- The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) was launched in October 2023 in the European Union (EU) and will come into full effect in 2026. While the CBAM inevitably addresses the issue of « carbon leakage, » several studies show that it only partially resolves the problems of loss of export competitiveness and could even generate undesirable externalities.

- This second article looks at the « inward processing » customs regime, which provides an advantage for industries in countries that re-export products initially subject to the MACF and then processed before being exported outside the EU. The regime would have both direct and indirect impacts.

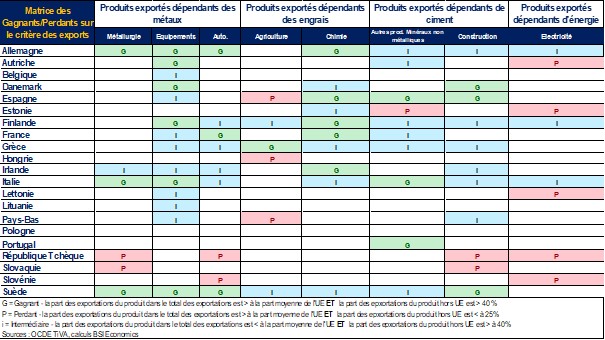

- Direct impacts: industries that depend on MACF products but export a significant proportion of their products outside the EU would be among the potential « winners. » This is particularly the case for Germany, Italy, and Sweden (metallurgy, capital goods, automobiles), France (automobiles, chemicals), and Spain (construction, other non-metallic mineral products, chemicals). Among the « losers, » the countries that stand out most often are the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

- Indirect impacts: the « inward processing » regime would encourage certain industries to reduce their procurement of carbon-intensive products on the European market. This would weaken European industries that supply these industries seeking inputs from outside the EU. The main « losers » include Belgium, the Czech Republic, Slovenia and, to a lesser extent, the Netherlands, Lithuania and Austria.

Since October 2023, the European Union (EU) has had a new tool in its quest for decarbonization: theCarbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). The adoption of this regulation, which will come into full effect in 2026, complements previous measures taken by the EU, such as the introduction of acarbon market andthe phasing out of free pollution permits, with the aim of combating « carbon leakage.«

An initial article published on the BSI Economics website identified the EU countries with the highest costs associated with the CBAM, due to high non-EU imports of products subject to the CBAM. This analysis showed that the system could prove to be even more costly for countries with high levels of imports of non-EU metal products and relatively higher carbon intensity.

This second article revisits a point raised in aBpifrance study[3]concerning the existence of the « inward processing »customs regime, which promotes the price competitiveness of industries during re-export operations. This regime allows customs duties and taxes to be suspended for industries that re-export products outside the EU for which they have generated added value based on imports of intermediate goods. However, it should be noted here that « inward processing » is not intended to fully offset the impact of the MACF, but rather to mitigate its effects for eligible industries.

The existence of this regime would allow several countries to partially offset the costs associated with the MACF. On the other hand, it would penalize certain countries due to a potential reorganization of trade in MACF-related products. This note seeks to distinguish the winners and potential losers of the MACF through the lens of this regime and its impact.

Who are the winners/losers of the MACF linked to the direct effects of « inward processing »?

Due to the existence of the « inward processing » regime, certain industries will have the opportunity to rely on their export markets outside the EU to reduce the bill associated with the MACF. The MACF would therefore have the direct effect of strengthening the competitiveness of certain countries’ industries outside the EU.

The first step is to use the technical input coefficients(TICs) provided byEurostat to identify the countries and industries that benefit most from such a scheme. These coefficients make it possible to determine which products are most dependent on products subject to the MACF. The higher the coefficient, the greater the level of dependence. It is these same industries whose export performance outside the EU, by country, will need to be isolated.

The logic behind this cross-checking is as follows: i) the more an industry makes intensive use of intermediate goods, the import of which is subject to the MACF, and ii) the more this industry exports a significant proportion of its products outside the EU, the more it could expect to see a reduction in its MACF-related costs. Conversely, industries that export most of their products within the EU would not be able to benefit from the « inward processing » regime and would therefore pay the MACF at the full rate.

