⚠️Automatic translation pending review by an economist.

Summary:

– The aim of the labor market reform (or labor law) is to improve the functioning of the labor market by promoting permanent employment contracts, for which the conditions and costs of dismissal would be redefined, and by improving access to training.

– For the time being, the labor law appears to be unbalanced, to the detriment of employee security and to the advantage of flexibility for companies.

– In the short term, the macroeconomic context in France and Europe (low but rising growth and virtually zero inflation) is not conducive to this type of potentially recessionary and deflationary reform.

– In the long term, it is not clear that the labor law will reduce the dualism of the labor market in France.

During his speech to the Economic, Social and Environmental Council on January 18, 2016, French President François Hollande announced that a reform of the labor code would soon be undertaken. Led by Labor Minister Myriam El Khomri, the bill was presented to the Council of Ministers on March 24 and has three objectives: to promote hiring on permanent contracts, to facilitate access to training, and to strengthen social dialogue.

Behind each of these objectives are three key drivers: giving companies the flexibility they need to adapt to economic changes, securing employees’ career paths, and overhauling the way labor market regulations work.

1. Content and objectives of the labor law

The issue of social dialogue and the reversal of the hierarchy of standards was the subject of heated debate with the adoption of the Rebsamen law in June 2015 and the publication of the Combrexelles report in September 2015 (two reports by Terra Nova and the Institut Montaigne also received significant media coverage). A few months later, the work of the Badinter Commission (which will be left aside) once again brought the subject of rewriting the Labor Code to the table. The labor law aims not only to leave more room for collective bargaining, but also to give rise to more agreements negotiated directly at the company level. This objective is supported by an increase in the time allocated to union representatives. These company agreements will now have to be approved by a majority (or even validated by a referendum among employees with a 30% union majority threshold).

On the other hand, the elements of the El Khomri reform concerning the conditions and cost of dismissals were introduced without prior consultation. Although they partly replicate measures implemented abroad (criteria for economic dismissals in Spain, standardization of compensation for unfair dismissals in Italy), they quickly met with opposition from part of the public. The aim of these measures was to give greater visibility to micro-enterprises and SMEs (which will also benefit from a public service providing access to legal advice) on the conditions for economic redundancies by clarifying the criteria and regulating compensation in cases of abuse in order to stimulate hiring on permanent contracts. As the text currently stands, the criteria for economic redundancies are adjusted (decline in orders or turnover, from one to four consecutive quarters depending on the size of the company), the scope of their assessment is not national, and the scale has been maintained for information purposes only.

By reshaping the conditions for dismissing employees on permanent contracts, the government hopes that this will allow a larger proportion of the working population to have access to them. The dualism of the labor market in France concentrates precariousness on certain categories of employees who find it difficult to escape (low-skilled, young people).

Finally, the personal activity account, which is scheduled to come into force on January 1, 2017, is the main tool for securing career paths. The least skilled employees (particularly in smaller companies) have less access to training and are over-represented in the unemployed population. However, the details of this account remain unclear. While all social and social protection rights could eventually be integrated into the CPA, the main focus at the moment is on training rights and the hardship account, while the question of the fungibility of these rights does not seem to have been decided.

In addition to these three areas of reform, the labor law also includes elements that are less structural for the functioning of the labor market: for young people, particularly those who are not in training, employment, or education, enhanced support and an allowance are planned; company-level negotiations on the right to disconnect from 2017 onwards; extended protection against dismissal on return from maternity leave, etc.

Under these conditions, the proposed labor market reform in France still appears unbalanced. While the measures envisaged to help companies adjust to their economic environment are very significant, the concessions granted to employees are limited for the time being and are based primarily on the hope that the labor law will boost employment.

2. A difficult macroeconomic context

At the European level, numerous labor market reforms have been carried out in recent years. The recent economic upturn in the eurozone has provided an opportunity for supporters of the labor law to highlight the beneficial effects of these reforms among our European partners, while its opponents see it primarily as the result of low interest rates, the euro exchange rate, oil prices, and the easing of budgetary constraints.

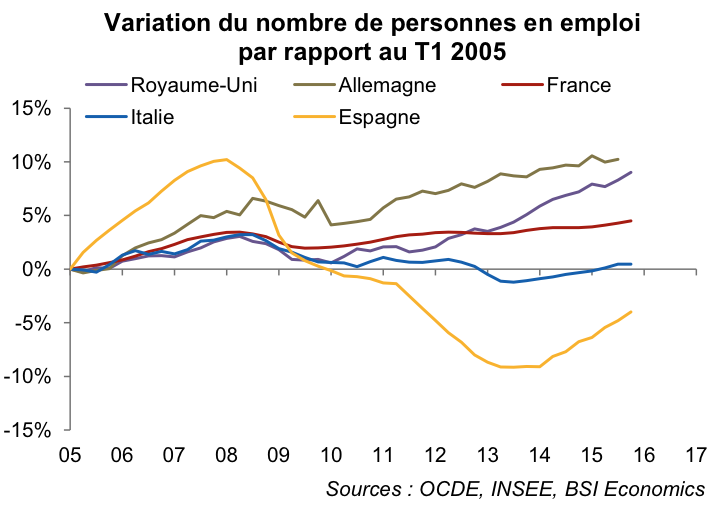

It is clear that unemployment is falling in all the major European economies (Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, Germany, and the Netherlands)… with the notable exception of France. While this trend is rather worrying, France’s situation is not catastrophic compared to that of its neighbors. In Spain and Italy, the unemployment rate is falling but remains higher than in France, while the United Kingdom, Germany, and the Netherlands already had lower unemployment rates before the crisis.

