Summary:

– Public-private partnerships (PPPs) involve delegating the management of a public service to a private company. There are many different forms of PPP, which vary depending on the involvement of the private provider.

– Private companies can take advantage of more techniques and incentives to reduce their production costs. However, they do not seek to maximize social surplus but rather profit. This is why delegating a public service has an indeterminate effect on social surplus.

– In the case of water in France, private providers charge higher prices than public distributors. However, it is the cities facing the greatest technical difficulties that call on private providers.

– A simple comparison of prices in cities where water distribution is outsourced to a private company and those where distribution is managed by a public body shows that the price difference is overestimated.

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) are forms of collaboration between a private company and a public body in which a public service or infrastructure is delegated, at least in part, to a private provider. These organizational models are often advocated by international organizations (in the case of water, the World Bank, for example, pointed out the inefficiency of public providers duringthe International Decade for Clean Drinking Water (1981-1990) and encouraged the creation of PPPs in developing countries) and appear to be an interesting way of limiting the weight of the public sector in the economy (and thus possibly reducing public debt). However, the question arises as to whether these partnerships are effective and how their effectiveness can be assessed. This question raises several difficulties.

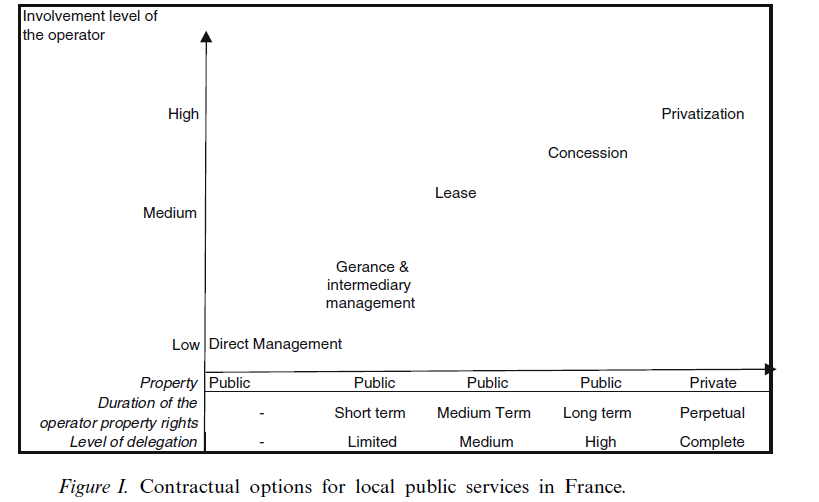

First, there are many different types of PPPs depending on the involvement of the private provider in the management of the public service (management, leasing, etc.). This heterogeneity makes it difficult to evaluate PPPs as a whole.

A second difficulty stems from the fact that, in order to measure the effectiveness of a PPP, it is not enough to compare the cost of a service where it has been delegated to a private provider and where it is produced directly by a public body. Such a comparison would overlook the fact that the reasons for delegating the public service may also impact its cost.

Public-private partnerships in water management and distribution in France provide an interesting practical case. This service is usually controlled at the municipal level, which allows for empirical investigations (quantitative estimates) of the efficiency of services offered by PPPs with large samples (containing sufficient observations).

Furthermore, despite the wide variety of contracts, « leasing » contracts, in which private operators are responsible for maintenance investments and day-to-day management, are the most common. It is therefore possible to measure the effectiveness of these contracts, and it would appear that these partnerships are not usually associated with an increase in water prices in France.

The debate surrounding PPPs

The debate surrounding PPPs does not only concern water management and distribution, and it is worth pausing for a moment to consider it. PPPs involve delegating a public service to a private company. There are, of course, several forms of delegation, with varying degrees of involvement by the private operator. Since this is a public service, the most common objective is to maximize « social welfare. » It may therefore seem strange to delegate this service to a private company, which may favor maximizing its profits at the expense of the public interest.

This delegation is justified by the fact that private companies can be more efficient than a public provider due to lower production costs achieved in two ways:

– Better cost control: since the company’s objective is to maximize profit, it will most often seek to minimize its production costs. A public provider may have slightly different incentives; for example, a civil servant may have an interest in heading up the largest possible service, which can lead to overstaffing or overinvestment.

– Economies of scale: A private provider can operate on a much larger scale than its public counterpart. In the case of water, a supplier can operate on a national scale, while a municipality will be limited to the local level. The operator will therefore be able to make investments that would not be profitable at the municipal level, which can lead to significant cost reductions for the entire network.

Here, the criterion of efficiency is based on minimizing production costs. Indeed, in the case of water, where quality is set exogenously (in the case of water, for example, the government sets the maximum concentrations of chemical elements allowed per milliliter of water), this objective of maximizing well-being is often very similar to that of minimizing the price of a service (to achieve the required level of quality). This is why, although price is not the only dimension of service quality, studying price can, in the case of water, be a sufficient approximation.

However, minimizing costs does not necessarily go hand in hand with lower prices for consumers. Private companies can reduce their intermediate costs but increase their margins. Even when the final price to consumers is determined in advance through a PPP delegation contract, consumers may be disadvantaged if the company imposes excessively high prices due to insufficient competition in its market. Furthermore, once the delegation has been made, it is often difficult and costly to return to public management or change private service providers, which could lead to abusive renegotiation of rates by private service providers. This is why France has a legal arsenal that normally guarantees that bargaining power remains effectively in the hands of local authorities. Despite these legal protections, it turns out that PPPs are not always profitable.

