DISCLAIMER: The opinions expressed by the author are her own and do not necessarily reflect those of the institution that employs her.

Summary:

- The agreement reached at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, did not allow for greater ambition on the part of the international community to phase out fossil fuels, contrary to the conclusions of the IPCC and the International Energy Agency to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 and limit global temperature rise.

- The sustainability challenges of developing and low-income countries’ debt in the face of the growing physical effects of global warming were prominent in the discussions and negotiations. Reflections on the international financial architecture will be a key topic for 2023.

- The integrity of the financial sector’s commitments, the development of transition plans aligned with scientific recommendations, and financing mechanisms for the transition away from fossil fuels are key regulatory and supervisory issues for 2023, in the wake of the discussions and agreements that emerged from COP27.

Three months have now passed since COP27 on climate change. Its mixed results have been widely commented on: little noticeable revision of nationally determined contributions, limited action on phasing out fossil fuels, and timid progress in the international community’s response to climate change. In this context, what conclusions can be drawn for the financing of climate action and the management of climate risks in the financial system?

Without claiming to provide an exhaustive assessment, given the diversity and complexity of the challenge of financing the energy and ecological transition, this article reviews the key advances and limitations ofthe Sharm el-Sheikh Agreementand the priorities of the international agenda for 2023.

1. A lack of ambition in phasing out fossil fuels, reflecting the dependence and inertia of economies in terms of energy

The agreement reached at COP27 was described as a » mixed bag » by Nature magazine. While it reiterates the need to accelerate efforts to limit the global average temperature increase to around 1.5°C, it does not address the essential issue of phasing out fossil fuels. However, the 1.5°C target now remains virtually impossible to achieve, according to the IPCC, which states in its sixth assessment report (2021-2022): » global warming of 1.5°C and 2°C will be exceeded during the 21st century unless deep reductions in CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions occur in the coming decades. »

Admittedly, paragraphs 13 and 14 of the agreement emphasize the acceleration of policies for the deployment of low-carbon technologies, energy efficiency measures, and measures related to the (drastic) reduction of methane emissions—without, however, raising the level of ambition ofthe Glasgow agreement resulting from COP26. The only points highlighted are 1. the phasedown of coal-fired power generation without the use of carbon capture and storage technologies; and 2. the phasing out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, which are expected to increase to 7.4% of global GDP by 2025 (IMF, 2022).

Furthermore, the agreement reflects neither the conclusions of the IPCC nor those of the International Energy Agency in its net-zero scenario (2021) and its 2022 report on coal, both of which highlight the urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions fromall fossil fuels and the harmful effects of policies and infrastructure that lead to carbon lock-in. The growth in investment in new fossil fuel infrastructure around the world in 2022, particularly coal-fired power plants due to rising gas prices following the invasion of Ukraine, is evidence of the persistent risks of lock-in. The energy context and the role played by the oil and gas industry in the discussions probably had an impact on the nature of the agreement. However, the cumulative future greenhouse gas emissions projected over the lifetime of existing and currently planned fossil fuel infrastructure exceed the total cumulative net emissions in pathways that limit warming to 1.5°C, without overshoot or with limited overshoot. In addition, demand for coal alone increased by around 1.2% in 2022, reaching a historic high with production exceeding 8 billion tons for the first time. However, in order to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, global coal consumption would need to decrease by around 45% by 2030 and 90% by 2050. The International Energy Agency has published a report on coal in the transition to carbon neutrality (IEA, 2022), highlighting both the immense challenge of such a transition and the existing obstacles (rules on competition and access to electricity markets; high weighted average cost of capital; lack of flexibility in electricity systems, etc.). Solutions in terms of regulation, innovative financing, the development of low-carbon alternatives, and a just transition (training and workforce management) are possible but complex to achieve, particularly in developing countries.

Given the different impacts of warming at +1.5°C and +2°C (WRI, 2022), the agreement does not reflect measures commensurate with the aggravated impacts of warming on drought levels, precipitation cycles, ice melt, sea level rise, biodiversity erosion, food security, public health, and economic growth. Furthermore, warming of 1.5°C or 2°C carries a different level of uncertainty about the crossing of tipping points ( IPCC, 2018), beyond which a system reorganizes itself, often abruptly and/or irreversibly.Examples of such tipping points include the disappearance of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, the mass mortality of tropical coral reefs, the abrupt thawing of permafrost, and the shutdown of the North Atlantic Ocean current (McKay et al. 2022).