The industries with the highest CETs by product type are:

- Metallurgical and metal products, machinery and equipment, and motor vehicles, compared to imports of steel and aluminum (metallurgical products category).

- Agriculture and chemicals[7], compared to imports of nitrogen fertilizers (broad category of chemicals).

- Construction materials and other non-metallic mineral products, compared to imports of cement (broad category of other non-metallic mineral products).

- Electricity, compared to imports of energy, hydrogen, and electricity (broad category of electricity, water, gas).

The second step is to calculate the export performance of industries with the highest CETs. To do this, two metrics are used:

- The share of non-EU exports in total exports of the product concerned. The higher this share, the more a country’s industry will be able to rely on the « inward processing » regime to avoid the MACF when importing intermediate goods subject to carbon pricing.

- The weight of these exports in total exports, all products combined. The purpose of this indicator is to observe whether the products in question represent a significant share of the country’s exports, in which case the gain from the « inward processing » regime will be substantial.

All results by country and product can be found in the table below (full details are available in the appendix). A green cell « G » means that a given country for a given product is a « winner, » a red cell « P » means a loser, and a blue cell « i » means an intermediate case (when a country exports a relatively high share outside the EU but this represents a relatively small share of its exports).

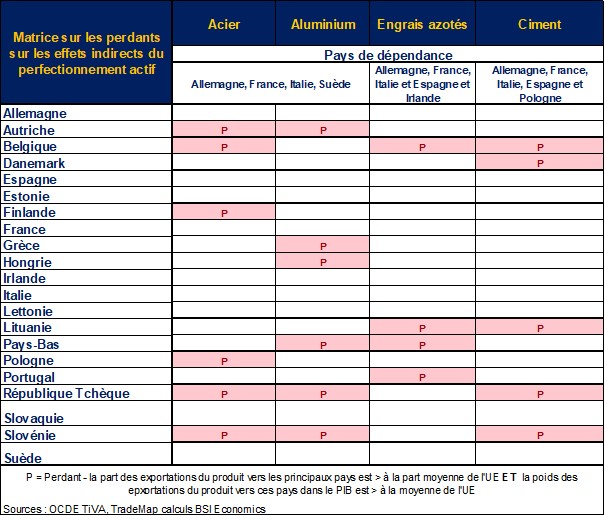

Who are the winners/losers of the MACF linked to the indirect effects of « inward processing »?

The existence of the « inward processing » regime could lead to a reorganization of trade in goods subject to the MACF within the European Union.

Indeed, European industries seem to be « logically » encouraged by the « inward processing » regime to import fewer high-carbon products from their European partners. It is becoming relatively more profitable for certain industries to import high-carbon products from outside the EU, because if they subsequently manage to export outside the EU under the « inward processing » regime, they will be able to reduce part of the cost associated with the MACF. However, if these same products were imported into the EU, they would be subject to full carbon pricing linked to the European carbon market, and no cost deduction would be made. It therefore appears that the mechanism implies a loss of competitiveness for European products, which are also subject to the MACF. Given this observation, substituting carbon-intensive European products with non-European products is clearly of interest to certain industries, which would run counter to the initial mechanism.

This would result in a decline in demand from European industries benefiting from the positive effects of « inward processing. » This decline would be detrimental to the main European countries exporting products subject to the MACF. To assess who would be the « losers » in this scenario, we need to refer to the results of the previous section. The industries in countries that are among the export « winners » due to the direct effects of « inward processing » are those that are likely to have the greatest interest in reducing their European imports of carbon-intensive goods. As a result, their main European suppliers would see a decline in their European market opportunities, which would be all the more significant if they are highly dependent on exports to the « winning » countries due to the direct effects of « inward processing » and if their exports to these countries account for a significant percentage of GDP.

These have already been identified by product in the previous section (see table of winners/losers based on export criteria):

- Steel and aluminum: Germany, France, Italy, and Sweden emerge as the main export « winners » in the metallurgy, capital goods, and automotive industries.

- Nitrogen fertilizers: Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and Ireland emerge as the main export « winners » in the chemical and agricultural industries.

- Cement: Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and Poland emerge as the main « winners » in exports in the construction and other non-metallic mineral products industries.

