Abstract :

- Despite notable progress, women remain underrepresented among elected officials.

- Gender appears to play a role in public policy decision-making, particularly in terms of public investment.

- At the central bank level, greater female representation is associated with lower inflation.

- Countries where women are most represented are mostly at the top of the global rankings in terms of governance, income inequality, and public spending (R&D, education), i.e., economic variables directly linked to the implementation of public policies.

- Elected women serve as role models for women in the countries where they hold power.

Although women remain underrepresented in parliaments and governments overall, more and more women are emerging as heads of government, such as Indira Gandhi in India in the 1960s-1980s, or more recently Jacinda Ardern in New Zealand and Mette Frederiksen in Denmark.

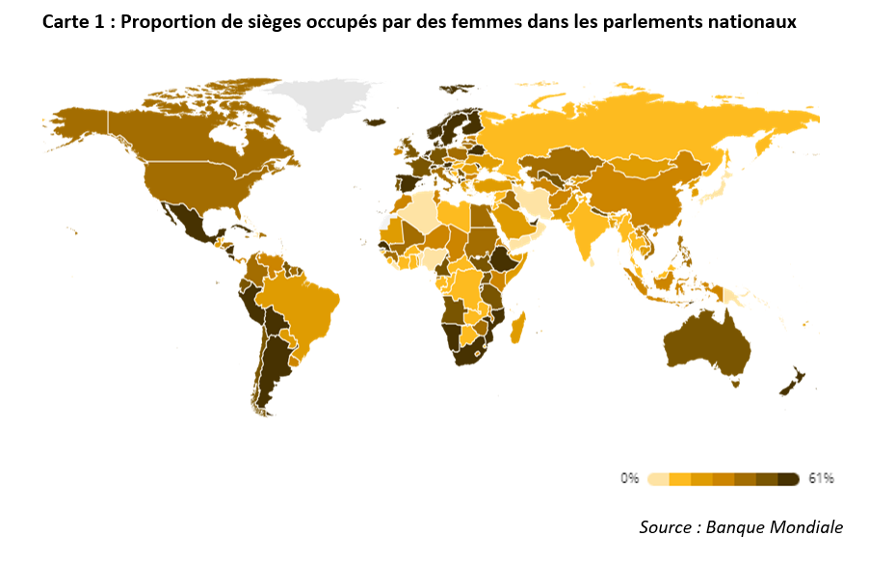

In 2022, women held an average of 26.5% of seats in parliaments worldwide, compared to 19.2% in 2010. Nordic countries such as Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark, and Iceland stand out in this regard, with particularly high rates of representation exceeding 45% (Map 1). Is this simply a stylized fact or does it have real economic implications? It would appear that the gender of political leaders is not insignificant, whether in terms of public policy decision-making or in the way these policies are implemented and perceived.

Gender clearly plays a role in public policy decisions

The association between gender and its impact on public policy is based on the fact that men and women have different political beliefs, social preferences, and social ethics. In this sense, it has been shown in Switzerland, in particular, that women are more altruistic and more concerned with issues of social justice and access to public services (Funk and Gathmann, 2006).

In this regard, Chattopadhyay and Duflo (2004) found that an increase in women’s participation in political life in Indian villages led to a significant increase in spending on public infrastructure, particularly in terms of drinking water supply. To establish a causal effect, the authors used the introduction of a quota in village councils in West Bengal and Rajasthan. The study by Beaman et al. (2012), also based on this event, tends to show that greater representation of women in municipal councils leads to increased investment in children’s education and health. From an aggregate perspective, Baskaran et al. (2018) suggest that Indian constituencies subject to quotas perform better in terms of economic growth and levels of corruption than others. These differences in corruption are probably linked to the findings of Grosh and Brau (2017), which show that women tend to be more honest than their male counterparts.

The findings are similar in developed countries: Besley and Case (2003) find that greater representation of women in US state legislatures increases public spending on family support programs, while strengthening the enforcement of child support laws. Finally, elected women have a positive and significant average impact on the implementation of policies related to women themselves, particularly those related to maternity leave or abortion rights in OECD member countries (Kittilson, 2008).

From the central bank’s perspective, a higher proportion of women on monetary policy committees contributes to lower inflation rates in nine OECD countries (Farvaque et al., 2011). Lower inflation generally has a positive effect on macroeconomic balances and is consistent with the mandate of central banks. The gender factor therefore appears to be positive in contributing to greater economic and financial stability. According to Farvague et al., once appointed, women must be even more « conservative » than their male counterparts in order to maintain their credibility within the committee in question. This finding seems to suggest that there may be an unfavorable gender effect here. The credibility of a central bank depends on the effective use of its tools to achieve the objectives set out in its mandate. If the lack of recognition of female members of monetary committees pushes them to be overly « conservative, » this can lead to monetary policies that are also overly « conservative. » The risk here is that an overly « conservative » monetary policy could unnecessarily weigh on economic and financial stability and even ultimately undermine the credibility of the central bank.

However, contrary to popular belief that women would have handled the COVID-19 episode better, no difference in crisis management could be identified between male and female leaders (Aldrich and Lotito, 2020).