2. Mobilization of financial resources

The financial sector and the integrity of its commitments

First, the financial system has a key role to play (Title IX of the Sharm el-Sheikh Agreement), given the persistent misallocation of capital (Robins, 2022) and the growing targets for financing mitigation and adaptation (estimated at $4 to $6 trillion per year for a global transformation of our economies). Paragraph 31 is a call to order given the existing—limited—measures for sustainable finance, calling for » a transformation of the financial system and its structures and processes, engaging governments, central banks, commercial banks, institutional investors, and other financial actors »—which further questions the effectiveness and ambition of current financial sector policies.

Following the launch of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net-Zeroat COP26 – which has both enabled some progress in the financial sector’s commitment to the transition (500 members, publication of guidelines on« net-zero » transition plans by financial institutions) and demonstrated the limits of voluntary commitments (Financial Times, 2022) – the challenge of reallocating private capital has only been reinforced. Above all, the integrity of financial institutions’ net-zero strategies has become a major topic of regulation and supervision, with the publication of the Integrity Matters report under the auspices of the United Nations Secretary-General; the publication of gradually mandatory guidelines and standards on transition plans (United Kingdom, European Union, United States, etc.); and the launch of a discussion among supervisors on the role of financial institutions’ prudential transition plans and their supervision (NGFS, Financial Stability Board, Basel Committee, etc.).

The climate and sovereign debt nexus

The agreement highlights this dilemma, particularly in paragraph 32: » Notes with concern the growing gap between the needs of developing country Parties, in particular those due to the increasing impacts of climate change and their increased indebtedness, and the support provided and mobilized for their efforts to implement their nationally determined contributions, highlighting that such needs are currently estimated at USD 5.8–5.9 trillion for the pre-2030 period. »

This is the first time that the issue of debt has been given such prominence in a COP agreement.The energy crisis, particularly as a result of the war in Ukraine, inflation, and the normalization of monetary policy in the United States and Europe have had particularly significant consequences for developing countries, especially those that import energy (depletion of foreign exchange reserves; reduced economic growth; increased inequality; increased liquidity risk; increased use of debt as a mechanism for insuring against natural disasters). In this context, new instruments are being developed, notably catastrophe bonds (IMF, 2022) and instruments linked to the achievement of specific climate, environmental, or ESG performance indicators (known as » sustainability-linked » instruments), such as sustainability-linked bonds (IMF, 2022, World Bank, 2022, Jain, 2022).

According to the IMF (2022), more than a quarter of developing economies are in default or distress in terms of government bonds, and 60% of low-income countries are at high risk of over-indebtedness. A possible « vicious circle » (Espinoza, Volz, and Li, 2022) is possible, between the intensification of the physical effects of climate change, low investment in mitigation, adaptation, and resilience, increased sovereign risk and cost of capital, and… debt sustainability (High Level Expert Group on Climate Finance, November 2022).

This is what led Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley to proposethe Bridgetown Agenda, an action plan aimed at ensuring that the international community provides the necessary financing to the countries most vulnerable to global warming, beyond » debt-for-climate swaps » – via emergency cash injections by the International Monetary Fund, improved lending by multilateral development banks, and new financing mechanisms (Persaud, 2022).

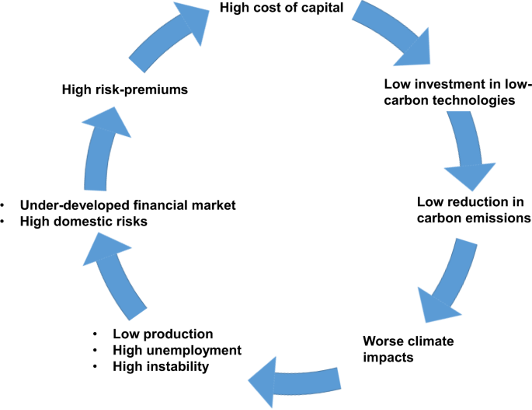

However, access to low-cost financing for the deployment of renewable energies is uneven, as the cost of capital varies considerably from one region to another (Ameli et al. 2021). Developing countries suffer from a « climate investment trap » (see chart below), which occurs when climate-related investments remain chronically insufficient due to a set of self-reinforcing mechanisms, the dynamics of which are similar to those of the poverty trap. Investors’ perceptions of high risk lead to high premiums, increasing the cost of capital for low-carbon investments and thus delaying the energy system transition and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. However, uncontrolled climate change would have a greater impact in these countries, affecting production systems and reducing economic output, generating unemployment and political instability, which would further increase the perception of risk. This was highlighted in a recent IMF note (2022) on high upfront costs, the long-term horizon of infrastructure projects, and the risks associated with investments in mitigation and adaptation (currency risk, regulatory and political risks, macroeconomic and trade risks, and technical risks) that play a major role in deterring such investments in emerging and developing economies.