In terms of economic activity, France is not lagging behind. Over the period 2007-2015, the French economy proved resilient, growing 3% above its Q1 2008 level in Q4 2015, compared with -0.1% for the eurozone. Over the last two years, France has certainly recorded lower growth than the eurozone, but this only partly explains its persistently high unemployment rate. Labor market adjustment mechanisms are specific to each economy (number of hours worked per person, productivity, number of jobs), and the recovery in growth is currently less job-rich in France.

On a macroeconomic level, the combination of favorable factors (low interest rates, gradual decline in the exchange rate, low oil prices) is providing undeniable support for growth, while the management of aggregate demand is now clearly identified as the main obstacle to accelerating growth in the short term in Europe, particularly in the eurozone. In France, economic policy efforts have focused on restoring corporate margins (CICE, responsibility pact, accelerated depreciation measures) in response to the distortion in the distribution of added value. This distortion led to a critical weakening of corporate profitability in certain sectors during the first phase of the crisis. Conversely, wages (and household disposable income) had held up relatively better.

In a context of public deficit reduction, the financing of this business support strategy is partly at the expense of households (tax increases) and local authorities (reductions in grants to local authorities), whose investment spending is declining. This weakening of demand is currently weighing on the short-term recovery.

In this regard, further destabilization of private demand poses a real threat to the French economy. While French economic growth barely exceeded 1% in 2015 and expectations remain moderate for 2016 (the IMF and the government forecast 1.5%), inflation also remains very low. Under these conditions, a downward adjustment in employment (and wages) in the wake of labor market flexibility reforms would pose a threat to economic activity in the short term. The quest to increase potential output growth is taking place at a time when the whole of Europe (with the exception of Germany) is operating below its potential output level.

3. An effective response to labor market dualism?

On a more structural level, there is no consensus on the effects of the main measures aimed at making the labor market more fluid. On the one hand, supporters of the labor law believe that removing the protection of permanent contracts will benefit the least qualified, who are most affected by job insecurity. On the other hand, its opponents argue that job protection does not have a long-term impact on employment levels, but rather on its role in relation to the economic cycle (a negative shock to the economy causes a more brutal adjustment in employment if the labor market is less regulated).

The labor law is intended to be a tool for reducing the dualism of the labor market in France. Some of the workforce (young, low-skilled workers) suffer from this fragmentation and serve as an adjustment variable, stuck in a situation of precariousness. On the other hand, employees on permanent contracts with a high level of skills are in a more secure situation.

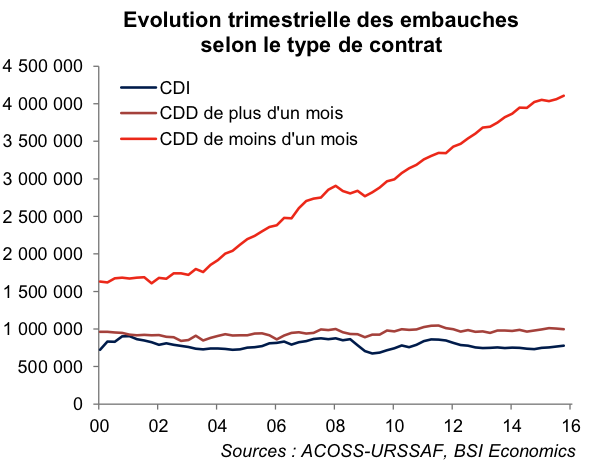

However, in view of recent developments in the labor market, it is not clear that reducing the level of protection for employees on permanent contracts will enable more people to benefit from them. Over the period 2000-2015, the share of permanent and fixed-term contracts in employment remained fairly stable. On the other hand, the number of fixed-term contracts of more than one month compared to the number of permanent contracts has fallen slightly, while the number of fixed-term contracts of less than one month has risen sharply (partly due to the reduction in their duration). The median duration of a fixed-term contract is just over one week. This is particularly true in companies with fewer than 20 employees.

Based on this observation, we may wonder whether the labor law is actually suited to the objective of promoting the sustainable integration of the « most vulnerable » into the labor market. The main changes in fixed-term contracts (number, duration) have taken place in the segment of very short contracts, which seem to have very little potential for conversion into permanent contracts. Similarly, the (abandoned) proposal to impose a surtax on fixed-term contracts would probably not have led to better access to permanent contracts for the most precarious workers, and would have run counter to the government’s policy of reducing labor costs, which has been in place for several years and most recently resulted in the announcement in January 2016 of the small business/SME hiring scheme.

Improving access to training in order to give all employees the skills they need for long-term integration therefore seems to be the best response to the dualism of the labor market. For the moment, however, this aspect seems to be the least advanced part of the labor law.

Beyond its potential economic effectiveness, the labor law appears to be an eminently political choice, which is not the subject of this commentary. The introduction of a scale (even an indicative one) for unfair dismissals can only depend on its effectiveness in stimulating hiring in microbusinesses and SMEs. Similarly, changes to the conditions for dismissing employees on permanent contracts cannot depend solely on their ability to reduce the dualism of the labor market.

Conclusion

The economic policy pursued by the government over the past several years has made it possible to rebuild corporate margins, with investment spending picking up over the past several quarters, by lowering labor costs. The El Khomri law, by tackling labor flexibility this time around, aims to give companies the ability to adjust quickly in terms of employment, and at a more predictable cost, to their economic environment in order to remove barriers to hiring.

While the CICE tax credit and the responsibility pact are ramping up and have been partly financed by a drain on household and public demand, France remains vulnerable to a new shock in the short term from an unbalanced reform, while its gains in potential growth remain uncertain.