Figure 1 – Possible types of contracts (from Chong et al. 2006)

PPPs and water management in France: often ineffective delegation

The simplest way to assess the effectiveness of PPPs would be to compare the price of water in municipalities (where water management has been entrusted to a private organization) with the price in cities where water management remains under public control. This comparison highlights a significant difference in the prices charged by public providers and private companies: on average, private companies charge €26 more for 120 cubic meters of water (according to Chong et al. 2006). However, this method has a major methodological problem that leads to an overestimation of this difference.

A direct comparison between cities that outsource water management and those that do not would lead us to overlook the fact that the choice to outsource is a decision made by the cities themselves. In econometric terms, they self-select into the treatment whose impact we wish to study (in this case, outsourcing water distribution to a private provider). The problem is that the reasons for this choice may themselves influence the price of water. For example, major technical difficulties in water distribution will naturally have an impact on the final price, but may also lead a municipality to call on a private service provider.

In this case, the choice to delegate will be based on production difficulties: cities whose water distribution does not present any difficulties will not delegate, while those for which the operation is delicate will opt for delegated management. It is therefore understandable why a direct comparison leads to biased results: private and public operators do not face the same conditions.

Several econometric methods can be used to get around this difficulty (IV, Treatment Effect Model, Switching Regression, etc.), the general idea being to model directly the fact that the choice to delegate did not occur by chance.

Two articles from 2006, Chong et al. and Carpentier et al., apply these methods and compare the price of water when the management of this public service is delegated to a private company (most often through leasing contracts) or when the municipality takes direct responsibility for it. Although they use different techniques, the two articles offer three similar conclusions:

- Cities facing significant technical difficulties are more likely to delegate water distribution.

- A direct comparison therefore skews the impact of private management on price upwards.

- Once this effect is corrected, private providers remain more expensive than public providers.

In other words, PPPs would be inefficient here, but less so than they would appear if we directly compared the final prices of services. Thus, of the €26 difference found by Chong et al. (2006), only €11 would constitute actual overcharging. Similar results were found in Germany (Ruester and Zschille, 2010) and Spain (Martinez-Espineira et al., 2009). France is therefore not an isolated case. However, there is still little or no explanation for the mechanism leading to this difference between private and public operators. Can it be attributed to the profit-maximizing behavior of private operators, or is it due to a lack of ex-ante competition? These are questions that researchers must now address.

Conclusion:

The question of whether or not to use PPPs must often be resolved on a case-by-case basis. Due to productive advantages and better incentives, private companies can often produce public services at a lower cost than public operators. On the other hand, there is no guarantee that this productive efficiency will be reflected in the final price.

In France (and Western Europe), the decision to delegate distribution leads to paradoxical results. When water distribution is complicated, French cities favor delegation to private providers, but this delegation leads on average to higher prices (even once these technical difficulties are taken into account). PPPs are therefore less efficient than direct management by cities.

Reference

– Chong, Huet, Saussier, and Steiner, Public-Private Partnerships and Price: evidence from water distribution in France, Review of Industrial Organization (2006)

– Alain Carpentier, Céline Nauges, and Arnaud Reynaud Alban Thomas, Effects of delegation on the price of drinking water in France: An analysis based on the literature on « treatment effects, « Economie et prévision 2006.

– Roberto Martínez-Espiñeira, Maria A. García-Valiñas, and Francisco J. González-Gomez, Does private management of water supply services really increase prices? An empirical analysis, urban studies 2009.

– Sophia Ruester and Michael Zschille,The Impact of Governance Structure on Firm Performance: An Application to the German Water Distribution Sector, working paper, 2010.

Additional notes dated February 3, 2014:

Stéphane Saussier, one of the authors of the article Public-Private Partnerships and Price: evidence from water distribution inFrance cited above, has referred us to a more recent working paper (Chong et al. 2012)in which he continues the analyses developed above. BSI Economics thanks him for this comment and we take this opportunity to present some of his findings.

The first result confirms the findings of previous studies. Using a new method and a different sample (of approximately 3,500 municipalities of all sizes observed in 1998, 2001, 2004, and 2008), the authors obtain results very similar to those of their previous study: standard OLS predict a price difference of €27, when the true difference (once the endogeneity problem is resolved) would be €11. Once again, private providers are more expensive than public providers.

The authors also refine this analysis by specifying that the price difference would only be significant for cities with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants. Large cities would only pay an additional €4, which is insufficient to conclude that there is a real difference.

Where does this difference come from? Intuition and economic theory can give us a clue: the bargaining power of cities when negotiating with private providers, as well as the incentives for private providers not to impose excessive price increases (once the contract is signed), depend onthe cities’outside option . That is, their situation if they chose another private provider or if they decided to distribute water themselves. Large cities are much more attractive to private providers than smaller ones, and they are also capable (for reasons of scale, for example) of supplying themselves. These two points suggest that a large city will have greater bargaining power since competition between private providers will be greater and, even if competition is not strong, the provider must take into account the possibility that the city will supply itself.

The authors test this mechanism in part by analyzing the factors that influence the probability of renewing a private provider’s contract. They show that large cities react to a potential cost overrun by a private provider (defined as the percentage difference between the price actually paid and the price the city can expect to pay) by reducing the probability of renewing the contract, while small cities do not. The threat of sourcing elsewhere would therefore be credible for large cities, which would discipline private actors and reduce their prices.

Eshien Chong, Stéphane Saussier, Brian S. Silverman, Water under the Bridge: City Size, Bargaining Power, Prices and Franchise Renewals in the Provision of Water, Working paper, May 2012.