall the traditional and commonly accepted definition of corporate governance. It refers to the institutional and behavioral mechanisms that apply to corporate executives in the way they structure their activities and decisions. This mode of governance synthesizes the economic, financial, informational, and social concerns of the company.

This theme of corporate decision-making was first explored by Berle and Means in 1932 in The Modern Corporation and Private Property. In this work, they examine the evolution of large corporations and present the separation of ownership and control of the firm as a fundamental principle of modern corporate finance. From then on, the two distinct figures of the shareholder and the corporate executive appeared at the heart of what has been called « the managerial revolution. » These two figures regularly come into conflict, which is studied in the context of what is known as agency theory. Shareholders are the providers of capital and they appoint managers to carry out the financial strategies of the company in question. However, it is often the case that managers, whose main objective is the growth of the company, have interests that diverge from those of shareholders, who seek to maximize the profit on which they receive dividends. The asymmetry of information between these two players in the company can lead to failures in the management of the firm.

Referring to the tradition of John Rogers Commons (1862-1945), who defended the importance of « reasonable capitalism, » recent years have given rise to a daily need and necessity for clarification of corporate management. This involves rethinking how to guide the company and make decisions, refocusing the rules in the face of a proliferation of strategies. The return on capital should not be the sole or dominant goal of the firm. Commons makes a point of articulating economic and legal concerns in order to pursue ethical principles.[1]. The distribution criteria are carefully negotiated and analyzed and could be particularly well put into perspective with the recent period.

Corporate governance and share ownership in France

In France, these normative rules governing corporate operations and life are set out in a governance code. Three bodies are currently responsible for regulating this area in accordance with various recommendations: the European Commission with its action plan on corporate governance and company law, the French Association of Private Enterprises (AFEP) and the Movement of French Enterprises (MEDEF).

In reality, France has two governance codes. The first is the AFEP-MEDEF code, which is dedicated to large CAC40 companies. The second, the Middlenext code, is tailored to small and medium-sized enterprises, their size, capital structure, and history. It offers all SMEs recommendations for managing and evaluating their business activities.

Shareholder distribution:

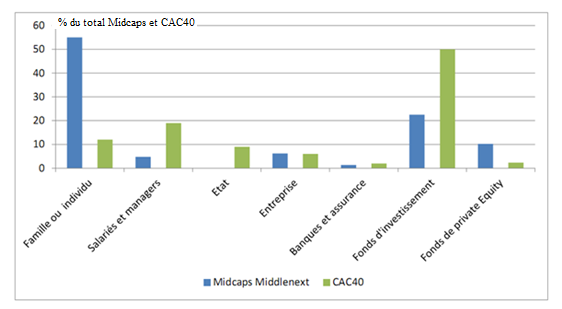

Sources: IFGE, MiddleNext Research Institute, BSI Economics

As can be seen in this graph, the capital structure of companies, which is key to determining governance arrangements, is predominantly family-owned for Middlenext companies, whereas it is mainly made up of investment funds for CAC40 companies.

In a context of financialization, the ultimate goal of each of these companies differs, ranging from maximizing shareholder value to ensuring the long-term sustainability of the company. Investment funds aim to achieve high returns, while family structures are more focused on profitable growth and generational continuity. There is therefore a governance model specific to France and, more generally, to Europe, with more concentrated company ownership, which is conducive to better monitoring.

However, even though CAC40 companies have a more dispersed capital structure, there is also a significant proportion of family shareholding. Nevertheless, companies with dispersed capital are not absent, even though French regulations are not the most advantageous. The values promoted by company managers determine the very structure of the company and therefore its governance. These values are subjective and vary from one person to another. This is why we now consider the analysis of governance through its technical aspects to be the only feasible approach; governance that seeks to protect the interests of financial investors, to involve the various stakeholders more closely, to distribute flows within the company more equitably, etc.