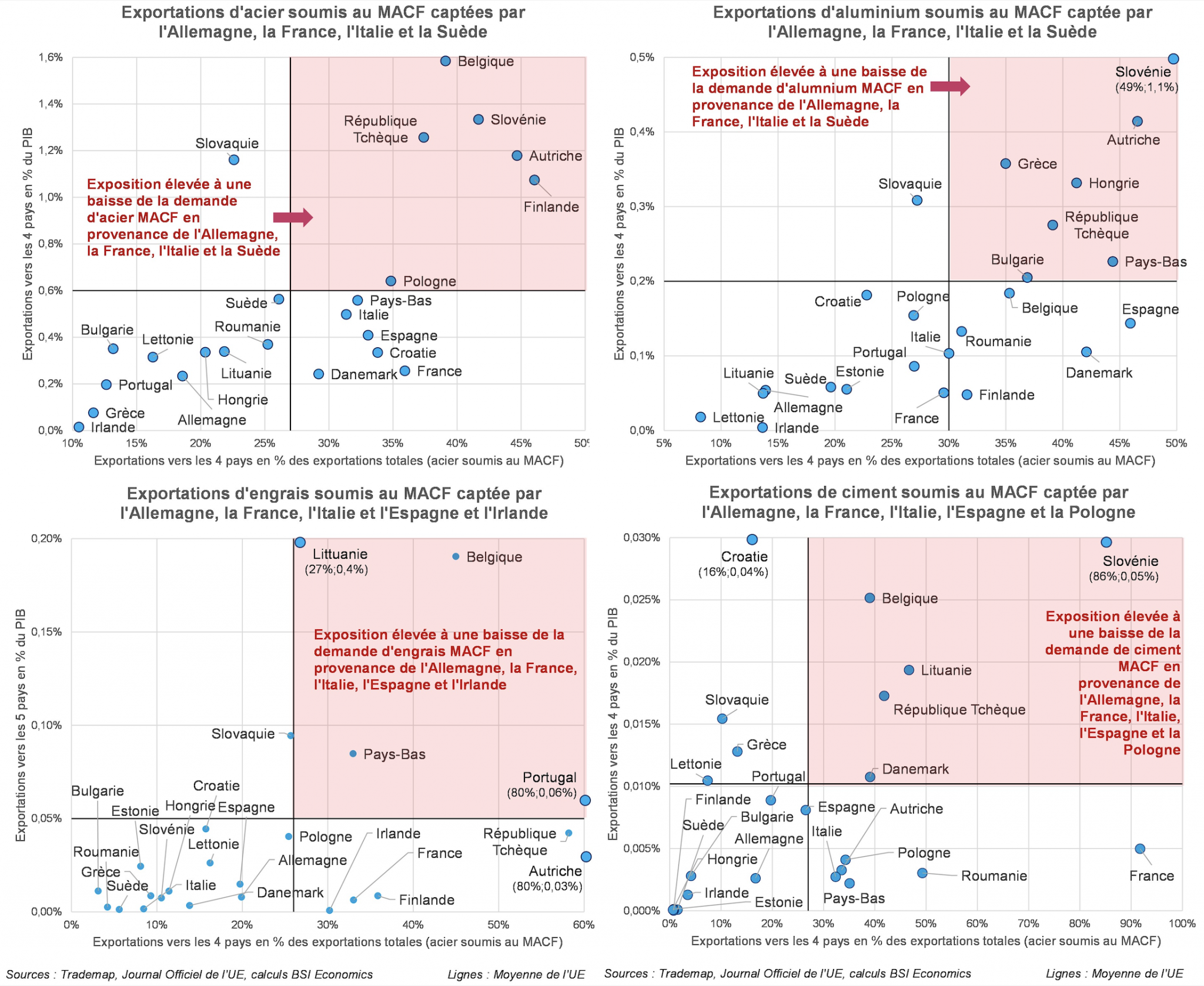

The countries that stand out as « losers » from the indirect effects of the « inward processing » regime are Belgium, the Czech Republic, and Slovenia for three products, and Austria, Lithuania, and the Netherlands for two products. These results are summarized in the table below (and more details are available in the graphs in Appendix 2):

The MACF combined with the « inward processing » regime offers results that defy the initial logic that the mechanism strengthens the competitiveness of European industries. Industries in some countries seem to benefit from it, but these gains are often made at the expense of European partner countries. Those who are « losers » on the EU side are also likely to be « winners » outside the European Union. This aspect is addressed in a third and final article to complete this analysis of the potential « winners » and « losers » of the MACF.

