Summary:

– The ECB’s negative interest rate policy, recently imitated by the Swiss National Bank, continues to be widely interpreted as a measure aimed at « penalizing banks that do not lend to households or businesses » and therefore as a measure to encourage lending.

– We explain that this is not the case at all.

– To do so, we discuss the arguments put forward in one of the major articles, often cited, which conveys this idea of an « incentive measure. »

– We explain: 1) that since 2012, the amounts placed in the ECB’s deposit facility are irrelevant for drawing any conclusions about the behavior of banks 2) that the negative interest rate measure is in no way a response to the large amounts placed in the ECB’s deposit facility 3) that a bank does not dispose of its liquidity through a credit transaction; 4) that banks do not dispose of their liquidity through their purchases of securities; 5) that no « incentive effect » on credit can be expected from this measure (for the positive effects, see our BSI focus).

The now famous « negative interest rate » measure (see our insight here) was taken last June by the ECB and recently imitated by the Swiss Central Bank. Since then, as we pointed out very early on in Le Monde, as did others (Peter Stella, former director at the IMF, here), this measure has been commented on with a great deal of confusion. The main message conveyed has been as follows: negative interest rates would act as a « stick » to punish banks that do not lend to households and businesses, and would therefore ultimately be a means of encouraging lending. This message does not make sense, but continues to be propagated nonetheless. Our BSi Economics focus last September (page 7 here) already attempted to clear up this confusion in general terms, while offering an interpretation of this measure. Here, we are changing our approach by commenting directly on an article from a source considered « reputable » but which relays the message and preconceived ideas that have shaped the misinterpretation of this measure [1]. We will quote directly from certain passages of this article and discuss them in turn.

– « Since 2008, the amount of deposits left with the ECB has fluctuated to a greater or lesser extent depending on the uncertainties linked to the sovereign bond crisis. The peak of the crisis in spring 2012 coincided with the maximum amounts deposited by banks with excess liquidity. »

Let’s start with a brief remark: the sharp increase in the amounts placed in the deposit facility in early 2012 was simply the result of the LTROs conducted by the ECB on December 21, 2011, and March 1, 2012. These loans, worth €489 billion and €529 billion respectively [2], automatically resulted in an increase in liquidity. Banks as a whole then had two choices: (i) to place the liquidity obtained in the deposit facility at 0.25% interest or (ii) to leave it in their non-interest-bearing current accounts. Logically, they chose the first option: the amounts placed in the deposit facility exploded with the LTROs.

The significant increase in the amounts placed in the deposit facility in 2012 is therefore primarily a natural consequence of the ECB’s policy (LTRO in this case).

« Amid fears of a breakup of the eurozone and uncertainty about the financial situation of financial and non-financial agents, banks deposited very low-interest amounts with the ECB. They made this choice rather than trading this excess liquidity on the money market or supporting activity by granting loans to businesses or acquiring financial securities. »

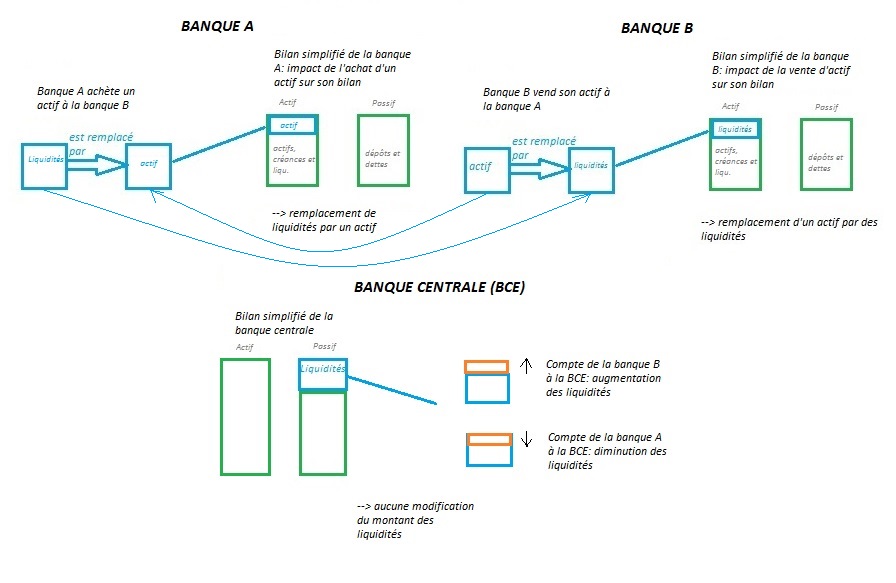

The second part of this argument suggests that banks as a whole would have the choice between placing their excess liquidity with the ECB or investing it in securities or loans. In other words, with the granting of loans or the purchase of securities, the excess liquidity would disappear. Let’s first look at what happens in accounting terms when a bank purchases a security. Suppose that Bank A has a large amount of excess reserves placed in the deposit facility and wishes to purchase a security to dispose of them, either from another bank (case number 1) or from a company (case number 2).

