Abstract:

- The number of job vacancies in France has grown significantly in the post-lockdown period, mainly due to the increasing difficulty companies are having in filling previously occupied positions.

- This resurgence of tensions in the labor market can be explained by a general mismatch between supply and demand in a context of economic recovery, but seems to affect certain sectors suffering from a lack of attractiveness more particularly;

- However, these recent developments should not overshadow the structural dimension of labor shortages in the French economy, which seem to undermine the assumption of a return to normal once the economic cycle begins to turn around.

« There is nothing more ‘Shadockian’ than still having so much unemployment and so many companies looking for employees, »[1]said Bruno Lemaire at the Rencontres économiques d’Aix-en-Provence in the summer of 2022. The Minister of Economy and Finance then placed the issue of labor shortages as Bercy’s second priority after purchasing power.

This statement must be put into context. Between the first quarter of 2021 and the fourth quarter of 2022, the number of job vacancies in France in companies with more than 10 employees (in other words, the number of unfilled jobs) rose from 224,435 to 390,822 (+74%). This is a record high for the last two decades.

Even more surprising is that the number of job vacancies remained at 367,536 in the second quarter of 2023. This figure is down from the peak reached at the end of 2022 but still considerably higher than its pre-pandemic level, even though the economy has been slowing down since the beginning of the year, driven by tighter financing conditions and declining purchasing power.

This note will explore the cause(s) of this phenomenon and distinguish between its cyclical and structural dimensions.

1. A cyclical phenomenon?

The French economy has seen a surge in job vacancies since the beginning of 2021, a period marked by the lifting of strict lockdowns and the start of the national vaccination campaign. Against a backdrop of strong and rapid economic recovery (French growth was +6.8% in 2021 after a fall of -7.8% in 2020), labor demand rose sharply without being fully matched by directly available resources.

The sustained increase in job vacancies in the post-lockdown period must be compared with the increase in total jobs in order to assess the real extent of the labor shortage. Indeed, if jobs as a whole had increased more than job vacancies over the same period, the job vacancy rate[2] would then be declining. However, Figure 1 shows that the growth in job vacancies has indeed exceeded that of total employment in the economy. It should be noted that a slight decline in the vacancy rate, parallel to that observed in the aggregate job vacancy data, has been visible since the end of 2022, a sign that the economic slowdown is beginning to have a moderate impact on the job market.

Sources:Dares (Acemo), INSEE

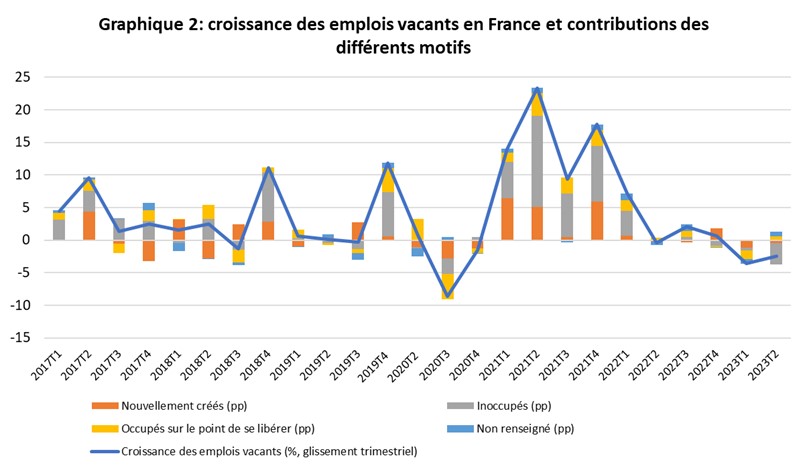

In order to gain an accurate picture of the phenomenon, it is also necessary to look at the reasons for these job vacancies. The increase in unfilled jobs can be explained by a variety of causes reflecting different dynamics in the labor market. In its survey entitled « Activity and Employment Conditions of the Workforce » (Acemo), the Directorate for Research, Studies and Statistics (Dares), attached to the Ministry of Labor, breaks down job vacancies into three main categories:

- Vacancies resulting from newly created but as yet unfilled positions. These may indicate a healthy job market and economic activity, with significant new job creation to meet new needs.