Appendix1

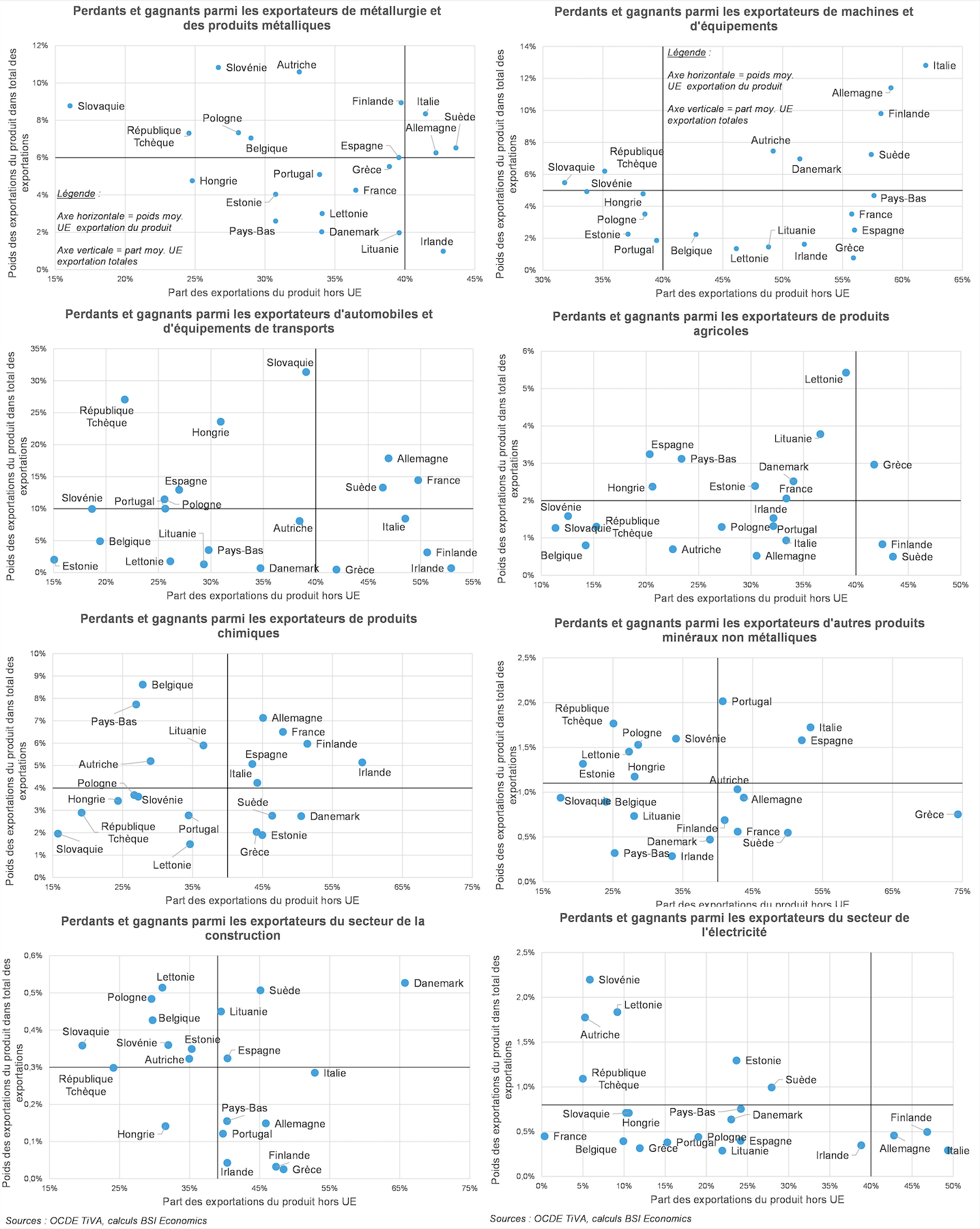

The following eight graphs show the positioning of EU countries for each product. How to interpret these graphs:

- They are based on two criteria: the share of non-EU exports in their total exports for the product concerned (on the x-axis) and the weight of these exports in their total exports, all products combined (on the y-axis).

