Abstract:

– Economists generally predict that political parties will converge on similar positions during municipal elections.

– Empirical verification of this prediction is difficult but possible. Overall, it would appear to be true, with some possible exceptions.

– In France, a very preliminary analysis shows convergence on the issues of housing and local taxes. However, this analysis is too preliminary to constitute definitive proof.

With municipal elections approaching in France, BSI Economics presents economic research devoted to these elections, particularly that dedicated to the issue of partisan bias among political parties. Among economists, there is near consensus that ideological differences between political parties are of minor importance during elections, particularly local elections. According to them, the influence of the « Median Voter » will generally be too strong for political parties to stray too far from it. After justifying this consensus, this article will present some of the empirical results on the convergence of political parties to similar positions during municipal elections. Finally, we briefly present preliminary results on French cities.

1 – A little theory: the convergence of political parties

Most economic models involving political decision-making use the « Median Voter Theorem. » This theorem states that if voters can be classified on a segment according to their preferences on the issue at hand, then the decision preferred by the median voter (on the segment) will be chosen.

For example, if agents’ preferences regarding taxation depend on their income, then the level of taxation to be determined will be the preferred level of the person earning the median income. Intuitively, for any counterproposal (a higher or lower level of taxation), at least half of the population will prefer the median voter’s proposal.

The introduction of two political parties does not change this result, and in this case, the theory predicts that these two political parties will converge towards a common proposal: that of the median voter. Indeed, if one of the parties deviated and proposed a different policy, more than half of the electorate would choose its rival, and it would be certain to lose the election.

Of course, several factors can prevent political parties from converging towards a common position. These include the preferences of political parties associated with uncertainty about the position of the median voter, the presence of more than two political parties (for example, a third party seeking to maximize the number of votes obtained), or the presence of activists defending opposing positions in each camp (otherwise these activists should rather be analyzed as pressure groups pushing political parties to adopt the same policy, but not necessarily that of the median voter) are all factors that lead political parties to choose different policies.

These few factors explain why, at the municipal level, economists generally believe that parties converge toward similar positions. In particular, they emphasize the relative homogeneity of the electorate (within cities), which leads to low uncertainty about the desires of the « median voter. » In the absence of uncertainty, it would be too risky to stray from the median position.

This homogeneity would naturally be reinforced by the phenomenon of « voting with one’s feet, » described by Tiebout in 1956. A voter who disagrees with the policies pursued in a city could simply decide to move away (or not to move there in the first place). Ultimately, this mechanism would lead to a homogenization of the electorate (this mechanism would also lead to relatively effective local policies). This mechanism, which is less credible in France than in the US (where population mobility is high), could nevertheless lead in the long term to cities where voters are not very diverse (particularly in small suburban towns), and therefore to political parties that most often choose the same policies within these cities.

Furthermore, policies implemented at the municipal level can sometimes be more « technical » than « ideological. » In this case, the challenge of the election would be to differentiate oneself in terms of quality (the most competent candidate), i.e., vertical differentiation rather than horizontal differentiation (as in the median voter model, where policies are different but not ranked by quality).In this case again, political parties would propose similar policies and the question would then be which candidate would be best suited to implement them.

In practice, certain factors can complicate these convergences. The presence of more than two parties has already been mentioned, and a few examples can illustrate this problem. Suppose, for example, that a right-wing party fears that a far-right candidate could make it to the second round. To avoid this problem, the right-wing Republican party could choose a « more extremist » position in order to prevent the far-right party from obtaining 10% of the vote (and thus being able to remain in the second round). Similarly, a left-wing party could adopt « more extremist » positions in order to secure a merger between the two rounds with a far-left or environmentalist candidate. These two examples can of course be reversed; they are motivated by the fact that, while mergers between left-wing and far-left parties are common, they are rarer on the right.

Theoretical economics therefore tends to conclude in favor of political party convergence, albeit with some reservations and exceptions. Let us now analyze the empirical articles.

2 – The empirical challenge: determining the position of political parties

Determining the positions of political parties is a real statistical challenge. There are two difficulties to overcome: the first is to separate the preferences of the electorate from those of the political parties, and the second is that we do not simultaneously observe a municipality with a « left-wing » mayor and a municipality with a « right-wing » mayor: it is not possible to analyze the policies implemented by the party that loses the election and/or is in the minority on the city council. Thus, it is not possible to directly compare the differences between cities where the left is elected and those where the right is elected in order to determine the differences or similarities between political parties.

