This month, the ECB began its asset purchase program by buying the famous « covered bonds. » Will these asset purchases automatically lead to a direct increase in the money supply equal to the amount of the purchases (as has sometimes been suggested)? Will $500 billion in ABS and covered bond purchases result in $500 billion in money creation? Not really. Without further details, this is not valid. Asset purchases will result in a direct mechanical increase in the money supply only if the assets are purchased from entities that are not banks. Otherwise, the direct mechanical implication will be an increase in the monetary base only in the very short term [1]. Explanations.

How does the money supply increase? We have already answered this question in a previous insight (link here). Every time bank deposits are created, money is created. Every time they are destroyed (and not replaced by another component of the money supply), money is destroyed. Do the ECB’s asset purchases automatically result in an increase in bank deposits? Not necessarily. There are two possible scenarios.

1) If the ECB buys assets from banks, there is no automatic increase in the money supply as a result of the transaction. The money supply is unaffected by the transaction, as we can see in the diagram below:

Scenario 1: purchases of securities from banks

The ECB purchases an asset from a bank. The ECB pays with cash. On its balance sheet, the bank no longer has an « ABS » asset but new cash. Bank liquidity (or « reserves ») has increased overall as a result of this transaction. Bank liquidity is an integral part of the monetary base, but not of the money supply: the monetary base has increased and the money supply has remained unaffected by the transaction.

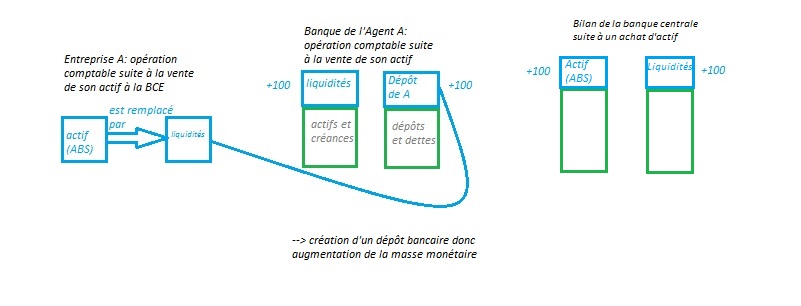

2) If the ECB buys assets from non-bank agents (excluding the government), there is a mechanical increase in the money supply via the transaction. This is directly affected by the transaction, as we can see here:

Scenario 2: purchases of securities from financial companies

The ECB purchases an asset from a non-bank financial institution (investment fund, insurance company, etc.) or a household. The ECB pays with cash. It will pay by crediting the bank account of the non-bank company in question. On its assets side, the financial company no longer has an « ABS » asset but new cash in its bank account. Bank deposits have therefore increased overall through this operation. Thus, the money supply has increased (as has the monetary base) with the operation.

We can therefore see that the ECB’s asset purchases will not automatically result in a direct increase in the money supply by the same amount. It all depends on the counterparties chosen for the ECB’s purchases. This is what leads some, such as Patrick Artus, to differentiate between QE involving « purchases from households and businesses » and other forms of QE where the counterparties potentially include banks (see link here). He argues that the first type of QE could be more effective. For others, such as BIS economists Claudio Borio and Peter Disyatat, the distinction is irrelevant in a general framework (see link here): « whether the asset is initially bought from the non-bank public or not makes little difference to the final outcome in terms of the equilibrium amount of deposits, the relative yields on assets, and funding conditions. » The question of the effectiveness of QE depending on the counterparty chosen for the purchase goes beyond this insight. What is certain, however, is that in the medium term, the mechanical increase in the money supply due to the ECB’s asset purchases is necessarily less than the total amount of asset purchases. The reason for this is that, in case 2) presented here, portfolio adjustments will take place following changes in asset prices: securities will move from banks to households and businesses.

Julien Pinter

Related articles of interest:

« Money creation in the modern economy,« Bank of England (link here)

« Unconventional monetary policies: an appraisal,« Bank for International Settlements (link here)

Notes:

[1] This post deals solely with the direct effect mechanically associated with asset purchases: indirect effects on money creation, i.e. those resulting from possible wealth effects or a possible revival of credit following asset purchases at a later stage, are not covered in this post.