Summary

– Economic inequality in France has been increasing since the mid-2000s and is now at the OECD average.

– The classical theory predicting a positive relationship between the level of economic inequality and economic growth has been undermined by recent empirical studies.

– It would appear that economic inequality leads to a risk of economic crisis, a deterioration in a country’s environment and education levels, and an increase in crime and political instability.

Inequality in France

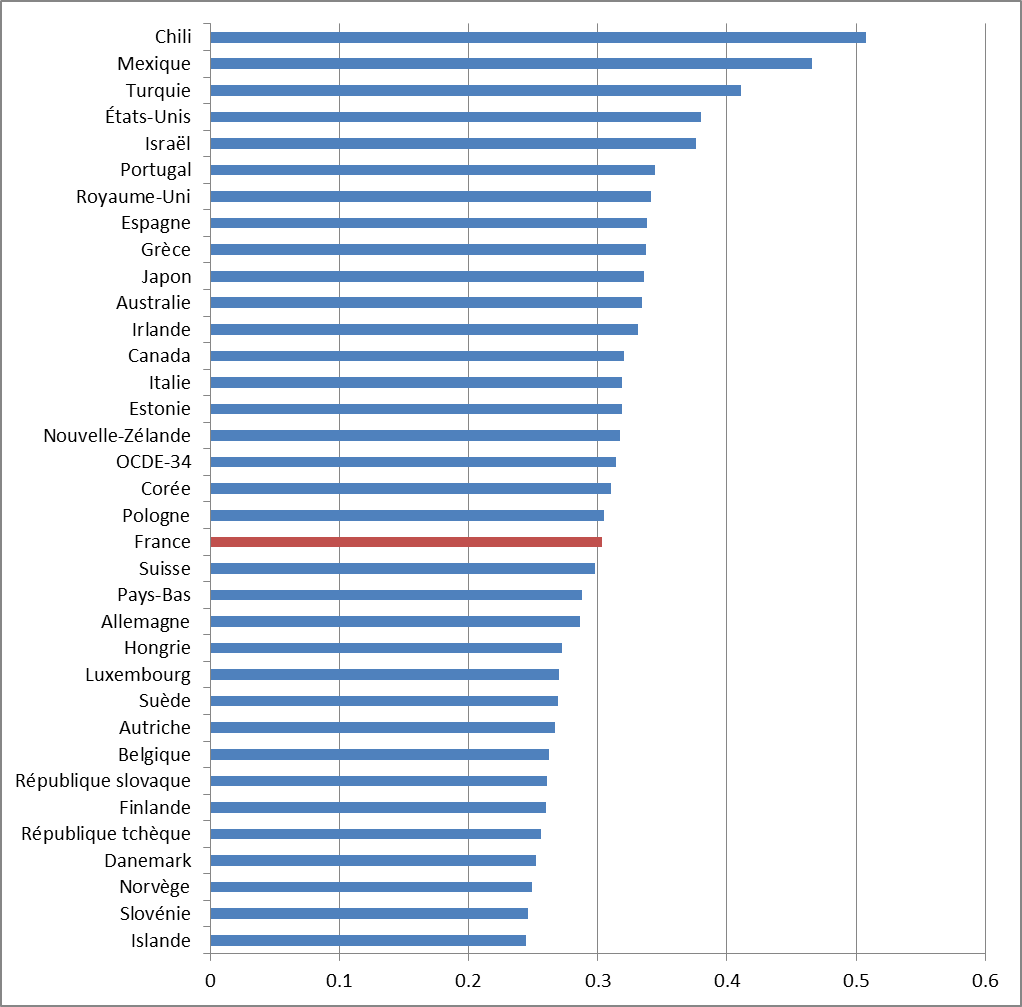

It is widely believed that France stands out from other countries due to its very low level of economic inequality. In reality, when we look at the data available for OECD countries, we see that the situation in France is not so favorable (see Figure 1). In terms of income inequality measured by the Gini coefficient after taxes and transfers[1], France ranks around the average for OECD countries. In 2010, its level of inequality was certainly lower than that of Anglo-Saxon countries (the United States, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand), but it remained higher than that of a number of countries, including the Scandinavian countries (Norway, Sweden, and Finland), certain Eastern European countries (the Czech Republic, Slovenia, and Slovakia), and some of its geographical neighbors (Germany and the Netherlands).