For example, we may observe lower local taxes in cities that have elected a right-wing mayor, but this is not informative. Left-wing competitors may have proposed the same tax levels and lost the election on another issue, due to a more mobilized right-wing electorate, etc. In this case, we would conclude that there is a difference when in fact there is none.

The ideal way to measure the impact of a political party would be to randomly determine whether a city will be run by the left or the right, and then compare cities that are « identical in every respect » except for the political party. Moreover, if the decision is truly random, the cities will have identical averages in both groups, and it would suffice to compare the differences in the policies implemented.

A method called « regression discontinuity design » allows us to approximate this random method. Intuitively, when elections are very close between a left-wing candidate and a right-wing candidate, we can consider that, very locally, the winning party is determined randomly. By comparing the policies implemented in cities where a left-wing candidate and a right-wing candidate were neck and neck, it is then possible to measure the average (local) effect of electing a left-wing party relative to a right-wing party. This method has become popular among political analysts and has been used in various contexts. In particular, Ferreira and Gyourko (2009) show that in the United States, cities run by Democrats and Republicans do not differ in terms of public spending, the allocation of public spending, or (the fight against) crime. This result supports the theoretical finding in the previous section: the local level is not the right place to observe ideological differences between candidates.

However, there are counterexamples. Pettersson-Lindbom (2012), for example, show that left-wing Swedish municipalities levy higher taxes and have lower unemployment rates, often due to more public sector jobs. Similarly, Albert Solé-Ollé and Elisabet Viladecans-Marsal (2012) show that in Spain, cities run by left-wing parties declare less new land available for construction. These results also confirm economic theory with its emphasis on the homogeneity of cities and competition between neighboring municipalities (echoing the Tiebout mechanism).

3 – Application to France: the case of building permits and the housing tax rate

It therefore seems difficult to determine a general answer to the question: is the political affiliation of candidates a relevant variable at the local level? We are not aware of any analysis of partisan bias in French municipal elections. However, it is possible to compare certain French cities in terms of local taxes and housing construction.

The results presented here are very preliminary. They are part of a research project conducted by the author of this article, which is still in its initial stages. The methodology used is that of « regression discontinuity design » to estimate the differences between « left-wing » and « non-left-wing » (center, unaffiliated, and right-wing) cities. Restricting the sample to left-wing and right-wing cities does not affect the preliminary results, which is why we often use the terms « left » and « right » (instead of « non-left ») in a somewhat loose sense. Furthermore, « left » and « right » are to be taken in a generic sense; no distinction is made between, for example, the PS, the Greens, or the Communists.

We do not present the methodology used in greater detail (but interested readers can contact the author of the article for more details), but we emphasize once again the preliminary nature of these analyses. These results, although supported by analyses that we hope are serious, do not yet constitute « scientific proof. »