- Vacancies resulting from unfilled positions, where the previous occupant has left without a replacement being found. These unfilled vacancies are more worrying in that they reflect an inability to fill existing positions for various reasons (low attractiveness, lack of skilled labor, etc.);

- Vacancies resulting from positions that are currently occupied but are about to be vacated by their current occupants. This category is particularly useful for observing potential waves of resignations on a macroeconomic scale.

Figure 2 below shows the growth in job vacancies broken down into these three categories. It is immediately apparent that the strong growth in job vacancies since the beginning of 2021 is primarily the result of a significant increase in so-called « unfilled » vacancies. While these accounted for an average of 40% of the total stock of job vacancies between 2011 and 2019, this proportion rose to 49% between 2021 and the first half of 2023, showing much faster growth than the other two categories. The labor shortages observed over the past two years therefore seem to be mainly explained by employers’ difficulty in filling previously filled positions.

Source: Dares (Acemo), author’s calculations

One initial explanation put forward for these difficulties in filling positions points to the role of the decline in the working-age population in the economy caused by the pandemic. Due to the temporary interruption of their work and/or fear of contracting COVID-19, a number of workers may have left the labor market altogether and not returned after the economy reopened (particularly workers close to retirement), thus contributing to an imbalance between labor supply and demand. However, Figure 1 shows that this explanation does not hold true in the case of France. Although the labor force participation rate did indeed decline in 2020, it had already returned to its pre-pandemic level by the beginning of 2021 and therefore cannot explain the increase in the job vacancy rate recorded over the following two years. The same is true for workers approaching retirement, as shown by the curve depicting the labor force participation rate of individuals aged 50 to 64.

Another explanation points to a possible decline in the supply of young workers, who are currently in a better bargaining position in a tight labor market, preventing companies from filling their « junior » positions. Once again, this hypothesis does not seem to stand up to the test of the data. According to Figure 1, the employment rate for those under 25, after experiencing a temporary dip in 2020, has improved significantly over the last two years, rising from 30% at the end of 2019 to nearly 35% for the first half of 2023 (helped in particular by the strong growth in work–study contracts). It has even narrowed the gap with the employment rate for individuals over 50, which has itself increased slightly in recent years.

A third, more plausible hypothesis is that of a recent reallocation of the French workforce in terms of sector of activity, made possible by a currently dynamic labor market that encourages changes in career paths. According to this explanation, a number of economic sectors considered unattractive due to their low pay or difficult working conditions have been shunned by workers since the economy reopened, leading to particularly intense recruitment difficulties in these sectors. To analyze this proposal, we can refer to the INSEE’s quarterly economic surveys, which report the proportion of companies experiencing recruitment difficulties for each major sector of the French economy. Figure 3 presents the series for industry and construction, while Figure 4 focuses on market services.

Source: INSEE

One initial observation stands out when looking at the two graphs: the increase in recruitment difficulties for companies is a cross-cutting phenomenon that has affected the vast majority of sectors. This observation reinforces the idea of a macroeconomic imbalance between labor supply and demand during periods of economic recovery, a phenomenon well known in academic literature.

However, a more detailed analysis of sectoral dynamics indicates that, in line with the hypothesis formulated above, certain sectors characterized by relatively low wage levels and/or working conditions considered difficult (long hours, physical intensity) have been more severely affected than others. This is particularly the case, as widely reported in the media, in the accommodation and food services sector, where the proportion of companies experiencing recruitment difficulties increased by more than 30 percentage points between the start of the pandemic and the end of 2022. Administrative and support activities (including security and cleaning services) also experienced a similar increase in recruitment difficulties. In terms of industrial sectors, equipment manufacturing (electrical, electronic, IT, and machinery) was the most exposed to increased recruitment difficulties over the same period. Two sectors with significant recruitment difficulties in recent quarters, construction and transportation and warehousing, stand out because they already had significant recruitment difficulties before the COVID-19 crisis, particularly due to their low attractiveness. In addition, construction is the only sector that did not see its recruitment difficulties decrease in the first half of 2023. The case of these last two sectors suggests that the analysis of labor shortages in the French economy cannot be complete without taking a more structural view of these issues.