Case number 1: purchase of securities from another bank

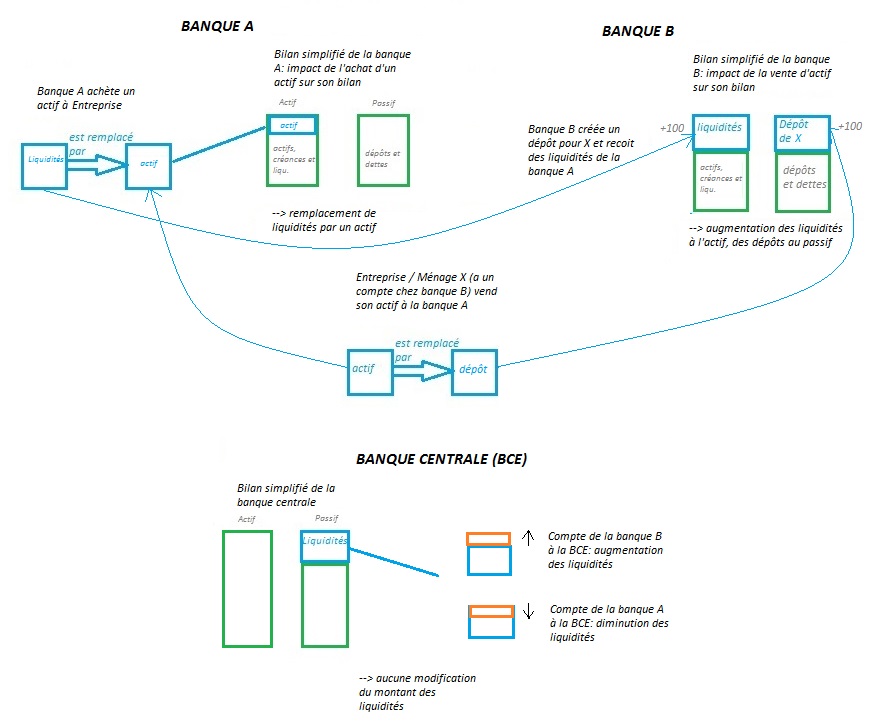

Case number 2: purchase of a security from a company or individual:

Bank A will have transferred its cash to Bank B. If Bank B already has enough cash in its current account to meet its reserve requirements (there is no reason for this to change [3]), it will place the amount in the deposit facility. If it did not have enough, this means that without this cash injection, it would have borrowed reserves from a bank that had excess cash in the deposit facility. The transaction therefore ultimately changed nothing.

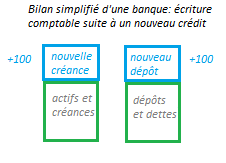

The same conclusion applies to a credit transaction. A credit transaction does not directly change the amount of liquidity a bank has [3]. A credit transaction is simply an accounting entry, whereby a bank credits the deposit of an individual or a company with a certain amount while increasing its « receivables » item on the liabilities side.

Securities purchases or loans do not therefore automatically result in a decrease in excess liquidity. Banks as a whole cannot get rid of their reserves by buying securities; they can simply transfer them to other banks [4].

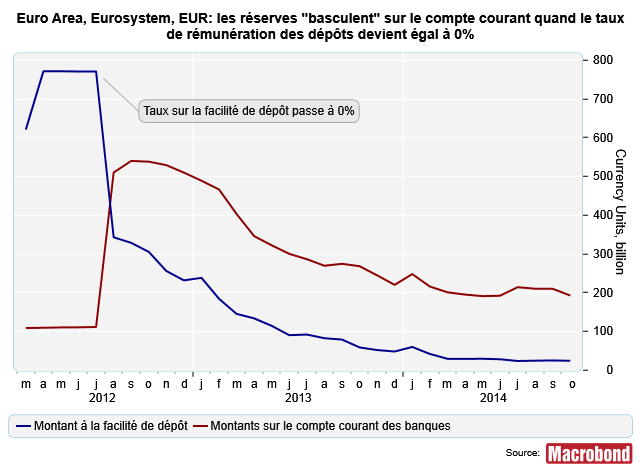

It was not until Mario Draghi’s July 2012 statements announcing that he would do whatever it takes to support the eurozone that confidence returned and these amounts began to decline. This was also when the rate was lowered to 0%, further reducing the incentive to use deposit facilities. Deposits immediately fell by half, from €795.2 billion to €386.8 billion. »