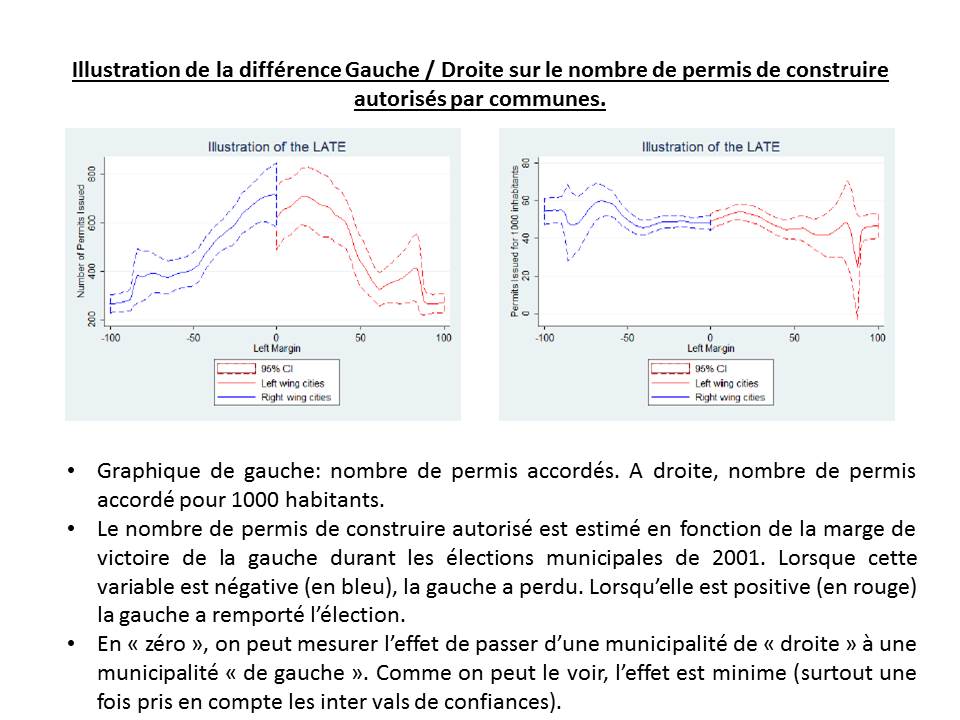

The graph above shows the low impact of a change in the political color of a city council. The causal impact can only be read as « zero »; elsewhere, it may be biased by many factors. For example, we observe that cities where mayors score very highly issue few building permits. It is not because of low urban growth that these mayors obtain high scores (or vice versa), but simply because mayors elected with scores close to or equal to 100% are elected in small towns. These small towns authorize the construction of fewer new homes.

The causal effect of the election of a « left-wing » mayor on housing (measured at zero) is modest or insignificant. Please note that this result only concerns the number of housing units authorized. Their size or type (e.g., social housing or not) is not taken into account here. Furthermore, issues related to inter-municipal cooperation are not included in the analysis (however, these results concern the period 2002-2007, when inter-municipal cooperation still played a more modest role in housing).

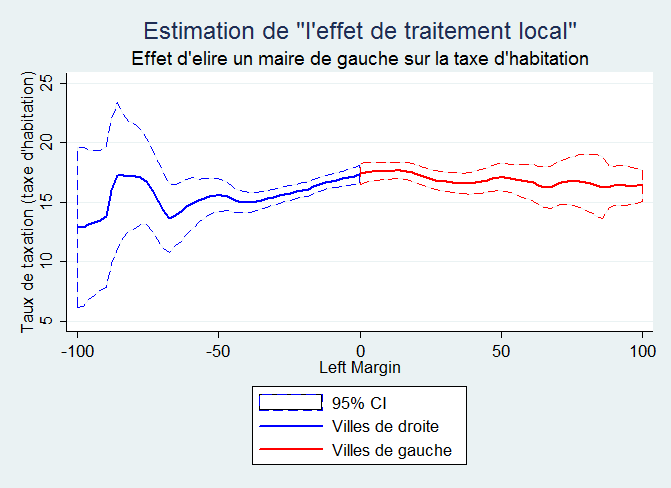

The graph below presents a similar analysis, but for the rate of the housing tax. Once again, the effect of electing a left-wing mayor is weak. This result remains similar whether we consider the total housing tax base in the city (since cities may include exceptions) or analyze other local taxes such as property taxes on built and unbuilt land.

Of course, it is possible to perform « non-graphical » analyses to ensure the validity of these results. In this case too, it would appear that the differences in management between « left-wing » and « right-wing » parties are small in terms of housing and taxation.

Conclusion:

Economists generally agree that political parties will propose similar policies during municipal elections. This convergence can be explained by electoral competition: if one party differs too much from the others, it is highly likely to lose the election. However, there are exceptions to this rule.

Empirically, it is difficult to decide: in the United States, it would seem that political parties implement the same policies at the local level, but in other countries, there are more significant differences.

In France, a (very preliminary) analysis shows convergence on the issues of housing and local taxes. There are, of course, other dimensions, and it is impossible to conclude that there is overall convergence. Nevertheless, on these issues, it would seem that electing a left-wing or right-wing city council has relatively little impact.

References:

– Fernando Ferreiraand Joseph Gyourko, Do Political Parties Matter? Evidence from U.S. Cities, The Quarterly Journal of Economics(2009) 124 (1): 399-422.

– Per Pettersson-Lindbom, Do Parties Matter for Economic Outcomes? A Regression Discontinuity Approach, Working paper, 2012.

– Albert Solé-Ollé, Elisabet Viladecans-Marsal, Do political parties matter for local land use policies, IEB Working Paper, 2012.