- The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) was launched in October 2023 in the European Union (EU) and will come into full effect in 2026. While the CBAM inevitably addresses the issue of « carbon leakage, » several studies show that it only partially resolves the problems of loss of export competitiveness and could even generate undesirable externalities.

- A previous article noted that despite the carbon pricing of the MACF, some EU countries would have an interest in increasing their imports from outside the EU of products covered by this mechanism. This third article examines the potential of countries outside the European Union that appear to have a role to play in responding to a potential increase in demand from the EU.

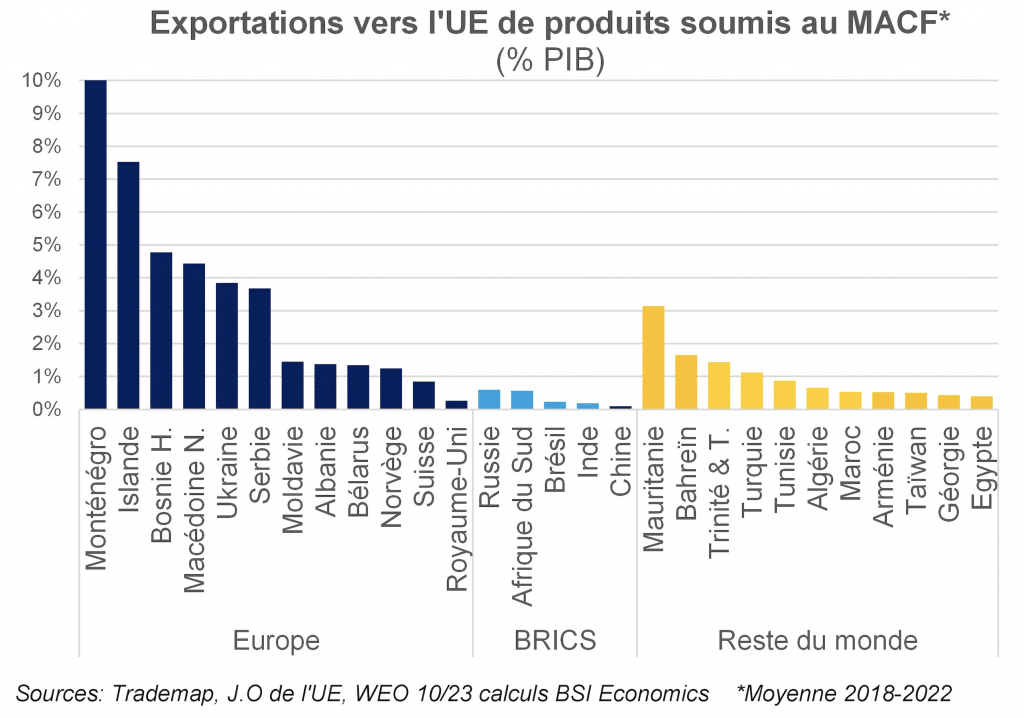

- Exports of products subject to the MACF to the EU from other European countries represent a higher percentage of their GDP than those from countries in the rest of the world. This is particularly the case in Montenegro and Iceland, two countries that could benefit from increased demand from EU countries.