Thus, the nature and position of the company’s CEO varies depending on its size. In 75% of cases, the CEO of a medium-sized company is the largest shareholder, compared with only 36% of the largest listed companies. However, the challenge of governance lies in the fact that performance requirements and risk limitation are closely correlated with executive compensation. Indeed, it is considered obvious that involvement should be remunerated on the basis of the company’s results. However, since 2013, an « innovative » study by the Strasbourg School of Management has emerged, explaining that contrary to what one might think, there is no evidence that executive salaries are indexed to the performance of the companies they run. Furthermore, they highlight the fact that the creation of a Compensation Committee would have the opposite effect, namely increasing executive salaries. Finally, the presence of independent directors on the board of directors would not moderate executive salaries. However, no study can corroborate this analysis, and it is more commonly accepted that compensation and stock options are distributed taking into account the general interest, market practices, and the performance of the CEO, the rules for which were set at the beginning of the fiscal year.

In France, we see that the one-tier management structure (with a board of directors led by the Chairman, who may also serve as Chief Executive Officer (CEO)) is adopted in 75% of cases, while only 25% of companies have a supervisory board and a management board.[2]. Companies have been free to choose between these two forms since 2001 in France. It turns out that each model has its own advantages and disadvantages, and it is generally accepted that there is no one-size-fits-all answer to the question. It is necessary to look at both the form of the company and the principles governing it, which vary from country to country.

It appears that the main reason for the limited development of the dualistic form in France can be explained by the fear of losing dominant influence in small family-type companies. Indeed, this model is based on the division of executive power between a management board (including the Chairman) and a supervisory board to which the management board is accountable. Management and control are therefore separated. In the latter case, the management board holds all the power within the company and must therefore be subject to supervision, which involves more formalities and rigidity, as everything must be regulated, including information flows. In public limited companies, the director must be independent and autonomous, but cannot be fully independent and carry out their duties if they do not have the necessary information.

Historically, it was the financial markets that highlighted the importance of separating powers to strengthen corporate control, even if this happened relatively late in France. The challenge of corporate control is to change the distribution of flows between stakeholders. This can give rise to potential conflicts that could undermine the overall functioning of the company.

The adoption of either of these forms remains at the discretion of the company, with no privileges granted under the codification. Thus, no structure is imposed, but it is monitored and codified by the AFEP and MEDEF authorities through the preparation of annual reports.[3].

The possibility of « good » governance that is clear and effective?

The constant quest for « good governance » appears to be a key objective. This holy grail manifests itself through the issue of transparency, which can be considered the ethical consequence of governance. Companies are obliged to disclose certain information about their operations, to honor their contractual commitments, to guarantee the quality of their services or products, etc.

The question is: which of these codes are actually in force and what objectives do these rules seek to achieve? The interests of shareholders? Those of other stakeholders? And what adverse effects does codification have in return? This desire for transparency and accountability arises at a time when actors are losing legitimacy and the fight against corruption is intensifying, but also in a context of globalization that requires adaptability, credibility, and corporate culture as determinants of a company’s competitiveness. The question under debate is actually very basic, as it revolves around « Who owns the company? And how can the company be effective depending on the distribution of ownership? »

Two major issues can be identified in the debate that was reopened in 2013. The first concerns the role to be given to employees, managers, and shareholders in the functioning of corporate governance. The second concerns the establishment of a regulatory environment that allows both the level of investment in companies and the French industrial fabric to be maintained in order to avoid job losses and deindustrialization.

In the previous section, we highlighted a dual internal dynamic, with diverging interests between the opaque business world (led by executives) and the transparency sought by shareholders and employees, the two stakeholders in the company. This has given rise to a three-way debate between transparency, legitimacy, and trust among stakeholders.

Transparency—which today permeates every area of society—in terms of corporate governance refers to concerns about the legitimacy deficit of corporate management. It is an attribute of market efficiency and a symbol of the moralization of the rules of business life. By making a company’s organizational chart more transparent, its internal and external relationships should be easily analyzable and understandable, which should restore the company’s reputation and therefore its legitimacy. However, this debate is not without its adverse effects and questions about ownership among the various players in the company. The European Commission is therefore keen to open this dialogue, with an increased focus on transparency intended to ensure the smooth functioning of the decision-making process, empower shareholders, and protect managers.