Figure 1: Gini coefficient after taxes and transfers in 2010

Note: The year is 2009 for Hungary, New Zealand, Ireland, Japan, Turkey, and Chile. Sources: OECD, BSi-Economics

These differences in levels can be explained in part by the type of society « desired « by citizens. Anglo-Saxon countries, for example, are characterized by a desire to promote individual effort, which translates into significant income disparities. Conversely, Scandinavian countries are known for their desire to have a narrow income distribution scale and significant redistributive policies. France lies halfway between the Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian models in terms of inequality. While effort should be rewarded, the inequalities it generates are greatly reduced by our tax system.

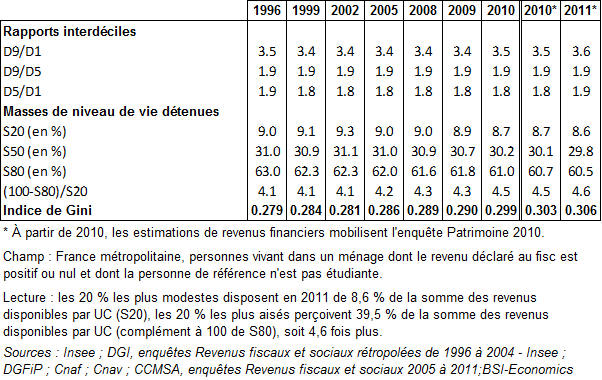

Beyond the level of inequality in France compared to other OECD countries, it is important to look at the broader trends. According to the Gini coefficient or the indicator (100-S80)/S20[2], the level of inequality in living standards remained stable between 1996 and the mid-2000s (see Table 1). From 2005 to 2011, inequality increased steadily, returning to its 1980 level (Fremeaux and Piketty, 2013). According to the D9/D1 interdecile indicator[3], the increase is more recent, beginning between 2009 and 2010. However, the important thing is not to know the exact start of this upward trend, but to understand the repercussions it may have on our society. We must therefore consider the potential effects of inequality on the well-being of the population.

Table 1: Indicator of inequality in living standards between 1996 and 2011

According to conventional wisdom, economic inequality is a source of growth

According to the classical approach, a high level of economic inequality is good for society. Inequality provides a strong incentive for innovation, thereby promoting economic growth. According to this approach, individuals are willing to innovate, invest, and work hard if they can subsequently benefit from substantial income. Inequality is therefore simply the result of rewarding prior efforts. From this perspective, inequality lifts society as a whole.

Another argument, also based on classical theory, can also be used to justify inequality. This is the marginal propensity to save, which increases as income rises. Thus, when wealthy people receive additional income, they save more than if the same level of additional income had been distributed to people with modest incomes. This is because people at the bottom of the income distribution scale will spend the additional income on increasing their consumption in order to meet their needs. Only when they reach a sufficiently high standard of living will they be able to start saving the additional income. The ability of wealthy individuals to increase the available stock of savings reduces borrowing costs and thus promotes investment through lower interest rates. This mechanism will create economic growth and benefit everyone. In this way, inequality creates situations where certain individuals earn enough income to save a portion of it and finance investments, all other things being equal.

This approach is challenged by the adverse effects of inequality on society.

While these two justifications may seem appealing, economists find it difficult to reach a consensus on the effects of inequality on economic growth. Some studies find that the effect between the level of inequality and economic growth is positive (Forbes, 2000), while others conclude that it is negative (Barro, 1999) or that there is an inverted U-shaped relationship, without defining a threshold (Banerjee and Duflo, 2003). In addition, two researchers from the International Monetary Fund put forward the idea that high levels of inequality were one of the causes of the 1929 and 2008 crises in the United States (Kumhof and Rancière, 2010). Based on empirical observations and a theoretical model, the authors show that the rise in inequality that led to high levels of inequality just before the onset of the two crises is one of the reasons for their outbreak. According to their model, rising inequality leads wealthy individuals to lend more and more money to low-income individuals, thereby driving the development of the financial system. In this way, individuals at the bottom of the ladder can continue to consume while their debt-to-income ratio increases dramatically. Granting loans to households in increasingly fragile situations and the development of banking intermediation can weaken the financial system and lead to the outbreak of crises such as those of 1929 and 2008.