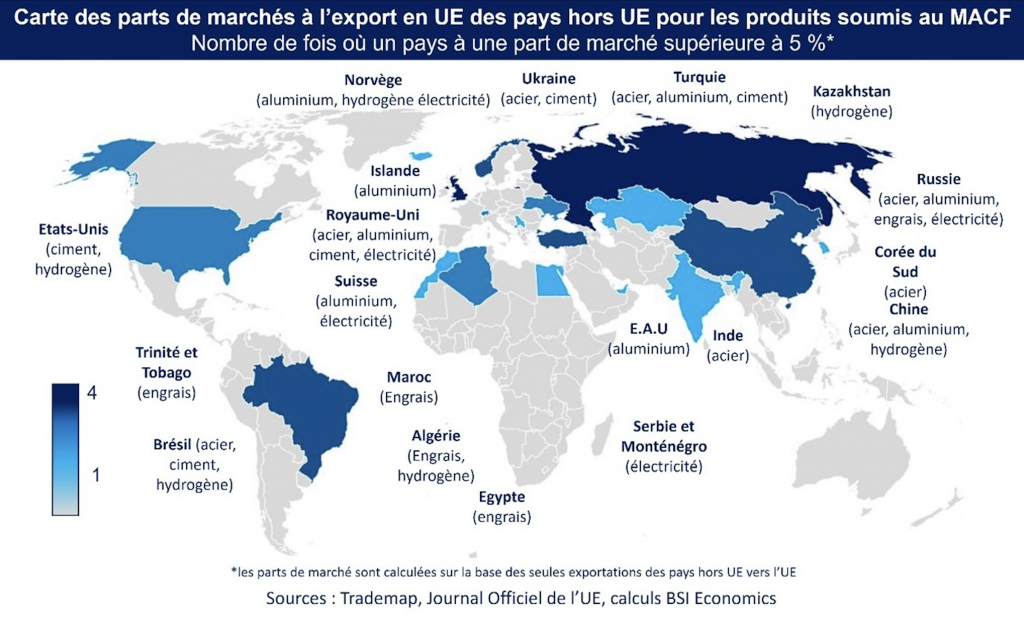

- In terms of market share and potential capture of increased EU demand, the main « winners » would be Russia, the United Kingdom, China, Norway, Turkey, and Brazil.

- Low carbon intensity of exports to the EU would offer a comparative advantage to several countries depending on the type of products exported. Turkey, Brazil, the United Kingdom, and the United States are countries that generally export large volumes of goods to the EU with relatively lower carbon intensity.

Since October 2023, the European Union (EU) has had a new tool in its quest for decarbonization: theCarbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). The adoption of this regulation, which will come into full effect in 2026, complements previous measures taken by the EU, such as the introduction of acarbon market andthe phasing out of free pollution permits, with the aim of combating « carbon leakage .«

The first two articles, published on the BSI Economics website (1 & 2), focused on the potential « winners » and « losers » of the CBAM within the EU. One of the findings of these analyses is that some of the « winning » countries would, in certain specific cases, benefit from replacing their European imports of carbon-intensive goods with imports from outside the EU. Based on this assumption, demand for goods from countries outside the EU should automatically increase, offering export opportunities for countries outside the EU.

This third and final article in this series on the MACF looks at these countries and examines whether any of them stand out, in terms of which products and what climate-related advantages they offer.

Who are the main suppliers of MACF-regulated products outside the European Union?