2. Structural trends at work

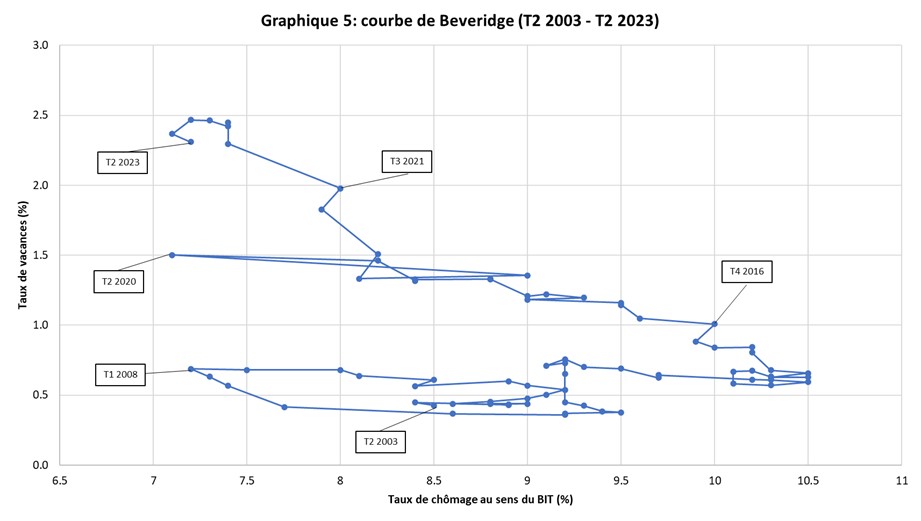

If we were to assume that labor shortages were merely the result of cyclical forces, the phenomenon would appear to be relatively unworrying. The economic slowdown observed in recent months, which is set to continue into 2024, would allow the market to return to a balance of job vacancies by forcing workers to reinvest in less attractive sectors for lack of alternatives. The labor shortage would then have been nothing more than a temporary blip caused by an exceptional macroeconomic shock. However, this reassuring scenario seems at odds with an analysis of longer-term data. Figure 5 below shows a « Beveridge curve » that plots the unemployment rate[6] on the x-axis and the economy’s job vacancy rate on the y-axis for the period from the second quarter of 2003 to the second quarter of 2023.

Sources: Dares (Acemo), INSEE

The points on the curve towards the upper left corner of the graph indicate periods of « tension » in the labor market with low unemployment and a high vacancy rate. Conversely, points on the curve toward the lower right corner generally indicate periods of recession, when the market experiences high unemployment and low vacancy rates because employers have little difficulty filling a small number of positions relative to the number of job seekers. The Beveridge curve, shown above, indicates a major difference in dynamics between unemployment and vacancy rates. While unemployment has fluctuated significantly over the past 20 years in line with economic cycles, the job vacancy rate appears to have been on an upward trend for two decades, rising from less than 0.5% in 2003 to 1% at the end of 2016 and then to 2% in 2021.

There are several explanations for this structural trend:

- A growing disinterest among workers in certain low-paying professions with difficult working conditions (a phenomenon that has been accelerated by the Covid crisis);

- A mismatch between the number of individuals trained in certain professions and the labor needs for those same professions, leading to a shortage of qualified candidates for the positions available;

- Limited geographical mobility among the French population, exacerbated by a gradual decline in the rental market, resulting in significant regional inequalities in terms of access to labor.