However, we must not forget to take a critical view of this sometimes illusory goal of transparency, as it does not solve all governance problems and, above all, raises other equally important issues. This requirement for transparency appears essential for effective control. However, this concept can easily be manipulated within the corporate structure, with a few well-informed agents nullifying its expected ethical effects. This is all the more difficult when we consider a reversal of the managerial revolution, with shareholders regaining power at the expense of executives (managers).

Transparency means simplified access to information for shareholders, which further strengthens their superior hierarchical position. However, as we have seen, shareholders have more financial than productive objectives, which can run counter to the interests of managers but also, and above all, to the general interest in pursuing industrial objectives and maintaining the productive fabric.

In line with this European approach to social cohesion within companies, a bill has been drafted in France on the regulation of remuneration practices and the modernization of corporate governance. The aim is to restrict the salaries of executives (which must be approved by shareholders) and ensure that they remain reasonable in relation to those of employees. Shareholders’ ability to exercise control is legitimized by the « transparent » ownership of shares. And it is true that, as a central element of corporate governance, it was necessary to set up an advisory compensation committee.

An update on the reforms

Our political leaders make recurring announcements, leading to regulations on changes in how companies operate, the consideration of different stakeholders, and the assessment of these new laws.[5]Back in 2010, Christine Lagarde was already considering the need for an observatory for listed SMEs, while at the same time Alternext, a European platform, was relaxing the listing requirements on its regulated market. This concern for governance, revived in the wake of the financial excesses of recent years, is such a topical issue that it was the subject of parliamentary debate in the first half of 2013, leading to an information mission by the National Assembly and a report by the AMF.[6]. These round tables, which first appeared in the 2000s, seek solutions to the criticisms levelled at companies, namely the inadequacy of monitoring mechanisms and the rigidity of salary policies[7]. When the report was submitted, the National Assembly specified the three objectives that motivated this fact-finding mission:

» First, to establish a better balance between the law and governance codes, in particular by creating an obligation for large companies to refer to a code; Secondly, to establish stable governance that is open to the company’s various stakeholders : by granting double voting rights to long-term shareholders, by strengthening control over regulated agreements, and by introducing mandatory employee representation on boards of directors or supervisory boards; Finally, promote responsible governance in support of long-term strategies : by creating a class action procedure accompanied by more effective financial penalties in cases of mismanagement; by strengthening the voting power of the shareholders’ meeting in controlling executive compensation policy; by reforming the stock option and free share schemes to restore them to their original purpose; by prohibiting compensation in the form of « top-up pensions. »

All of these proposals should promote a change in culture and a moralization of practices.« [8]

It is therefore up to the public authorities to act as arbiters in order to restore a healthy dynamic to this governance. This is why, among the challenges of these various French reforms, it is necessary to provide guidelines and, in particular, recommendations on executive compensation policy. Such compensation must be determined by the board or a committee in order to adhere to the values of transparency and consistency. Ethics are therefore essential, both internally in terms of reducing inequalities in remuneration and treatment of employees, and in the company’s relationship with its environment. However, in April 2013, the European Commission considered that a change should be made, particularly with a view to developing and publicizing what is now known as CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility).

This latest update to the governance code strengthens legislation in the form of twenty proposals, the substance of which we will attempt to summarize here. Stakeholders, including employees, must play an increasingly important role in decision-making and in the running of their companies. This is why the following is required:

- the establishment of an independent High Committee for Corporate Governance to monitor the principles of the code adopted by the company (diversity within boards of directors necessary for representativeness, separation of the roles of chairman and chief executive officer), interpret the provisions, and make the necessary updates. This is an ethics committee parallel to the CEO, composed of the chairman of the board of directors, three business leaders (Valeo, Pierre et Vacances, Michelin) and three qualified individuals in law and finance.