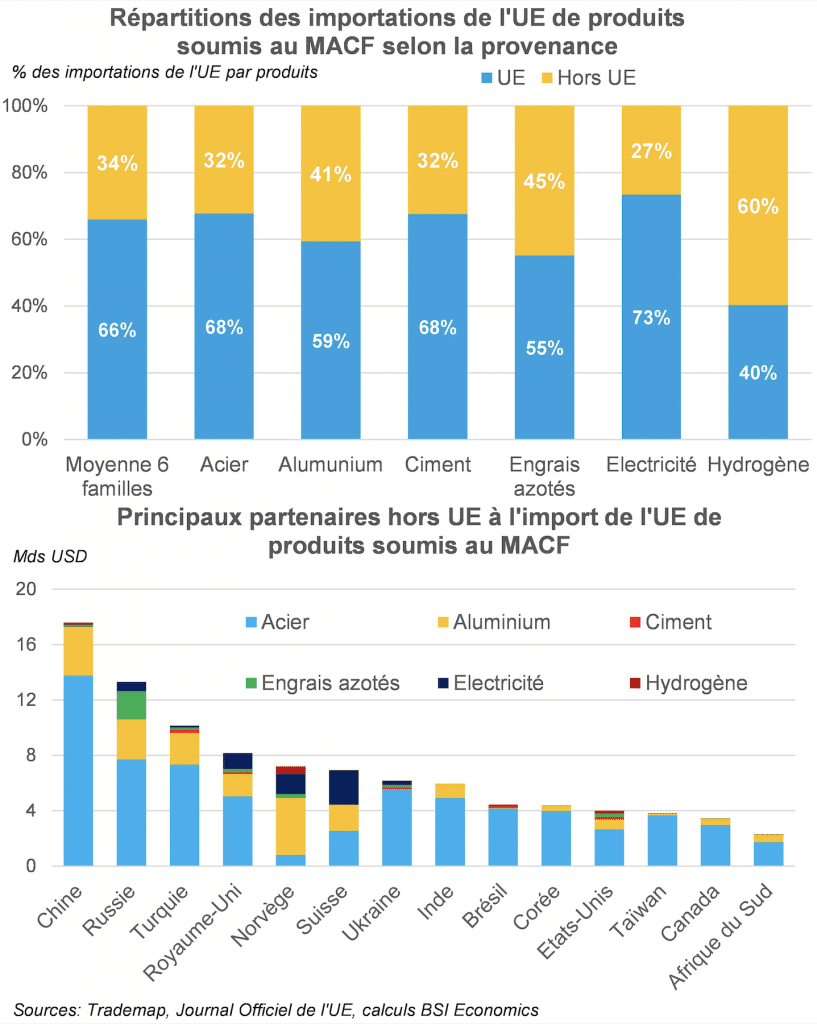

The products covered by the MACF[3]are mainly imported into the EU: 66% on average over the period 2018-2022. While there is some heterogeneity between products (see chart below), one stands out: hydrogen, which is mainly imported from outside the EU (60%).

Among the countries that export these products to the European Union, it comes as no surprise that China is the leading supplier of products subject to the MACF (see graph above). 98% of Chinese imports subject to the MACF are steel and aluminum. Apart from Norway, the main suppliers of products subject to the MACF export mainly metallurgical goods, especially steel. This is particularly the case in emerging economies (Turkey, Ukraine, India, Brazil, South Africa). The cases of European countries that do not belong to the EU (the United Kingdom, Norway, and Switzerland) show that, unlike other countries in the world, they export a significant share of energy, whether electricity or hydrogen. Russia also stands out for its exports of nitrogen fertilizers (15.3% of its exports of products subject to the MACF to the EU).

Who are the potential winners of the MACF among non-EU countries?

To identify the potential « winners » of the MACF among non-EU countries, three criteria are used here:

- The share of GDP accounted for by exports to the EU of products subject to the MACF. The higher this share, the greater the gain for a country from an increase in EU demand for these products, regardless of its other parameters.

- The market shares of countries that export products subject to the MACF to the European Union. Countries with the highest market shares are, in principle, in a more favorable market position to respond to an increase in EU demand. They can then leverage their competitiveness to try to gain market share from their EU competitors.

- The carbon intensity of exports to the EU for product categories subject to the MACF. The « winning » countries within the EU, which have an interest in sourcing outside the Union’s borders, will not be able to fully offset the total cost of the MACF by importing from outside the EU. It will therefore be in their interest to source from countries whose products have the lowest carbon intensity. As a result, countries with low-carbon products appear to have an additional advantage in the event of increased demand from certain EU countries.

Criterion 1 –Exports as a percentage of GDP

Given their geographical proximity to the EU, European countries are those for which exports to the EU of products subject to the MACF are highest as a percentage of their GDP (see chart below). Although the United Kingdom, Norway, and Switzerland are the EU’s leading partners for these products (see previous section), the size of their GDP means that the ratio observed is low (0.3%, 1.2%, and 0.8%, respectively). The countries with the highest ratios are Montenegro (10.2% for its electricity exports) and Iceland (7.5%, exclusively for aluminum), which appear to be the main « winners » in Europe on this criterion.

In the rest of the world, the share of exports in GDP tends to be more moderate, especially in the BRICS countries, due to the negligible amount compared to the size of their GDP. Only four countries have a ratio above 1%: Turkey, Trinidad and Tobago, Bahrain, and Mauritania, with the latter standing out with a ratio of 3.1% thanks to its steel exports.