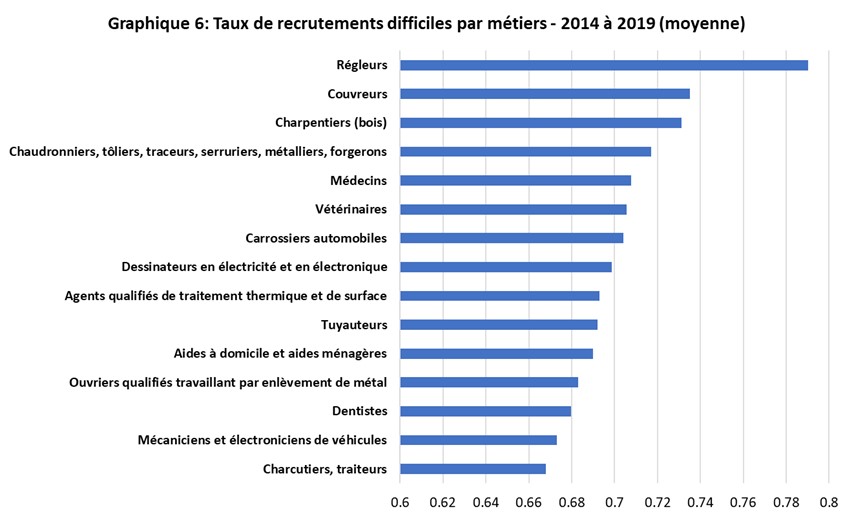

To understand how these structural forces apply in practice to certain professions under pressure, we can look at various examples taken from data in the Pôle Emploi « Labor Needs » survey. Figure 6 below shows the top 15 occupations already facing particularly high rates of recruitment difficulties in the pre-COVID-19 period from 2014 to 2019.

Source: Pôle Emploi

Firstly, it appears that a number of industrial professions (setters, metalworkers, electrical designers, pipe fitters, etc.) have been struggling to recruit candidates for several years now. Paradoxically, estimates made in recent years[9] tend to show that, overall, there is no shortage of trained industrial workers to meet the needs of the sector. However, it seems that a significant proportion (around one-third) of young workers trained in these industrial trades ultimately decide not to pursue the professions for which they were initially trained, contributing to a phenomenon of workforce « evaporation. » But what happens to these young people? A Céreq study conducted in 2023[10] suggests that a significant proportion of them switch to the service sector after completing their training. According to the same study, out of 100 young students trained in fundamental industrial technology professions, 46 of them will, three years after graduating, be employed in non-market services or market services unrelated to industrial activities (information and communication, finance and insurance, household services, etc.). There are several reasons behind this evaporation: (i) a deficient guidance system that pushes young people to train in trades out of necessity rather than choice, but also (ii) a high concentration of industrial trades in certain areas, even though, as mentioned above, the degree of geographical mobility remains limited in France, particularly among workers from the working class[11].

In addition, skilled trades (butchers/caterers, carpenters, roofers) are also experiencing significant recruitment difficulties, particularly due to a lack of sufficiently qualified candidates. At the same time, demand for skilled trades (particularly in the construction sector) shows no sign of abating, given the needs that the environmental transition will create in terms of energy-efficient renovation of housing.

Personal services professions (home helpers and domestic workers) have also been under severe strain for several years now, mainly due to the low attractiveness of these professions (low wages, long working hours, certain tasks considered difficult or « thankless »). Similar to the skilled trades, these shortages, which have been evident for several years, raise questions for the future, given the aging of the French population, which is leading to growing demand for the services offered by these professions.

Finally, certain professions requiring high levels of qualification (doctors, dentists, engineers) as well as so-called « future-oriented » professions (e.g., computer developers, professions specializing in artificial intelligence, etc.) are also experiencing significant recruitment difficulties. While the lack of sufficiently qualified candidates plays an important role in this phenomenon (the case of IT professions requiring the importation of foreign workers is a good example[12]), it is also possible to see, in some cases, the role of the geographical divide and, once again, the reduced mobility of the workforce. In the case of doctors, it is primarily rural areas that suffer most from the shortage of healthcare professionals. According to a 2020 Senate information report, between 9% and 12% of the French population (i.e., 6 to 8 million people) currently live in a « medical desert, » with significant disparities depending on the degree of urbanization of the departments[13]. The document also states that the density of medical professionals in rural areas of France was below the OECD average in 2020.