Indeed, the amounts placed in the deposit facility fell dramatically after the « Whatever it takes » announcement… but where did they go? The answer is simple: to the banks’ current accounts. As these accounts do not earn interest, banks normally prefer to use the (interest-bearing) deposit facility for their excess reserves. Once the deposit rate becomes 0%, banks have no reason to place their cash in the deposit facility rather than in their current accounts: the amounts in the deposit facility become arbitrary. Banks therefore simply left their cash in their current accounts at the end of each day, which explains why the deposit facility halved. The amounts ended up in the current account, as can be seen in the chart below.

When the rate on the current account is the same as the rate on the deposit facility, the amounts placed in the deposit facility become arbitrary and do not reflect any strategic decisions by the banks.

– « Thus, in the last week of May 2014, deposits still amounted to €40 billion. This observation prompted the ECB to propose negative rates in order to encourage commercial banks to reallocate these amounts. »

Beyond any possible reallocation effects (not to businesses, but only between banks themselves), it seems highly unlikely that the high amount of funds placed in the deposit facility was the factor that prompted the ECB to propose a negative rate. This is firstly for the reasons we outlined above, but also because the amounts placed in the deposit facility will de facto increase with the measures recently implemented by the ECB (purchases of covered bonds and ABS) and those to follow. The increase in the Eurosystem’s balance sheet to €3 trillion will inevitably lead to an increase in excess liquidity, and in this context it seems clearly illogical for the ECB to have put in place a measure to combat a « problem » that it will itself recreate.

– « Let’s bet that as soon as this negative rate is applied, deposits will quickly become zero. »

These deposits may become zero insofar as banks will be indifferent between placing their excess liquidity in their current account or in the deposit facility (the negative rate applies in both cases), and only the former is used for the bank’s daily operations. But whether the reserves are in the current account or the deposit facility, it doesn’t make much difference in our framework (all excess reserves are taxed). We can bet that after the LTRO repayments in early 2015, with the purchases of ABS and covered bonds and future complementary measures, excess liquidity will increase, simply because banks as a whole, with the exception of the LTRO repayments in December 2011 and March 2012, cannot significantly reduce their reserves. They can transfer them between themselves, but they cannot reduce them at will [4]. From this perspective, a negative rate is not intended to punish banks that do not lend, nor to reduce the amounts placed in the deposit facility. The aim is elsewhere, as we have already discussed previously (see p. 7 of our BSi focus here).

J.P.

Notes:

[1] Since the purpose of our contribution is not to discredit the authors of this article but rather to address the confusion it conveys, we do not refer directly to the article in question.

[2] More information here https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/omo/html/index.en.html. It should be noted that with these 3-year LTROs, other shorter-term LTROs were abandoned by the banks.

[3] There is no increase in reserve requirements since the calculation of reserve requirements is based on the deposits held by the bank two months earlier in the eurozone (otherwise, 1% of the amount of the transaction would have to be placed in reserve requirements, i.e., 1% of the amount of cash would have to migrate from the deposit facility to the current account, mechanically speaking -only-). It should be noted in passing that the argument that the incentive effect of the negative rate comes from reserve requirements does not make sense either: assuming that an incentive effect exists, it will be the same whether the interest rate on deposits is negative or positive, since the difference in remuneration between the rate of return on reserve requirements and the rate of return on deposits (opportunity cost) remains the same.

[4] For the sake of completeness: banks can get rid of their excess reserves by exchanging them for banknotes (which they do not do because it is costly), by repaying their loans to the central bank (which they have done with LTROs recently) or by conducting transactions with the Treasury. These cases are not relevant to the analysis we are proposing here.

Other useful resources on this topic:

« The base money confusion » FT Alphaville http://ftalphaville.ft.com/2012/07/03/1067591/the-base-money-confusion/

« The Negative Rate Chrono Synclastic Infundibula » Peter Stella (former Director of the Central Banking Department at the IMF) http://stellarconsultllc.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/The-Negative-Rate-Chrono-Synclastic-Infundibula.pdf