- The black lines on the axes represent the average for EU countries on the two criteria mentioned in the previous point.

- The countries in the upper right quadrants appear to be the « winners » of the MACF for a given product: they export a significant share of it outside the EU and can therefore benefit from the « inward processing » regime and thus be exempt from carbon pricing for imported intermediate goods subject to the MACF. In addition, exports of these products account for a high proportion of their total exports, amplifying the effect on competitiveness gains.

- The higher a country is located in the upper left corner of the graph, the greater the share of its total exports represented by exports of the product in question. However, its export markets for this product are mainly in the EU. As a result, its ability to benefit from the « inward processing » regime appears limited and it will incur high MACF costs, making it a relative « loser. »

Appendix 2

The following four graphs show the positioning of EU countries for each of the products and countries listed. How to interpret these graphs:

- They are based on two criteria: the share of exports of a product to the main target countries (« winners of the direct effects of « inward processing ») in total exports of that product worldwide (on the x-axis) and the weight of exports of the product to these main countries in the GDP of each country (on the y-axis).

- The black lines on the axes represent the EU average for the two criteria mentioned in the previous point.

- The countries in the upper right quadrants appear to be « losers » because they potentially suffer the highest degree of indirect effect from the MACF with the « inward processing » regime for a given product: they export a higher share than the European Union average to the main target countries, indicating a high level of dependence. Furthermore, if exports of this product to these countries calculated as a percentage of GDP are higher than the EU average, then the impact is potentially high in the event of a decline in demand for this product by the target countries.

[1]For more information on this subject, see the sections on the evolution of theETS Directive.

[2]This phenomenon of leakage consists of relocating the industries that emit the most greenhouse gases outside the EU so that these industries do not have to bear the costs associated with the new environmental standards.

[3] »The loss of export competitiveness would nevertheless be limited for downstream activities that export a processed product based on inputs covered by the MACF to a country outside the EU. In this case, the input can be imported under the inward processing customs procedure, exempting the importer from the MACF. However, this procedure has limitations (the product must be re-exported outside the EU, incentives to purchase inputs outside the EU), » T. Laboureau, Bpifrance (2023). For more information on this subject, seethe interview with T. Laboureau.

[4] It should be noted that benefiting from this scheme is not automatic and involves strict administrative procedures.

[5] Ratio of intermediate consumption of products to market production in a given industry

[6] As a reminder: steel, aluminum, nitrogen fertilizers, cement, electricity, hydrogen, see previous article.

[7] Nitrogen fertilizers are used in particular in the chemical industry for the manufacture of ammonia, nitric acid, pharmaceuticals, dyes, and explosives.

[8]The thresholds are described in the note below the table. For the share of exports of the product outside the EU, the 40% threshold was not chosen arbitrarily but refers to the average share of total EU exports outside the EU, based on OECD data between 2015 and 2020. Similarly, the 25% threshold corresponds to the lowest share of total exports outside the EU over the same period (in this case, the share of the Czech Republic).

[9]There is potentially another indirect effect linked to the fact that the « inward processing » regime combined with the MACF could lead some companies to seek outlets outside the EU and thus reduce their supply of products on the EU market. By doing so, these companies could maximize the potential for reducing MACF-related costs. On the other hand, their « usual » European customers would be forced to source their supplies elsewhere, particularly outside the EU. However, sourcing supplies outside the EU entails potentially higher MACF-related costs. In the case of imports of products subject to the MACF, this cost could even be significant given the carbon intensity of these imports from outside the EU (see previous article).

[10]To facilitate calculations, only countries with a significant weight (greater than 5%) in total EU exports outside the EU for the goods studied were included. The selected countries account for an average of more than 70% of EU exports outside the EU over the period 2018-2022 for the products concerned, which is a very significant share.