2nd criterion – Export market share

The export market shares by product of non-EU countries rarely exceed 6%, with a few exceptions (19.4% for Norway in hydrogen and 12% for Russia in fertilizers). Therefore, this analysis is limited to market shares without taking into account those of EU countries, which provides a better picture of competition between non-EU economies. The map below illustrates these comparisons, showing only countries with a significant market share (above 5%). The darker blue a country appears, the more significant its market share is among the six product categories subject to the MACF (see footnote 3).

The big « winners » appear to be Russia and the United Kingdom, with four product categories in which they have a significant market share. Russia performs strongly in fertilizers and aluminum (26.8% and 10.1% of export market share, respectively), and the United Kingdom in cement (12.8%). China, Norway, Turkey, and Brazil have significant shares for three products. By product category, China appears to be the main « winner » for steel (17.7%) and aluminum (12.2%), a product for which Norway ranks first (14.2%). For cement, Turkey and the United States have the largest market shares (19.8% and 15% respectively), North African countries fare well in fertilizer exports (especially Algeria and Egypt), while energy products are dominated by European countries (Switzerland for electricity and Norway for hydrogen).

Third criterion – Carbon intensity of exports

The objectives of reducing greenhouse gases and carbon emissions are not unique to Europe and are part of a global approach.Some countries have already established a carbon market, andit seems logical that other countries should follow suit. It seems logical that the carbon intensity of products should play an increasingly significant role in competitiveness criteria, apart from the cost of the products traded. Based on this general observation and in view of the challenges posed by the MACF, countries that export the least carbon-intensive products have a role to play in meeting European demand.