Conclusion

The vacancy rate has increased significantly since the Covid-19 pandemic due to the growing difficulty companies are having in filling positions left vacant after the departure of a previous employee. Sectors considered unattractive in terms of pay and working conditions (accommodation and catering, low-skilled business services, construction, transport, and warehousing) appear to be the most affected by this phenomenon, in a context of labor market tension favoring career changes.

However, this situation cannot be attributed solely to economic factors. The difficulty certain professions have in recruiting and filling vacancies is a long-standing problem linked in particular to challenges in terms of promoting certain occupations, matching training with the skills required, and the limited geographical mobility of the French workforce. These weaknesses, which have been documented for many years, will not be resolved simply by a reversal of the economic cycle and will require structural reforms in public policy.

The unemployment insurance reforms launched in 2019[14] are a first step, based on incentives for workers and businesses[15]. However, these reforms, which are more cyclical in nature, will certainly need to be complemented by reforms addressing the structural issues raised in this note: educational and career guidance, maintaining a high-quality training offer, facilitating geographic mobility, and improving working conditions in certain professions under pressure.

It would also be interesting, in a future article, to compare the situation in France with that of other developed economies that have also experienced labor shortages over the past two years (the United States, the United Kingdom, and the rest of the eurozone). This work would make it possible to distinguish cross-cutting trends from other effects more specific to the structure of the French economy.

[1]Nathalie Silbert (July 10, 2022), « Labor shortages, Bruno Le Maire’s new ’emergency’, » Les Échos.

[2]The job vacancy rate is defined as the ratio of job vacancies to total existing jobs in the economy.

[3]Pizinelli and Shibata (2022), « Why Jobs are Plentiful While Workers are Scarce? », IMF Blog.

[4]Alain Ruello (February 1, 2023), « Apprenticeships set a new record in 2022, » Les Échos

[5]See in particular: Shimer (2005), « The Cyclical Behavior of Equilibrium Unemployment and Vacancies, » American Economic Review, Vol. 95, No. 1.

[6]The unemployment rate discussed in this note is measured according to the methodology of the International Labor Office (ILO). This is also the measure used by INSEE in its quarterly analyses.

[7]High level after the great financial crisis of 2007-2008 and then the sovereign debt crisis in the euro zone. Lower level before the financial crisis and also after the Covid-19 pandemic.

[8]Guillaume de Calignon (December 15, 2016), « Three ways to reform real estate taxation and encourage geographic mobility, » Les Échos.

[9]Basset and Luansi (2023), « Skills shortage and reindustrialization: a surprising paradox, » La Fabrique de l’Industrie.

[10]Céreq (2023), « Integration of secondary school leavers: vocational training remains an asset, » 2020 survey

2020 among the 2017 cohort, Céreq Bref, no. 433, January.

[11]Schmutz, Sidibé, and Vidal-Naquet (2021) « Why Are Low-Skilled Workers Less Mobile? The Role of Mobility Costs and Spatial Frictions, » Annals of Economics and Statistics, 142, 283-304

[12]Théa Ollivier (April 12, 2019), « France, the new El Dorado for Moroccan engineers, » Les Échos Start.

[13]Maurey and Longeot (2020), « Medical Deserts: The State Must Finally Take Courageous Measures! », Senate, Information Report No. 282.

[14]On February1, 2023, these reforms confirmed a 25% reduction in the duration of unemployment benefits, provided that the unemployment rate is below 9% and does not increase by more than 0.8 points over a quarter.

[15]In particular, a bonus-malus system on unemployment contributions aimed at encouraging companies to prefer hiring on permanent contracts.