The « climate investment trap »

Source: Ameli et al. 2021 (here)

In this context, for the first time in a COP agreement, two paragraphs directly address the role of international financial institutions and multilateral development banks. The agreement calls for reform of these institutions’ practices in order to increase their climate financing and use all the tools at their disposal, particularly with a view to greater mobilization of « private » capital. In this sense, it directly echoes the conclusions of the IMF (2022) in its report on global financial stability, which highlights both the role of the IMF (particularly through the new lending facility – the Resilience and Sustainability Facility) and the need to rely on new climate finance instruments and invest more inequity.

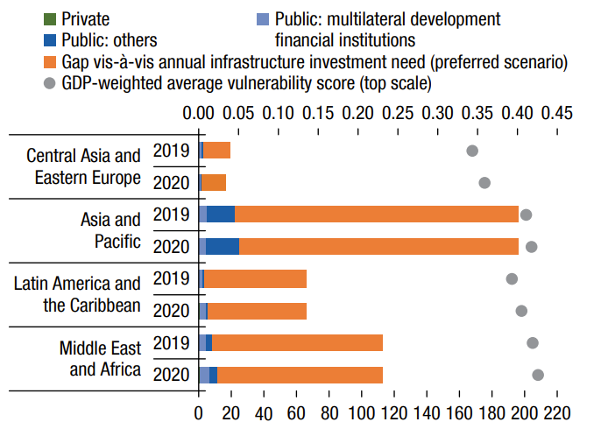

Financing adaptation and loss and damage

The member countries of the Climate Vulnerability Forum (55 developing countries) have calculated that they have lost 20% of their national income over the last two decades due to the impacts of global warming. The COP27 agreement therefore devotes two sections to the increased need for adaptation financing, given the considerable financing gap (shown in orange in the graph below). It outlines (still in very general terms) a fund dedicated to financing loss and damage forlow- and middle-income countries in order to offset the costs of global warming. These discussions followed on from those relating to the failure to meet the target of mobilizing $100 billion per year for developing countries by 2020 (set at COP16 and reiterated at COP21) (Timperley, 2021, OECD, 2022).

Global financial flows for adaptation, investment needs in adaptation infrastructure, vulnerability score by region (millions of US dollars, vulnerability score)

Source: IMF, 2022 (Chapter 2 of the Global Financial Stability Report)

Adaptation financing suffers from market failures and key coordination problems (Bellon and Massetti, 2022), particularly in emerging and developing countries: uncertainty surrounding climate risks; lack of understanding of the learning cycle to address issues of uncertainty surrounding adaptation; insufficient risk pricing; insufficient access to existing climate data and models; lack of bankable projects; under-application of investment taxonomies around climate resilience; anticipation of socialization of reconstruction by the public sector; methodological flaws in ESG scores (including, in particular, an income bias—see Moussavi and Karapandza, 2022, IMF, 2022). Although sources of private financing for adaptation are emerging (green and social impact bonds, resilience bonds, dedicated investment vehicles, etc.), they remain limited. It therefore remains essential for international financial institutions and multilateral development banks to increase their role in identifying specific adaptation projects suitable for large-scale private sector investment, in addition to their own financing of adaptation projects in developing countries (IMF, 2022).

In particular, the role of data andearly warning mechanisms is included in the Sharm el-Sheikh agreement, given their key economic value in developing countries facing the effects of climate change (here), and in the wake of an international action planto increase investment in meteorological infrastructure by $3 billion by 2027.

And 2023?

There are many challenges for 2023, given the climate emergency and the urgent need to realign capital flows on a path compatible with carbon neutrality targets. The effects of the policies pursued in 2022 on the effective transition of energy systems (risks of greenhouse gas emissions lock-in) and on the macroeconomic sustainability of developing countries will need to be assessed. With a view to COP28, which will take place in the United Arab Emirates, the international agenda is broadly organized around the following priorities:

– The systemic transformation of the financial system. For example, beyond transparency measures, will regulation move towards the publication, monitoring, and implementation of transition plans and targets?

– The key role of finance ministries (here) and central banks (here) in designing and implementing climate-related macroeconomic policies and in managing and supervising climate risks.

– The challenge of reorganizing the international financial architecture in the face of the debt-climate nexus; and

– The goal of a just energy transition (here) and the management of the transition of existing and new coal and oil and gas infrastructure.

***

For a reminder of the objectives and functioning of the « conferences of the parties »: What to expect from COP27 this year, the United Nations Climate Change Conference (unep.org)