- An internal consultative vote on the compensation of corporate officers[9]as part of the financial year and a limitation on their term of office;

- more transparent compensation in terms of how it is allocated, justified, and calculated;

- increased transparency in the appointment of directors and their compensation.

The main advances in this new revision aim to monitor the application of the governance code, deepen the principle of consultation, and strengthen the framework for compensation (particularly stock options).

This awareness and desire for improvement are linked to the fact that companies are currently under no obligation to adhere to the governance code and, above all, are not required to explain their reasons for refusing to do so. In February 2013, the commission and the AMF had already expressed their intention to impose sanctions in the event of refusal to adhere. The aim is to clarify issues that are brought up for discussion during general meetings (which are held within six months of the end of the financial year, i.e., between January 1 and June 30).

Conclusion

Corporate news in 2013 and 2014 echoes this desire for change in legislation and corporate law, which is already quite extensive in France, and in the relevance of internal structures. The parliamentary mission focused on the issue of corporate credibility because its impact is not only internal but also affects the health of the economy as a whole. The search for stable but open governance is therefore essential from a European integration perspective.

However, it is worth noting that this quest for transparency in business has historically been associated with industrial and financial scandals (see the Enron-Andersen and Worldcom cases in 2002). It is always in this context that « good » governance practices are questioned. The trend in 2014 at general meetings appears to have focused on « say on pay. »[10], i.e., the advisory vote of shareholders to prove the effectiveness of the committee, as the European Commission seeks to establish a ratio linking the average salary to that of the company director in order to harmonize the remuneration policy of some 10,000 companies in the Union.

Other issues will be raised in the coming months with regard to corporate structure, such as the relationship with quotas for women, foreigners, etc. But, as Michel Prada, former chairman of the AMF, points out, we must be wary of « regulatory fatigue. »

References:

– « Panorama des pratiques de gouvernance des sociétés cotées française » (Overview of governance practices in French listed companies), Ernst & Young et Associés, 2013.

– « Corporate governance structure: decision-making criteria, » IFA, January 2013.

– « Report of the fact-finding mission on transparency in the governance of large companies, » National Assembly, February 20, 2013, No. 737: http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/14/rap-info/i0737.asp

– « Report on companies referring to the Middlenext governance code for the 2011 financial year, » French Institute of Corporate Governance, April 2013.

– « 20 years of dividend distribution in France 1992-2011, » IFGE, May 2013.

– « Corporate Governance Code for Listed Companies, » AFEP-MEDEF, June 2013.

– « 2013 AMF Report on Corporate Governance and Executive Compensation, » October 2013.

– « Corporate governance: what lies behind the talk of transparency? », research paper, Orléans Institute of Business Administration, Dominique Bessire, 2003.

Note:

[1] Ethics means that managers have concerns that go beyond maximizing shareholder returns, including a number of responsibilities towards stakeholders, environmental considerations, respect for individual rights, etc. Ethics therefore applies to the various spheres in which the company operates.

[2] This dualistic form comes from the German model and, as in Germany, was only introduced in France on an optional basis (from 1966 in France).

[3] Other players are involved in corporate governance regulation, including: the AFGE (French Corporate Governance Association), the AMF (Financial Markets Authority), the AMRE (Corporate Risk and Insurance Management Association), and the European Confederation of Directors’ Associations. It should be noted, however, that the governance model adopted does not determine the decision-making process.

[4] Interested readers may wish to consult the implications of the 2005 white paper.

[5] These issues are addressed in the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (2002) in the United States and the LSF, the French Financial Security Act (2003).

[6] Publication by the French Financial Markets Authority in October 2013, 10th annual report on corporate governance and executive compensation in listed companies. This is an overview of corporate practices at 60 companies following the Afep-Medef guidelines.

[7] Notably with incomplete indexation of salaries to inflation.

[8] Presentation of the fact-finding mission on transparency in the governance of large companies, online: http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/14/controle/lois/transparence.asp

[9] Legal entity at the head of a company.

[10] Interested readers may consult Say on Pay International Comparisons and Best Practices by the French Institute of Directors (IFA), November 2013.