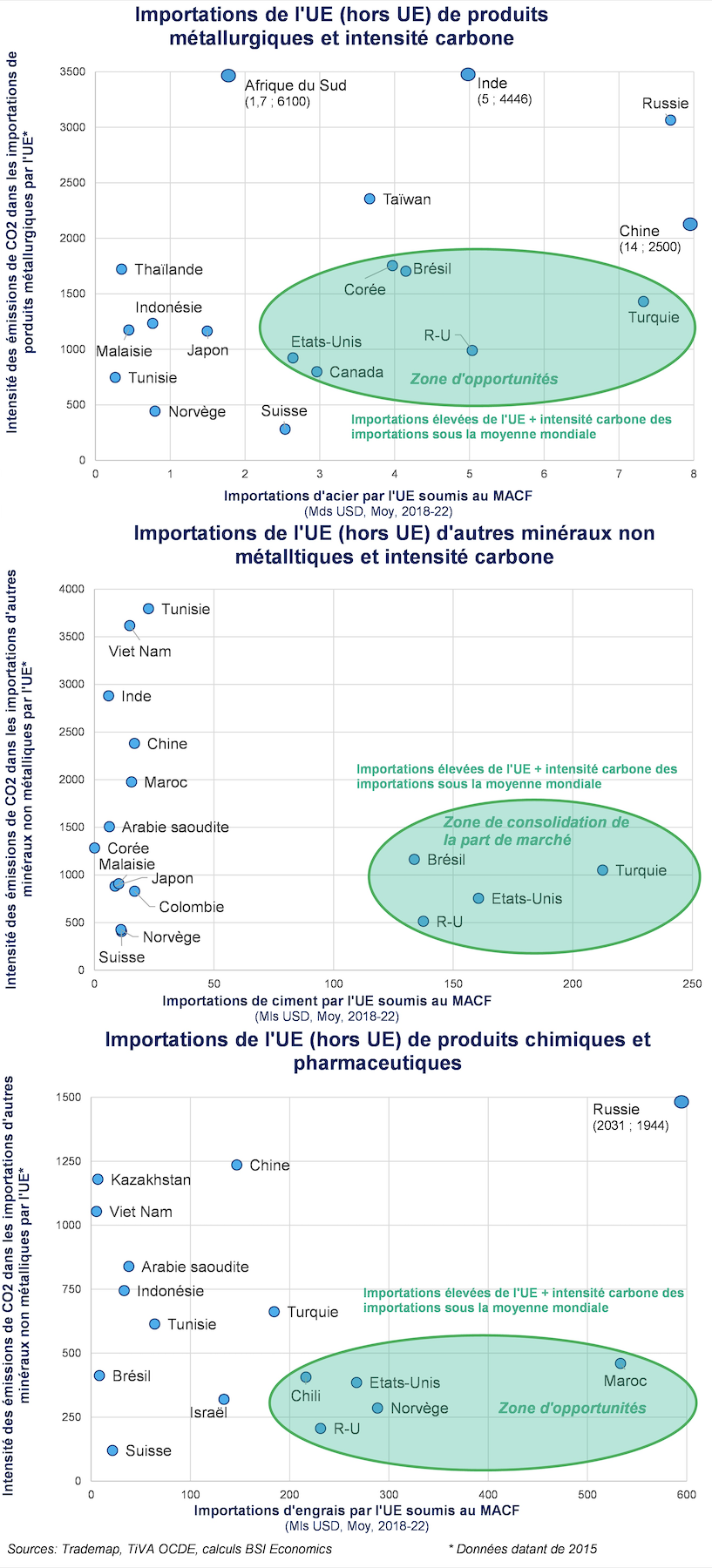

The OECD’s TiVA database can be used to rank countries according to carbon intensity by major category of products imported by the EU. By cross-referencing this information with the volume of EU imports for these product categories by country, it is possible to identify the countries with the greatest potential. The three graphs below provide a visual overview of the respective positioning of countries for metallurgical products (steel and aluminum), other non-metallic mineral products (cement), and chemical and pharmaceutical products (nitrogen fertilizers), with the green areas grouping together countries with high potential:

- Metallurgical products: despite significant export volumes to the EU, Russia and China could well lose market share due to the very high carbon intensity of their exports to the EU at this stage. However, this does not take into account the case where these countries no longer export directly to Europe but indirectly via countries with a lower carbon intensity. In this scenario, clarity and transparency in reporting procedures are key to promoting effective competition based on the carbon intensity of products. Turkey appears to be a potential « winner, » combining high exports with relatively low carbon intensity. Export volumes for the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom are certainly lower, but they benefit from even lower carbon intensity than Turkey. To a lesser extent, South Korea and Brazil also show potential.

- Other non-metallic mineral products: four countries have relatively significant market shares compared to their competitors. These same four countries also have some of the lowest carbon intensity of their exports to the EU: Turkey, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Brazil. In view of these results, and the low export volumes of countries with lower carbon intensity (Switzerland and Norway, for example), they should consolidate their market shares in the event of an increase in EU demand.

- Chemicals and pharmaceuticals: Russia’s dominant position in the European market could eventually be challenged by the very high carbon intensity of its exports. While four countries show potential (Norway, the United States, Chile, and the United Kingdom) with low carbon intensity in their exports, a fifth country stands out: Morocco. However, given the country’s results forthe secondcriterion (export market share of only 3.2% for nitrogen fertilizers), this good performance should be put into perspective, as it includes a wider range of chemical products than just nitrogen fertilizers.

While the creation of the MACF is to be welcomed in view of its ambition to preserve the competitiveness of European industries and support them on the path to decarbonization, its current configuration may raise many questions and criticisms.

Nevertheless, it seems a little early to draw conclusions about the impact of the mechanism, which is likely to be revised by 2025 (probably extended to glass and ceramics), which will probably result in other « winners » and/or « losers, » both within and outside the European Union. Furthermore, certain effects will depend in particular on other equally important aspects, such as the phasing out of free allowances, aid plans to support the decarbonization of industries, and the trajectory of carbon prices.

[1]For more information on this subject, see the sections on the evolution of theETS Directive.

[2]This phenomenon of leakage consists of relocating the industries that emit the most greenhouse gases outside the EU so that these industries do not have to bear the costs associated with the new environmental standards.

[3] As a reminder: steel, aluminum, nitrogen fertilizers, cement, electricity, hydrogen, see previous article.