Beyond purely economic effects, economic inequality can have negative repercussions on certain social aspects and thus limit countries’ development (Thorbecke and Charumilind, 2002). First, there appears to be a positive relationship between the level of inequality and crime. G. Becker, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics, was the first to highlight this relationship in 1968 (Becker, 1968). Subsequently, many authors have empirically tested this relationship by controlling for endogeneity risks and have found a positive effect (Fajnzylber et al. 2002a 2002b). In the economic approach to crime, individuals are rational and weigh the costs and benefits of working legally versus being a criminal (an article on the link between economics and crime was published on BSi). The greater the inequality, the higher the potential income from criminal activity. In this case, it becomes advantageous to be a criminal.

The level of pollution emissions also appears to be positively correlated with inequality (Boyce 1994 and Boyce and Torras 1998). Indeed, inequality results in a greater share of income from economic activity being captured at the top of the income distribution scale. Furthermore, it is economic activity that generates this income. Thus, when inequality increases, those at the top of the distribution scale receive more income and have no interest in reducing the economic activity that generates pollution. They will therefore use all their influence to lobby politicians to limit restrictive environmental standards as much as possible.

The choice to invest in education can also be undermined when inequalities aresignificant and there is strong social reproduction between generations (Bourguignon et al. 2007). In this situation, people at the bottom of the income scale may believe that they will never be able to achieve a higher social status because there is little mobility. They therefore have no motivation to invest in education.

Finally, it would appear that inequality can lead to greater political instability (Alesina and Perotti 1996). This approach is based on the theory of relative deprivation, according to which people with low incomes are frustrated that they cannot live as comfortably as those at the top of the distribution scale. This feeling then leads to violent collective political action on the part of the discontented (Muller 1985).

Conclusion

Although relatively moderate, economic inequality in France has been steadily increasing since the mid-2000s. This trend may be desirable if it leads to improved living conditions for the entire population. However, we have just seen that the positive effects of inequality on economic growth are far from certain. On the contrary, it would appear that a high level of inequality can lead to a risk of economic crisis, a deterioration in a country’s environment and education standards, and an increase in crime and political instability. For these reasons, it is essential to fully understand the issues surrounding inequality and to limit its increase as much as possible.

References:

– Alesina A. and Perotti R., 1996, Income Distribution, Political Instability, and Investment, European Economic Review, Vol. 40, No. 6, pp. 1203-1228

– Banerjee A. V., Duflo E., 2003, Inequality and Growth: What Can the Data Say?, Journal of Economic Growth, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 267-299

– Becker G, 1968, Crime and punishment: an economic approach, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 76, pp. 169-217

– Bourguignon F., Ferreira F. H. G. and Walton M., 2007, Equity, Efficient and Inequality Traps: A Research Agenda,The Journal of Economic Inequality, Vol. 2005, No. 2, pp. 235-256

– Boyce J. K and Torras M., 1998, Income, inequality, and pollution: a reassessment of the environmental Kuznets Curve, Ecological Economics, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 147–160

– Boyce J.K., 1994, Inequality as a cause of environmental degradation, Ecological Economics, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 169–178

– Fajnzylber P., Lederman D. and Loayza N., 2002a, What causes violent crime?, European Economic Review, Vol. 46, No. 6, pp. 1323-1357

– Fajnzylber P., Lederman D., and Loayza N., 2002b, Inequality and Violent Crime, Journal of Law & Economics, Vol. 45, No. 1, pp. 1-40

– Fremeaux N. and Piketty T., 2013, Report on growing inequalities and their impacts in France, 137 p.

– Fobes K., 2000, A Reassessment of the Relationship Between Inequality and Growth, American Economic Review, Vol. 90, No. 4, 869-887

– Kumhof M., Rancière R., 2011, Inequality, Leverage and Crises, CEPR Discussion Papers, Number 8179

– Lévêque C., 2012, Crime and Economics, BSI-Economics

– Muller E. N., 1985, Economic inequality, regime spresiveness and political violence, American Sociological Review, Vol. 53, No. 1, pp. 56-68

– Thorbecke E. and Charumilind C., 2002, Economic Inequality and Its Socioeconomic Impact, World Development, Vol. 30, No. 9, pp. 1477-1495

Notes:

[1]The Gini coefficient is an indicator used to measure income dispersion within a society. It ranges from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (perfect inequality).

[2] This indicator measures the share of disposable income per consumption unit held by the richest 20% compared to that held by the poorest 20%. If the indicator increases, it means that inequality is growing.

[3] The D9/D1 interdecile ratio measures the ratio between the standard of living of the richest 10% (lower limit) and the poorest 10% (upper limit). In 2010, the richest 10% had a standard of living 3.6 times higher than the poorest 10%.