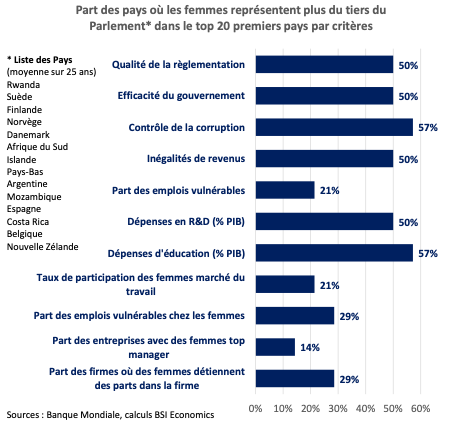

The 14 countries where women account for more than a third of the seats in parliament tend to be among the best countries on a range of public policy criteria (see chart below). This is particularly true for developed countries, especially on governance criteria established by the World Bank (quality of regulation, government efficiency, control of corruption).. While it is difficult to draw any real conclusions from these correlations, they do allow us to observe where countries seem to have an arsenal of effective public policies to address certain issues and where these policies need to be designed and implemented more efficiently.

While a majority of the 14 countries score relatively well on certain economic criteria (income inequality, R&D and education spending as a percentage of GDP), only four (the Northern European countries excluding Finland) have succeeded in implementing particularly effective public policies to combat job vulnerability (the situation is similar for women’s employment). It is also interesting to note that the integration of women into business life is particularly widespread among those 14 countries with a relatively higher proportion of women elected to parliament. The results here are rather disappointing. Contrary to popular belief, it is often emerging countries that have particularly high ratios, regardless of the representation of women in parliament: Sub-Saharan African countries in terms of women’s participation in the labor market; a majority of Eastern European and Central Asian countries in terms of the proportion of companies with women in top management; and a small majority of Latin American countries (plus France!) with a higher proportion of women who hold shares in their companies. However, in some cases, this representation can be explained by a policy known as « purplewashing, » in the sense thatthedecision-making impact of women in the political bodies in question is sometimes virtually nil.

In short, exposure to female politicians can have a significant effect on how voters perceive women and how women perceive themselves. Wolbrecht and Campbell (2007) have shown that in countries where the proportion of female parliamentarians is higher, teenage girls and adult women are more likely to participate in politics. In India, for example, exposure to female political leaders also encourages teenage girls to become more ambitious in terms of education (Beaman et al., 2012).

In this sense, Perrin (2023) shows that a female head of government tends to encourage women to start their own businesses. Indeed, exposure to women in positions of power allows women to identify with and be inspired by them. In addition, the presence of female heads of government increases the likelihood of reducing inequalities in terms of rights, allowing women to gain autonomy and choose their professional careers. Similarly, more women appointed to municipal councils in India increases the proportion of women engaged in the labor market. Finally, women’s access to political power has long-term effects on them: De Paola et al. (2010) show that Italian municipalities that have been subject to quotas in the past elect a higher proportion of women as mayors, even after the quota in question has been abolished.

However, given the limited number of women leaders, it remains difficult to identify robust causal links with regard to the policies implemented in the countries concerned. Indeed, the probability of a woman becoming head of government depends heavily on a country’s level of development and the quality of its institutions (Jalalzai, 2013). In short, a selection process takes place during the electoral process, with the result that female candidates have many similarities with male politicians and are not representative of the average woman (Schwindt-Bayer, 2011). It therefore remains difficult to generalize these conclusions.

References:

Aldrich, A., & Lotito, N. (2020). Pandemic Performance: Women Leaders in the COVID-19 Crisis. Politics & Gender, 16(4), 960-967.

Baskaran, T., Bhalotra, S., Min, B., & Uppal, Y. (2018). Women legislators and economic performance. WIDER Working Paper 2018/47.

Beaman, L., Duflo, E., Pande, R., & Topalova, P. (2012). Female leadership raises aspirations and educational attainment for girls: A policy experiment in India. Science, 335(6068), 582-586.

Besley, T., & Case, A. (2003). Political institutions and policy choices: evidence from the United States. Journal of Economic Literature, 41(1), 7-73.

Chattopadhyay, R., & Duflo, E. (2004). Women as policy makers: Evidence from a randomized policy experiment in India. Econometrica, 72(5), 1409-1443.

De Paola, M., Scoppa, V., & Lombardo, R. (2010). Can gender quotas break down negative stereotypes? Evidence from changes in electoral rules. Journal of Public Economics, 94(5-6), 344-353.

Farvaque, E., Stanek, P., & Hammadou, H. (2011). Selecting your inflation targeters: Background and performance of monetary policy committee members. German Economic Review, 12(2), 223-238.

Funk, P., & Gathmann, C. (2006). What women want: Suffrage, gender gaps in voter preferences and government expenditures. Gender Gaps in Voter Preferences and Government Expenditures (July 2006).

Grosch, K., & Rau, H. A. (2017). Gender differences in honesty: The role of social value orientation. Journal of Economic Psychology, 62, 258-267.

Jalalzai, F. (2013). Shattered, cracked, or firmly intact?: Women and the executive glass ceiling worldwide. Oxford University Press.

Kittilson, M. C. (2008). Representing women: The adoption of family leave in comparative perspective. The Journal of Politics, 70(2), 323-334.

Perrin, C. (2023). You’re the One That She Wants (To Be)? Female Political Leaders and Women’s Entrepreneurial Activity. SSRN (June 2, 2023).

Schwindt-Bayer, L. A. (2011). Women who win: Social backgrounds, paths to power, and political ambition in Latin American legislatures. Politics & Gender, 7(1), 1-33.

Wolbrecht, C., & Campbell, D. E. (2007). Leading by example: Female members of parliament as political role models. American Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 921-939.

[1]An overly « conservative » monetary policy, consisting, for example, of raising key interest rates too high and too often, can lead to overly tight financing conditions and generate more economic and financial instability than desired (risk of recession, liquidity risk, vulnerability risk linked to public and/or private debt, etc.).